From their feature film debut with the exquisite India-set drama “The Householder” in 1963 to their final collaboration on 2005’s sumptuous historical epic “The White Countess,” director James Ivory and producer Ismail Merchant were cinema’s most reliable director-producer team, a couple (in both work and life) responsible for a filmmaking streak that consisted of dozens of great movies and no bad or indifferent ones. Noteworthy for their supreme attention to visual detail, highly literate screenplays (often written by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala), and flawlessly cast ensembles, the films of Merchant Ivory Productions were near-annual gifts that were often undervalued; unlike less prolific auteurs like Stanley Kubrick, Ivory never made us wait for his movies, which made it easier to take them for granted.

Not that Merchant Ivory Productions lacked box office success or acclaim in their time; “A Room with a View” (1985) was a bona fide smash that won three Academy Awards and gave the company newfound leverage after over 20 years in the business, and “Howard’s End” (1992) and “Remains of the Day” (1993) were even bigger hits. Yet for every Merchant Ivory release that connected with the critics and filmgoing public there were many others such as “Slaves of New York” (1989) or “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries” (1998) that failed to resonate regardless of their considerable strengths. For Merchant Ivory enthusiasts, the lack of widespread appreciation for the filmography in all its breadth and depth has always been more than a little frustrating.

Thankfully, filmmaker Stephen Soucy has now addressed the need for a comprehensive celebration of Merchant Ivory’s work with the aptly titled “Merchant Ivory,” a documentary that explores the lives and work of Ivory and Merchant as well as other key collaborators — Jhabvala, composer Richard Robbins, actress Helena Bonham Carter — whose personal passions and relationships often intersected or collided in ways that wouldn’t be out of place in the emotionally complicated worlds Merchant Ivory often presented in their films. Soucy’s movie is a fascinating and entertaining exploration of a creative and romantic partnership and its tendrils over the course of 50 years, but it’s also a great crash course in Merchant Ivory cinema for those unfamiliar with it — and an inspiring summation of its excellence for longtime fans.

“I felt that the Merchant Ivory story needed to be told for cinema history,” Soucy told IndieWire. “Jim, Ismail, Ruth, and Dick Robbins had such a unique working relationship and the arc of the story was very compelling.” While John Pym and Humphrey Dixon had made a fine documentary about Merchant Ivory in the 1980s (“The Wandering Company”), it ended right at the moment when the team was about to have its greatest success to date with “A Room with a View” and enter its era of greatest success and productivity. For Soucy, it was important not only to include everything that happened in the Merchant Ivory partnership after that point, but also to explore the period after Merchant died unexpectedly in 2005.

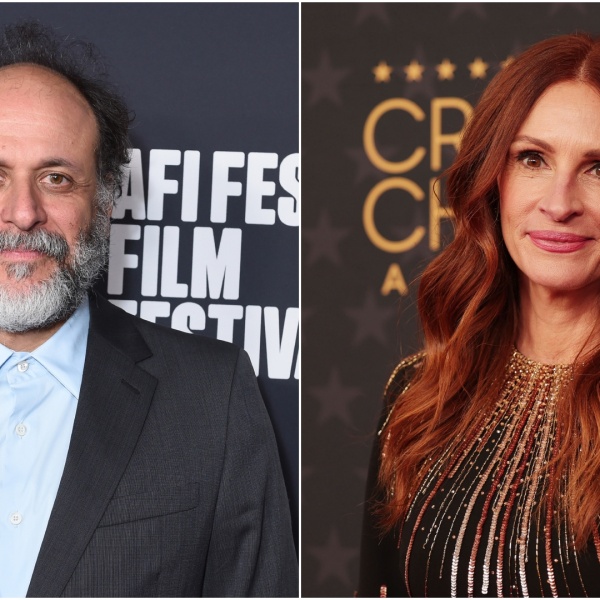

Ivory directed one film after Merchant’s death, “The City of Your Final Destination” in 2009, and its financial troubles basically ended the production company. Yet Soucy’s doc moves beyond that to show Ivory’s extraordinary third act, in which he won an Oscar for the screenplay of “Call Me by Your Name” at the age of 89. “That was kind of a random thing that happened,” Ivory told IndieWire. “The people who made ‘Call Me by Your Name’ were my neighbors and they just suddenly involved me in it.” Since that late-career triumph, the 96-year-old Ivory has experienced a surge of activity, adapting a Ruth Jhabvala short story (“The Judge’s Will”) for director Alexander Payne and writing an autobiographical short story that’s about to be published; he also curated “Ink and Ivory,” an exhibition of drawings from India and Pakistan currently running at The Met.

Though he’s busy moving forward, Ivory has found attending retrospectives of his work and revisiting it via Soucy’s documentary to be a pleasurable experience. “There’s not a single film of mine that I wish I hadn’t made, and that makes me happy,” Ivory said, noting that he’s particularly fond of some movies that weren’t well received on their initial release but seem to hold up when screened for audiences now. The back-to-back biographical films “Jefferson in Paris” (1995) and “Surviving Picasso” (1996), for example, play extremely well in the post-“Me too” era but were met with hostility when Ivory made them. “We had taken two cultural heroes and shown how they treated women, which wasn’t all that great. I think that harsh light was why they didn’t catch on — at that time people just didn’t want to hear it.”

One of the great pleasures of Soucy’s documentary is the light it shines on films like “Mr. & Mrs. Bridge” (1990), which Ivory calls his most autobiographical work, and “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries” (1998), which the director considers to be a personal favorite as he laments its lack of availability. “I love that film, but it doesn’t even have a distributor,” Ivory said. “It’s extremely hard to find.” For Soucy, “Mr. and Mrs. Bridge” is of particular interest thanks to its incredible performances by Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward (who was Oscar-nominated for the film) and vivid portrait of generational shifts in 1930s and 1940s Missouri. “It captures a time that’s gone,” Soucy said, “much like ‘Slaves of New York’ [1989], it’s a kind of time capsule.”

“Slaves of New York,” which Tama Janowitz adapted from her own popular novel, is another less successful Merchant Ivory project that finally gets its due in “Merchant Ivory.” “‘Slaves of New York’ was a box office disaster,” Ivory said. “I’m surprised Sony ever wanted to make films with us again.” Soucy interviewed Janowitz extensively for the documentary, and while her stories are terrific, there are many more where those came from. “I have all this extra footage, so I put the longer interviews on the website, merchantivoryfilm.com,” Soucy said. Anyone who wants more from Janowitz, Emma Thompson, Helena Bonham Carter, Hugh Grant or the other interviewees can simply click on the “bonus” page of the movie’s site.

When watching the interviews in the finished film, Ivory found himself surprised by his collaborators’ observations and memories. “I wouldn’t say I was horrified, but I was surprised,” Ivory said. “A lot of it was totally new to me, because when you’re directing there’s so much you have to deal with. Actors go so deeply into their roles and they’re pulling up stuff out of their natures and their own histories and you don’t know it at all. There’s still plenty that I don’t know — and I don’t know if I want to know!”