At the Sundance 2024 world premiere of “Sugarcane” at The Library in Park City, the crowd jumped to their feet for a standing ovation; rookie director Julian Brave NoiseCat and Canadian filmmaker Emily Kassie thanked the participants on hand from British Columbia’s Williams Lake First Nation.

NoiseCat’s father, Ed Archie NoiseCat, became part of the story. And he was there at Sundance, along with tireless investigator Charlene Belleau, who was tracking evidence, uncovered in 2021, of unmarked graves on the grounds of an Indian residential school run by the Catholic Church in Canada. The filmmakers embedded themselves in the community to try and break the pattern of silence around the forced separation, assimilation, and abuse many children experienced at these segregated boarding schools. What they uncovered was shocking.

The film won the Sundance U.S. Directing Award for Documentary, and later collected more awards at a string of festivals. And NatGeo‘s doc head Carolyn Bernstein scooped up the film at Sundance with hopes it might play to the Academy documentary branch. It opens in limited release on Friday, August 9.

When Kassie, whose background is in investigative journalism, heard about the unmarked graves, she felt compelled to look further. “I’ve covered stories all over the world and focused on human rights abuses and mass atrocities everywhere from Afghanistan to Rwanda,” she said at a recent Neuehouse screening in Hollywood. “I am also Canadian, and I had never turned my lens on my own country and the atrocities that it committed against its First People. So when the news of potential unmarked graves broke in May of 2021, I felt gut-pulled to tell the story.”

The first thing she did was text her old Huffington Post colleague Julian Brave NoiseCat. They had been trying to collaborate for years. As she waited for him to get back to her, she came across an article in the Williams Lake Tribune, and emailed Williams Lake First Nation Chief Willie Sellars, who told her they had been wanting someone to chronicle their own investigation. When NoiseCat called her back, he was interested in collaborating.

“She told me that she identified a First Nation that was needing a search,” NoiseCat said. “And that search was happening at St. Joseph’s Mission.” He paused and told her that was the school where his father was born. “Out of 139 Indian residential schools in Canada, the filmmaker who I happened to be seated next to at my first reporting job happened to make her first documentary about Indian residential schools and had chosen that school.”

For the first year of the three-year, 160-day shoot, NoiseCat was behind the camera with Kassie. But it soon became clear that he and his father were part of the story. “The reason why I was hesitant to work on a documentary about any residential schools in the first place was that I knew that my family had a painful connection to the residential schools,” he said. “I didn’t know what that story was. I didn’t know whether I could touch that subject matter in a new medium that I had never done before, and I didn’t know if I could go there with my own story. That was not the intention. I lived with my dad for two years during the making of the film, and he asked a lot of questions and clearly wanted answers.”

What also pushed NoiseCat over the edge was watching Williams Lake Chief Rick Gilbert, who died in September 2023, go to the Vatican. “He was sharing something that had haunted him about his own DNA for his entire life,” he said. “And I ultimately felt that if Rick as an elder, was willing to get on a plane to go confront a representative of the Catholic order that abused him and that that abuse had resulted in his birth, and here I was, the child of the only known survivor of that incinerator that was at the center of a story of infanticide at St. Joseph’s Mission, if I was not willing to go there with my story, then I wasn’t giving this story my all.”

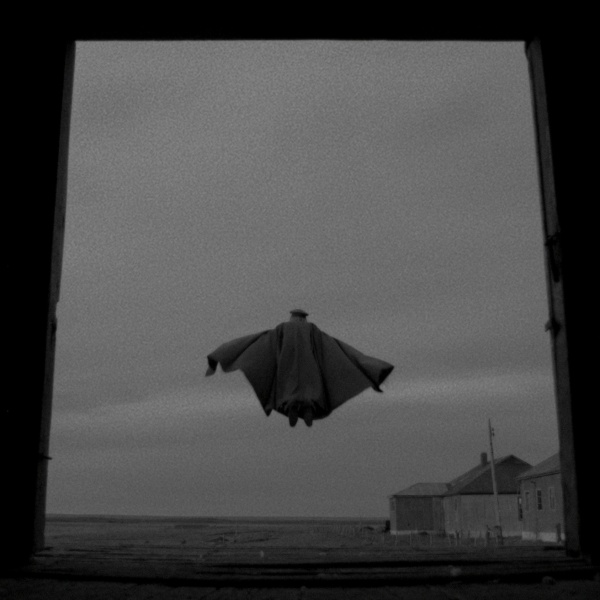

It was tough to get some of the folks to open up about what happened at St. Joseph’s. NoiseCat’s grandmother could not talk about it. So many priests abused young men and women, who gave birth to children who were often thrown in an incinerator. “The silences sometimes speak more than what people have to share,” said Kassie. “The truth about the school is that it was so painful and so awful that it wasn’t just that people were speaking and were not heard. They stopped speaking, and those truths became buried within themselves. The film started as an excavation below the ground, but what ended up happening was an excavation well above it, in the minds and recesses of memory of our protagonists.”

The filmmakers built trust and pulled some revelations from the community over time. “Creating the space for people, and allowing the camera to be something that gave people agency, that said, ‘You matter and your voice matters and we want to hear from you,’” said Kassie, “Julian would say something to me, like, ‘This is a community living on the edge of death.’ Well, what does that mean? What it means is that Jules went to 10 funerals during the making of this film, and I attended several myself, because this is a world that is still reckoning with the ramifications of the residential schools addiction and suicide and abuse.”

Excavation of the unmarked graves is still to come. “We actually uncovered something much darker and much worse,” said Kassie, “that children were being born at the school to priests, some of them, and they were either being forcibly aborted, forcibly adopted by white families, and in some cases, incinerated, and that has not been reported yet. ‘Sugarcane’ is the first reporting of that fact, and these are stories we’ve heard at many other schools. We don’t think that this was an isolated incident.”

“We happened to be called to the story at the moment when that silence was finally broken,” said NoiseCat, “when the spell was finally broken, when the spirits of the deceased came back to the life of our community.”

“Sugarcane” opens in theaters from National Geographic Documentary Films on Friday, August 9.