Director Jeff Zimbalist did a little of what’s called rooftopping in his teens and 20s, finding ways onto the tops of buildings and bridges and construction cranes that loom above city skylines.

In 2015, the Instagram algorithm served Zimbalist something that combined that early passion for urban exploration with his work as a filmmaker: He became fascinated by the way Russian rooftopper Angela Nikolau would turn feats of high-stakes trespassing into artistic imagery and short-form videos that felt much more like performance art.

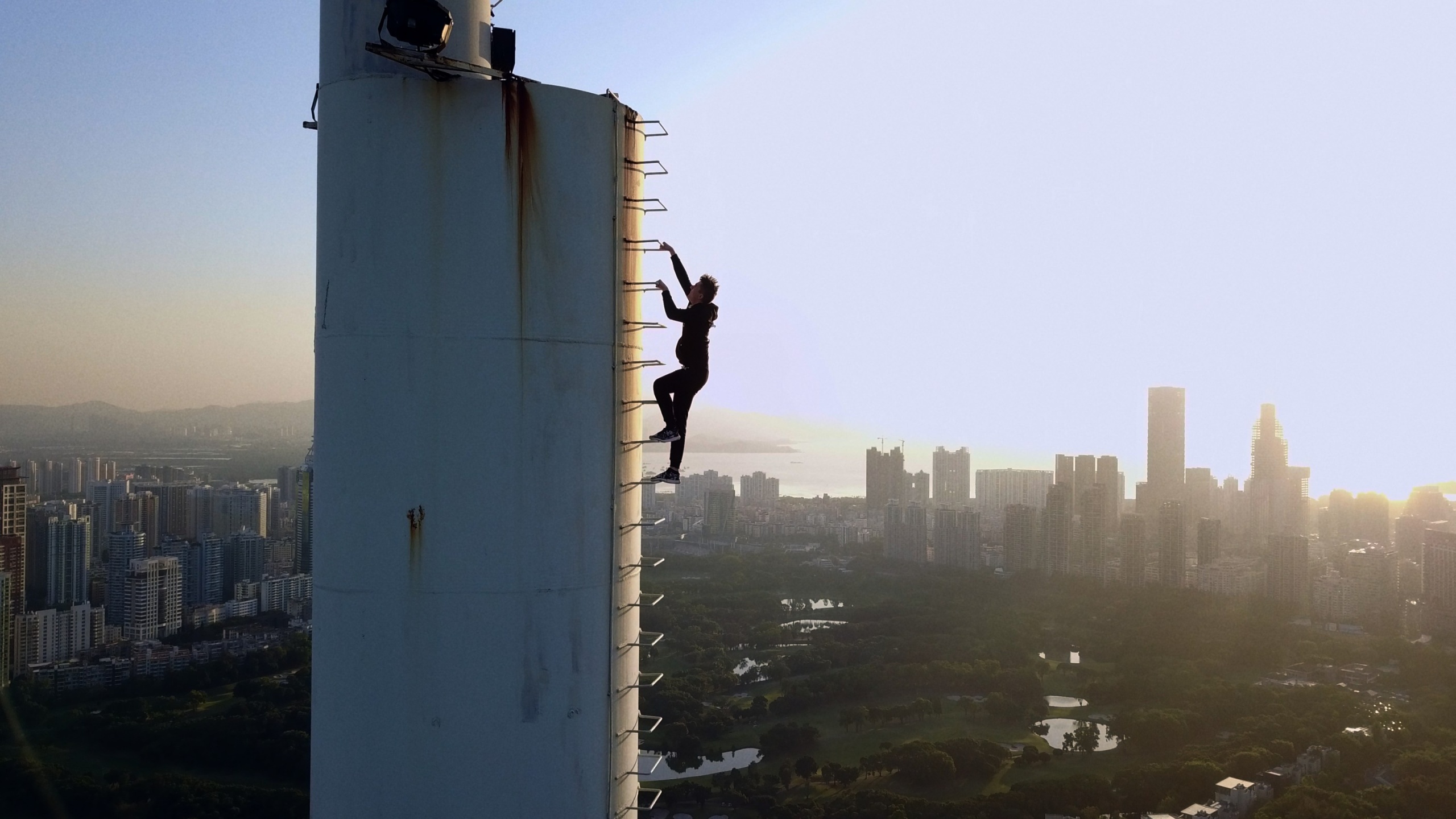

However, the documentary he set out to make about her and her rival/colleague Ivan Berkus, changed shape over the seven years of making it and required a specialized process to create imagery as immersive as the experience of rooftopping itself. As the name “Skywalkers: A Love Story” implies, the film co-directed by Zimbalist and Maria Bukhonina became about Berkus’ and Nikolau’s romantic relationship. Intimacy, it argues persuasively, is as big a challenge as climbing to the top of a skyscraper.

A key test for the film’s crew, however, was in integrating footage from across different camera types into a film that would look as immense and feel as immersive as the buildings Berkus and Nikolau climbed.

Zimbalist and Burkhonia tried to keep the same lens package on the cameras they shot with (first a Canon C-300 Mark II, then a Mark III, then a C-500) but were always conscious of adding in different grain structures to achieve a consistent visual look.

“We did use a lot of cinema grain to try and even out the look. So sometimes that meant degrading some of the sharper imagery in order to better match some of the less sharp imagery around it,” Zimbalist told IndieWire.

Shooting dramatic or introspective or even just preparatory scenes of Nikolau and Berkus training on the ground had the advantage of being done on the same two cameras with the same two lenses. The real challenge for the “Skywalkers: A Love Story” filmmakers, like their subjects, were the extreme climbs themselves. Zimbalist told IndieWire that they had to streamline all the gear Angela and Ivan would take with them on a climb, which included everything from selfie-stick footage and different iPhone cameras to GoPros and law-enforcement-grade night vision cameras. “There was a lot of matching in post,” Zimbalist said.

But the level of film grain, especially with the night vision cameras shooting in total darkness, was something Zimbalist and the filmmaking team leaned on to create a visceral sense of trespassing in a forbidden space. “That grit adds to the authenticity, and you’ve got to embrace it for what it is and not pretend it’s something else,” Zimbalist said.

Leaning unapologetically into where the images were coming from, even if that was lower resolution cameras, did not make the film feel smaller. “Getting into the color room and the conform room and seeing [the images] on a bigger screen in full res was actually quite fun because it was reassuring. I was like, ‘Yeah, my God, this stuff actually blows up. It works.’ And then, of course, we did that to [fit the film on] IMAX, and it continued to work,” Zimbalist said.

Zimbalist and the filmmaking team wanted to make sure the audience would, as much as possible, feel present with Ivan and Angela on their climbs, which meant being very deliberate about introducing the different kinds of views we get of them, and then creating a smooth rhythm of cutting between options. Once “Skywalkers: A Love Story” sets down its visual language for the climbing sequences, it starts being able to mix and match more freely — although drone shots of the building exteriors/skylines that Nikolau and Berkus are traversing provide necessary visual context, and never let us look too long at images with a lot of sensor noise.

However, for the biggest climb in the film, the Malaysian mega-tall skyscraper Merdeka 118, the filmmaking team couldn’t get a drone high enough from the ground, so they needed to find another building from which to launch.

“We had to do rooftopping just to get to a roof high enough from which to send our drone, and then once we were able to find the right roof, our operator was able to get that incredible swooping, diving footage that makes you feel, in this first-person point-of-view, like you’re falling down the side of the building,” Zimbalist said. “That was high-risk stuff for him to do. So he’s not credited in the movie — and he asked for it to be that way.”

The most crucial drone work on Merdeka, however, was done by Berkus, with Nikolau really paying attention to the coverage that makes the scenes of them ascending the skyscraper and everything that happens inside so electric.

“[Nikolau] started to understand needing different angles and would set the camera up for a wide and then put it on a GoPro stick and get reverse shots of them talking. So it ended up being quite the collaboration,” Zimbalist said.

None of that collaboration would’ve seen the light of day, probably, if Nikolau and Berkus had been caught climbing the Merdeka. So Berkus taped their memory cards to his drone and flew it down to where the filmmakers were waiting on an adjacent rooftop.

“I was really nervous they’d go to all that effort, get this amazing stuff, and then there’d be a mishap on the way down. Often I was the Nervous Nelly, and they were more confident, cool cucumbers,” Zimbalist said. “But I play out every worst-case scenario and try to create precautionary measures for each of them.”

Zimbalist’s catastrophizing paid off in a film that synthesizes different looks, from the grainiest low-resolution to the most sweeping and cinematic, into a romantic relationship. And like any good romance, its twists surprised even the filmmakers who had set up core themes and ideas as part of the structure they’re exploring.

Nikolau talks in the film about the relationship between “flyers” and “catchers” in a trapeze act, and how ready she is or isn’t to accept a more grounding, potentially limiting force in her life. But over the course of the Merdeka climb, as Zimbalist told IndieWire, Berkus and Nikolau captured footage of each other switching between roles, with one pushing forward and the other grounding and calming.

“It’s through that switching of roles that they accomplish their life’s biggest challenge. And I found that was a profound insight into relationships — that we all need inner balance, that we sometimes need to be the rock and sometimes we need to be the star,” Zimbalist said. “I love that I’m surprised when I think I’ve got a handle on the theme of a movie, that takes it one step further, and I look at the new revelation and go, ‘Yeah, that’s actually more profound.’”

“Skywalkers: A Love Story” is available to stream on Netflix.