In a recent interview with IndieWire, master of suspense M. Night Shyamalan admitted to not having seen French filmmaker Robert Bresson’s WWII prison thriller “A Man Escaped” until his daughter, Ishana Night Shyamalan, suggested it to him.

“I remember how profoundly, when Ishana told me to watch that, it affected me,” Shyamalan said of the film. When told that his most recent film, the concert-set “Trap,” may be his version of “A Man Escaped,” Shyamalan also said, “Probably, by the way. That’s so funny you say that. Probably.”

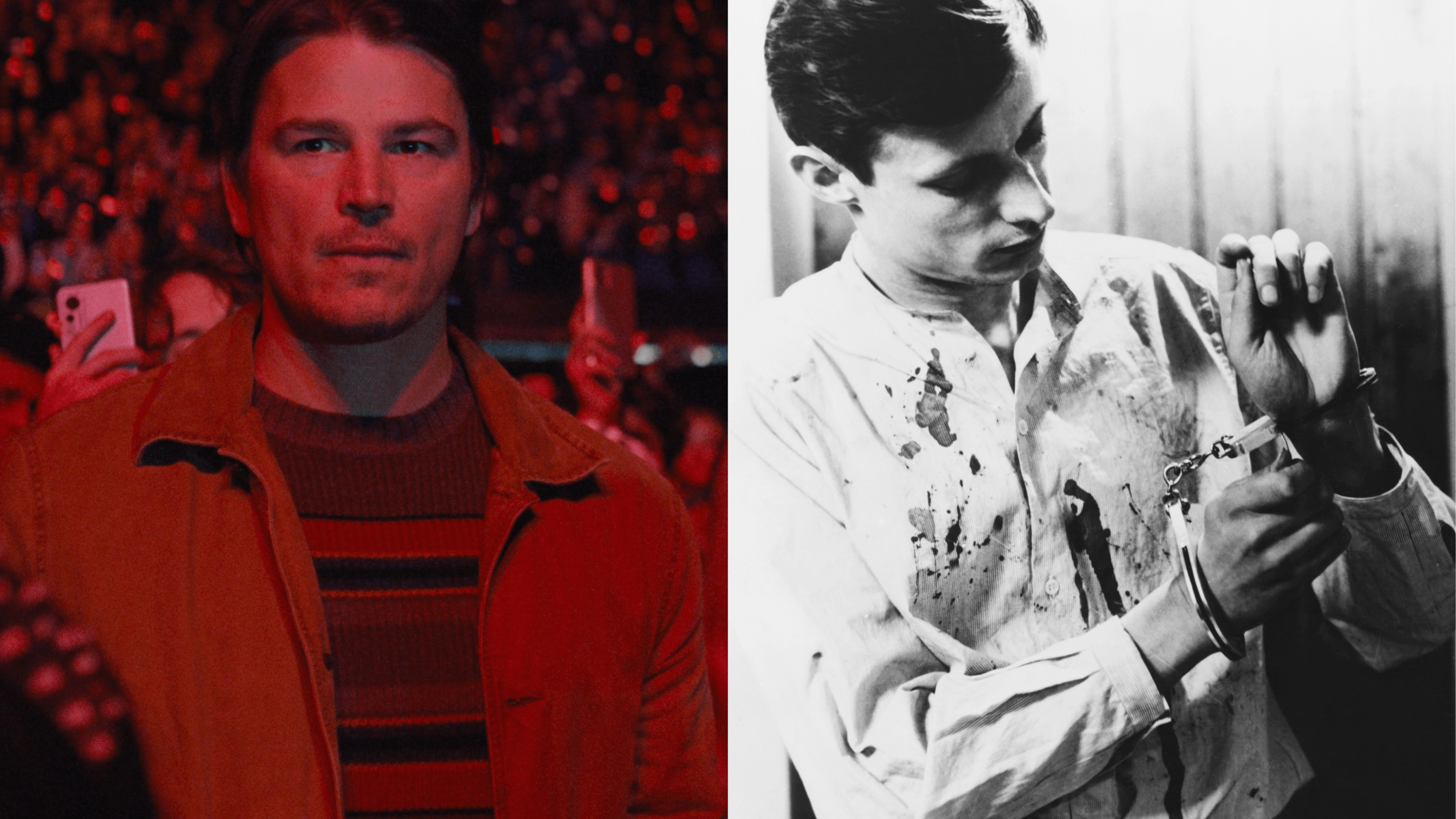

So how do the two confined-space thrillers stand against one another? Let’s break it down starting with “Trap.” Starring Josh Hartnett as girl-dad Cooper, who escorts his pre-teen daughter to a pop concert for her favorite superstar, Lady Raven (Saleka Night Shyamalan), the film quickly becomes a cat-and-mouse game as it’s revealed that Cooper is actually a serial killer known as “The Butcher” and a trap has been set for his capture. Local police and FBI have surrounded the concert venue, blocking every possible exit and combing the entire stadium for all attendees who match the description they have.

For those who believe attending Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour would be a prison sentence, this is the movie for you. Immediately upon entering the venue, Cooper starts to notice the heightened security presence and, turning on the charm for one of the stadium’s employees, discovers that they’re there for him. As the walls start to close in, Cooper is quick to push back, scoping out possible escape routes and building a strategy for him and his daughter getting out without having her suspect something is wrong. Tension is a staple of Shyamalan’s oeuvre, but never before has he crafted something so objectively hilarious. Hartnett’s performance as a dangerous animal pushed into a corner and forced to balance his baser instincts with the mask he’s built is as cleverly silly as it is terrifying, especially the more complicated his schemes get.

“A Man Escaped” is a different beast entirely. François Leterrier — for cinephiles out there, that’s the father of Louis Leterrier, director of “Transporter” and “Now You See Me” — plays French Resistance fighter Fontaine, based on the real-life soldier André Devigny whose memoir the film inspired. We meet Fontaine as he’s being transported to Montluc prison during the height of WWII and as part of our introduction, he’s seen carefully plotting his escape from the car driving him to his dark fate. This is a man who can’t be held down. Strategy and patience are important to him, but opportunity always takes precedence. Though his run from the car only lasts a few seconds before he’s once again apprehended, we somehow know Fontaine won’t be kept locked-up for long.

Once placed within the prison’s walls, Fontaine looks past the cruelty of his situation to study the details of his surroundings with careful precision. Bresson accentuates these observations with close-ups and tight editing, constantly feeding viewers new information as it comes to Fontaine and never wasting a shot. Similarly, with “Trap,” Shyamalan and DP Sayombhu Mukdeeprom (“Challengers,” “Grand Tour”) play with framing and blocking to emphasize Cooper’s perspective as he weaves throughout the stadium that’s become his prison, using every trick in his book while at the same time, flying by the seat of his pants. Uncertainty is a key factor in the suspense of both films. Uncertainty within the audience and within the characters they’re presented with. Can these men pull off the feats they’re attempting?

Despite Cooper being presented as a monster, his closest cinematic comparison being Norman Bates of “Psycho,” we also register him as a goofy family man trying his best to make a good person out of his daughter. Or is all of that just cover? Part of the charm of “Trap” is its slyness. Should we be rooting for this brutal kidnapper and murderer whose M.O. involves leaving his victims’ bodies out in neatly organized pieces? I’m sure Shyamalan would say, why not? It helps that we never see Cooper go full “Butcher” and kill someone, but no matter the harm he does unto others, including scarring a young food service worker with oil burns, or the lies he tells to achieve his objectives, we as an audience can’t help but be drawn to watching how far he can go, perhaps a part of us even wanting him to go further.

By comparison, Fontaine is almost a saint-like figure. With each new prisoner he comes across, he finds a new reason to move forward and break free, thereby allowing him to help the Resistance further and perhaps even liberate his comrades. His work is slow and painstaking, but time is not on his side as he knows sooner or later, his execution is bound to come. It is only through the help and trust of a younger prisoner called Jost that François actually sees a possibility of making it out. This draws another link back to “Trap” in that for all Cooper does to shield his daughter from the truth of who he is, it is her fandom of Lady Raven that he ultimately abuses in order to get clear of the SWAT Team working to apprehend him. In this way, it is youth’s pureness and hope for a better future that pushes both central figures forward, negatively in the case of “Trap,” but positively for “A Man Escaped.”

But what’s the message underneath both of these craft-focused explorations of perseverance in the face of tremendous adversity? For “Trap,” the narrative feels inexorably tied to Shyamalan exploring who he is as a father, an artist, and, most importantly, a human being. At its core, “Trap” is perhaps best viewed as a dissection of parenthood and, to reference another Shyamalan film, the split we create within ourselves to protect those we love from whatever darkness we have inside ourselves. The inclusion of Night’s own daughter, Saleeka, as the centerpiece of the concert Cooper is trapped at, makes one wonder how deep the layers go. Taking it a step further, the film almost acts as a conclusion to an unofficial trilogy regarding legacy, with “Old” and “Knock at the Cabin” setting up the lack of control we have in bringing others into this world and “Trap” paying it off by reminding us all we can do is move forward, come hell or high water or thousands of volts of electricity coursing through your body.

In taking on Devigny’s memoir only a decade following the war, a time in France marred by conflicts in Vietnam and Algeria, as well as disillusion on the homefront, Bresson is speaking to a nation desperate to free themselves from the shackles of violence and authoritarianism. A celebration of the determination put forth by the Resistance, as well as an exquisitely composed entertainment piece, “A Man Escaped” also served to remind audiences, French and otherwise, that we are only as oppressed as we allow ourselves to be. In a sense, both Bresson and Shyamalan’s goals with their films and characters is to reflect issues that feel simultaneously personal and universal, but while Bresson chooses to do so with intricacy and nuance, Shyamalan goes full sicko mode, tapping into our tortured psyches with reverent glee and a bumpin’ beat.