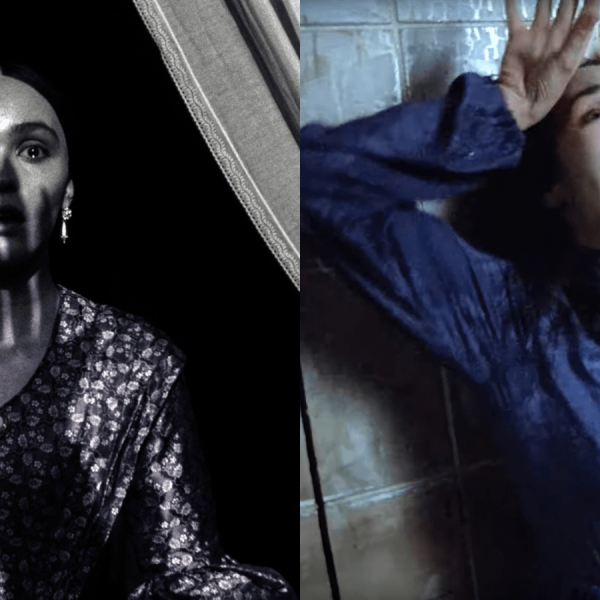

“Skincare,” the sly thriller starring Elizabeth Banks now in theaters, begins with an eerily stressful makeup routine performed by Banks’ celebrity aesthetician character, Hope. From there, the movie acquires what cinematographer Christopher Ripley called an “unhinged momentum.”

That translated to the actual filming, as well, which took all of 18 days in Hollywood. Not bad for a film that’s set in 2013, which required a surprising amount of retro equipment to pull off.

“[Director Austin Peters] and I both were very interested in that time period, a period in flux with a lot of changed energy,” Ripley told IndieWire. “Hollywood was, as Austin described it, ‘fully torqued.’ Uncanny and very disturbing, intense energy going on.”

That energy was the perfect backdrop for the increasingly unraveling Hope, whose shot at financial security and fame with her own product line is upended when a rival aesthetician moves in across from her salon, and a wave of harassment begins.

What Ripley described as the “insidious undertones” of the cinematography only enhanced the shooting location: Crossroads of the World in Hollywood, an open-air mall that once served as home to filmmakers’ offices (including Alfred Hitchcock) but one that also has an insidious past of its own. Specifically, Ella Crawford had the mall built in 1936 on the site of her husband’s fatal shooting, a man who also served as inspiration for some of Raymond Chandler’s criminals (proving his Los Angeles bona fides).

That meta layer adds to the unease, but Crossroads of the World served a more practical purpose. “Skincare” needed a shooting location with two offices facing one another so that Hope would constantly be confronted by her new, rising rival, Angel. “We didn’t want it to be filmed on a soundstage and cut to location, and you’re stitching it together,” Ripley said. “You feel the other space oppressively looming. We even kinda had it that the pink neon glow [of Angel’s sign] is leaking into the window of her space and reflecting on her eyes. Just this idea that this oppressive energy is coming from the other space.”

The lighting gradually ratchets up that oppressive feeling, including the reconstruction of those orange-tinged streetlights that have been phased out in favor of white LEDs. Ripley and his team painstakingly recreated them, correctly clocking that only sodium-vapor gas discharge lights could truly capture the look of the era’s nights.

“We’d place these practical fixtures in L.A. and rig them onto buildings,” Ripley said, “so the fixtures could be visible in the frame and be period accurate. A sheen of something weird on top of this glamorous Hollywood world. You can emulate that look, but the actual fixtures [and light] deadens the [skin] in a certain way and does these horrible, oppressive things.”

Equally oppressive (but for the filmmakers) was a key motel room location where the audience learns more about who is behind Hope’s torments. Available for just a day, Ripley and his gaffer, Mathias Peralta, used their own bulbs in the room’s fixtures to allow Peters 360-degree filming. The scene includes some aggressive, Travis Bickle-esque choreography, which camera operator George Bianchini got very into.

“He gets into the character, so he was almost acting with the camera and it was this insanely heightened sleazy moment, with me and Austin sitting on a toilet seat in the bathroom looking at a tiny monitor,” Ripley said. “It was the only place we could be. So there we were, going crazy on Day 4, saying, ‘I think we have something here.’”