In 2008, Mike Leigh made a movie called “Happy-Go-Lucky,” in which Sally Hawkins played a school teacher named Poppy who was so irrepressibly buoyant and upbeat that her joy seemed like a taunting provocation to the misery of the world around her. Sixteen years later, the filmmaker returns to similar territory with “Hard Truths,” a searing but indivisibly empathetic drama about a British Jamaican woman so wretched that it might as well be called “Misery-Go-Fuck-Yourself.”

Pansy is to Poppy what Samuel L. Jackson’s Mr. Glass was to David Dunn — the existence of one implies the existence of the other. They will never cross paths, much as all of Leigh’s characters seem to occupy a shared universe that so honestly resembles our own, but if they did I suspect that it would result in an apocalyptic collision of psychic distress. And what a shame it would be to lose either one of these women. While Poppy is an SPF 100-strong blast of sunshine and Pansy might be the single most vituperatively unpleasant character the movies have ever produced, Leigh renders them both equally worthy of love — even if one of them seems to have nothing but hate on her mind.

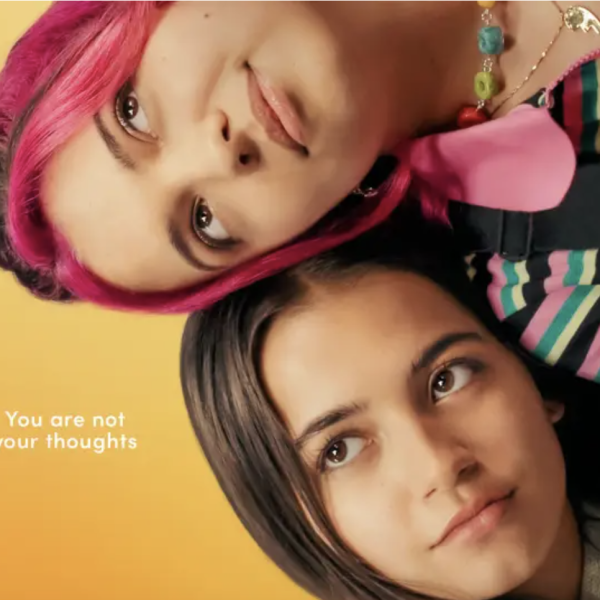

As played by an absolutely titanic Marianne Jean-Baptiste, whose performance somehow lives up to the standard that she and Leigh once set with “Secrets & Lies,” it would be impossible to overstate the raw spectacle of watching Pansy make her way through the world; a spectacle that Leigh exaggerates further by confining the character to a modest little film that’s only a touch bigger than the working class London home she shares with her husband Curtley (David Webber) and their stunted 22-year-old son Moses (Tuwaine Barrett). Of course, “shares” doesn’t accurately reflect the dynamic inside of a house that Pansy rules like a dragon, her hair-trigger fury so violent that Curtley and Moses tend to creep through the halls in silence (not that it helps), her grievances so pervasive they appear to have scared all traces of color off the walls. If anyone else dared to walk around in something as vibrant as Pansy’s soft pink bathrobe it would surely give her a migraine.

Pansy is unwell, though we sense that her relatives are reluctant to see her as such; Jean-Baptiste has stressed the importance of telling stories in which Black families aren’t framed in response to external forces, but the call is no less difficult to answer when it’s coming from inside the house. From an outside perspective, it would seem that Pansy is burdened by some combination of OCD, anxiety, and depression, all of which must have been exacerbated by the death of her mother and the social isolation of the pandemic that followed (COVID merits a passing mention). So far as Curtley and Moses are concerned, however, Pansy is just Pansy, and treating her like a problem to be solved would betray their unspoken pledge to suffer each other in the face of an insufferable world.

It’s hard to tell if they appreciate the rare moments when Pansy leaves the house. On the one hand, it’s a relief to think she might become someone else’s problem for a while. On the other hand, Curtley and Moses have to hear all about it when she comes home. “People!” Pansy spits through her teeth as she reports on a harrowing encounter with some (perfectly nice) charity workers. “I can’t stand them… Cheerful, grinning people.”

Pansy’s general distaste for humanity would make Mr. Burns seem big-hearted by comparison, but Leigh’s faith in the root humanity of Jean-Baptiste’s performance — and in the hurt that guides it through even the broadest moments of humor — allows him to indulge in a variety of laugh-out-loud setpieces without any risk of losing Pansy to caricature. We’re talking about a woman who can’t even shop for furniture or pay for groceries without bringing the wrath of God down upon anyone who dares to share her airspace. “Your balls are so backed up you’ve got sperm in your brain!” she yells at a guy who has the temerity to ask if she’s pulling out of a parking space. And lord help the poor dentist who’s tasked with poking around her mouth with a metal spike.

A harried encounter with a saleswoman implies that Pansy has a spot of self-awareness, but that only extends so far. “Why can’t you enjoy life?,” her sister Chantelle (Michele Austin) asks at one point. “I don’t know,” comes Pansy’s reply, her sudden anguish cutting through carapace-thick layers of bitterness and resentment with the clarifying speed of true vulnerability — a signature of Leigh’s cinema, and one that “Hard Truths” is able to crystallize with the strength of a diamond because of its modesty.

Chantelle emerges as the backstop this movie needs to keep Pansy from bludgeoning it into the ground, as the bubbly and sociable hairdresser is both the antithesis of her sister in every way, as well as the person closest to her pain. The obvious fact of Chantelle’s joy — and the success of her two adult daughters, who feed off her strength in order to survive the indignities of their high-pressured jobs — serves to stress the devastating ripple effects of Pansy’s negativity, which in turn allows it to highlight the persistence of the love that people still have for her despite everything. Pansy is not an easy woman to accommodate (the explosive volatility of Jean-Baptiste’s performance becomes so palpable that a simple wide shot of her stewing in the middle of a family reunion creates all the bomb-under-the-table suspense of a Hitchcock setpiece), but her difficulty only makes the effort all the more urgent.

Leigh explores these feelings with the softly familiar touch of a late work, but even in this small portrait of a story he remains peerlessly sensitive to how life grows around the hurt that threatens to stop it in place; he waters the weeds that more didactic filmmakers would instinctively try to pull out of the ground, and in doing so digs up a degree of compassion that belies the scabrousness of the world itself. There’s no instant cure for Pansy’s condition; no emotional breakthrough that will put a stop to her downward spiral or heal the pain that she’s forced her son and husband to suffer in silence.

Per its title, “Hard Truths” doesn’t go in for easy fixes, and the film seems to end in much the same place as it starts. But it doesn’t. Not quite. The earth might quake wherever Pansy goes, but the film’s real power is in watching her family hold on to the shared history that she threatens to uproot. “I love you,” Chantelle tells her. “I don’t understand you, but I love you.” It’s a message that Leigh has been trying to convey to his characters for more than 40 years, and one that has seldom been so natural to accept for ourselves.

Grade: B+

“Hard Truths” premiered at the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival. Bleecker Street will release it in theaters on Friday, December 6.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best reviews, streaming picks, and offers some new musings, all only available to subscribers.