Not long after editor Terilyn A. Shropshire finished work on the massive adventure film “The Woman King,” she found herself at an orientation meeting for Academy GOLD, a talent inclusion initiative for which Shropshire serves as a mentor, alongside director Lee Isaac Chung (“Minari”). “I asked him what he was up to, and he said, ‘I’m in preproduction on this film called ‘Twister,’” Shropshire told IndieWire. “At least that’s what I heard. And I said, ‘Twister Twister?’”

Chung told Shropshire that the movie was not a sequel to the 1996 disaster movie but a “revisit.” He also told her it was fortuitous that they were meeting. “He said, ‘My editor Harry Yoon isn’t available to work with me this time, and you’re one of the people he recommended I meet,’” Shropshire said. “About a week later he sent me the script and we had a meeting. We met for coffee for two hours, and at the end of that, he said, ‘I’d really like to work with you on this,’ and we got started — and it’s just been the most incredible experience.”

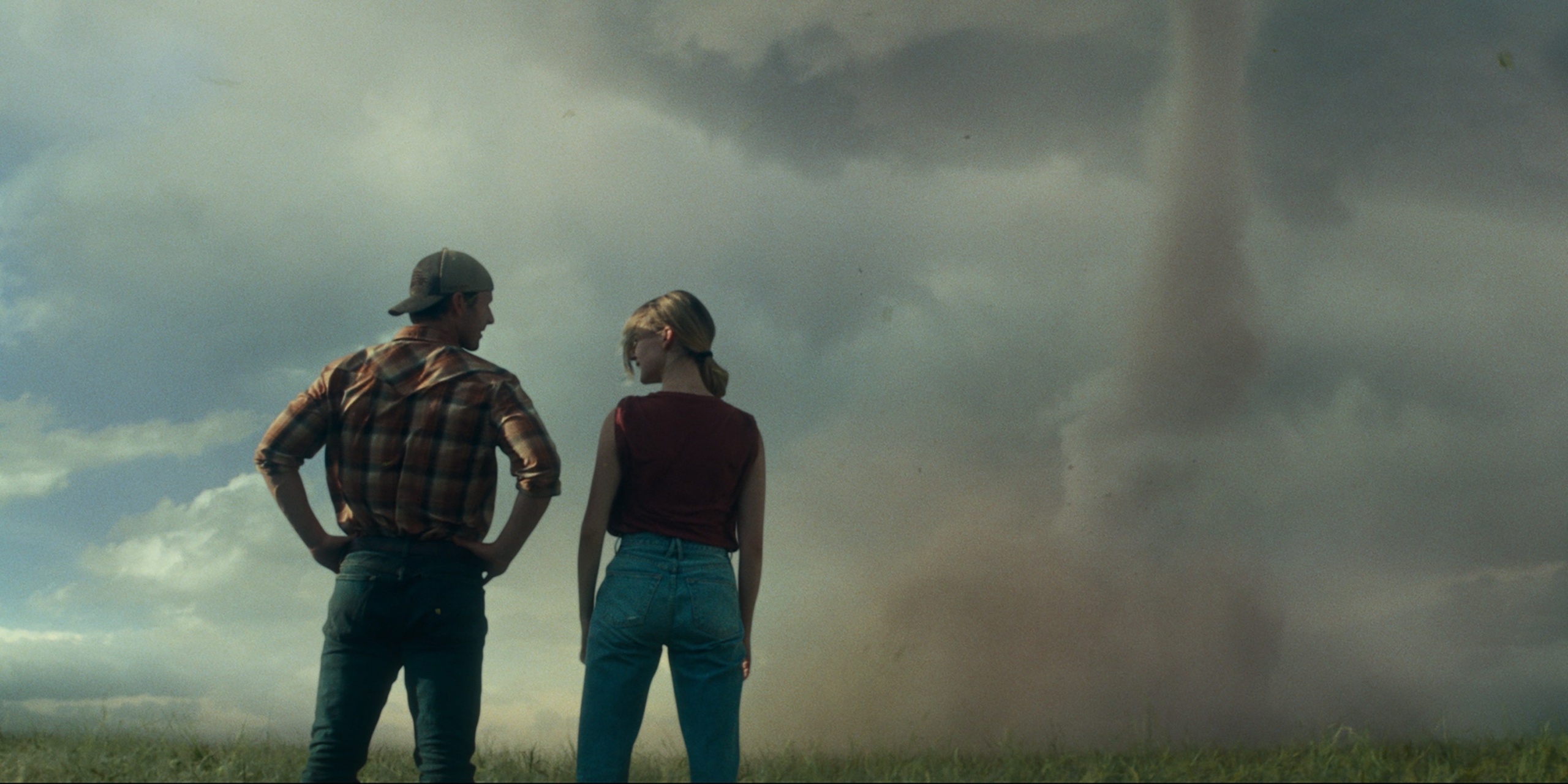

It’s an incredible experience for the audience as well, as “Twisters” takes Chung’s well-established talent for using landscape to define and deepen character and applies it to a crowd-pleasing adventure story, resulting in one of the most thrilling and emotionally satisfying summer blockbusters in years. For Shropshire, one of the challenges was to create a sense of non-stop action without letting the rhythm become monotonous. “It’s all about modulation,” Shropshire said, adding that the key was to use each tornado sequence to convey something about the characters and how their experiences reflected one of the movie’s key themes: fear.

“We had to make the audience feel that they were taking this emotional immersive journey with the characters,” Shropshire said. To that end, she and Chung agreed that each tornado should have its own personality — both to differentiate between each set pieces and to give each action sequence its own specific purpose in the narrative. “Each tornado is a character, and we wanted them to have as much distinction as the human characters.” According to Chung, the visual effects team based each set piece on a real-life tornado. “My favorite thing from the VFX side is that at the end of production, they gave me a video for every tornado,” the director told IndieWire. “It’s like a police lineup, and they’re spinning, and you can see that they’re all individually unique.”

One of the biggest challenges for Shropshire was figuring out how long to let the movie breathe in between the tornadoes; she knew the spectacle would be the main draw for audiences, but she also knew that too much action without relief could become numbing. “You want to give the audience moments to process because often when I watch a film that’s only moments of intensity, I don’t feel anything at the end.” Shropshire was careful, therefore, to give sequences like a New York-set passage (after the movie’s terrifying opening tornado) the time for the characters to imprint on the viewer. That said, she never wanted to linger on the low-key dramatic scenes. “You have to remove things and not sit on them too long, because you don’t want the audience to get impatient and say, ‘When’s the next tornado?’ It was very tricky.”

Editing a summer tentpole came naturally to Shropshire as someone who always tries to put herself in the viewer’s shoes and maintain that perspective throughout the postproduction process. “You always have to forget what you know and be an audience for your film,” she said. “You have to go in and be very surgical but then be able to step out and look at it and feel it, and that’s just the natural process.” In the case of “Twisters,” that process was complicated by the fact that Shropshire was often cutting without completed visual effects — or even basic footage because the movie shut down during the SAG-AFTRA strike.

“Two and a half weeks before we finished shooting, there was a strike,” Shropshire said. “At the time Universal was not moving the release date, so we had to work with what he had, which was often storyboards and pre-viz. It was like this little patchwork.” In order for the visual effects department to meet its deadline, Shropshire and Chung had to begin turning over shots quickly, making their best guess at how everything would work in the overall rhythm without key scenes having been shot. “We built what we had and created a template for what we didn’t with the understanding that at some point we would go back and finish the film.”

Chung often resorted to unorthodox methods to fill in the missing footage. “I had moments where I filmed some of our editing people and my associate producer Doug in my car,” Chung said, “pushing buttons and stuff like that to get these shots because we hadn’t filmed all of the inserts.” Shropshire said that the heavy visual effects orientation of the piece made it different from other films she had edited. “It changes the idea of how to balance the work, because there is this machine you need to feed when you have a release date and over a thousand visual effects that have to be delivered,” she said.

As the effects came in, Shropshire adjusted the timing of each scene to expand or contract depending on how the completed shots affected the overall emotional impact; she also credited the sound team at Skywalker with making the tornadoes truly come to life. “We had them on from the beginning, and they really started to dig into the characters of each of these tornadoes,” she said, with Chung adding that the sounds were not just based on research but personal memories. “[Supervising sound editor] Al Nelson survived a tornado when he was 9 years old,” Chung said. “He was trying to mine that memory and get some of the pieces he remembered into the tornado.”

Once the strike was over Chung and Shropshire were relieved to finally begin working with all of the necessary footage. “I was so glad to start replacing those shots as we were filming,” Chung said. In the later stages of cutting, Shropshire watched various versions of the film with friends and family to get a sense of what was working and what wasn’t. “You start to bring people in very early who you trust who can give you constructive feedback,” Shropshire said, though she said the verbal feedback is less important than just sensing how a movie is playing in a room. “There’s nothing more telling than sitting there and feeling the body language — it could be three people in the room or 200 people in the room.”

Throughout the process, Shropshire never lost sight of a key guiding principle, no matter how buried she got in action and visual effects shots: “Lee Isaac Chung is very character and story driven, and that’s what we really wanted to work on — to build a foundation with humanity within all the spectacle.”