John McNaughton is a filmmaker without prejudice when it comes to genre or budget; the stark horror of “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer” is as far from the deliriously gorgeous excess of “Wild Things” as that film is from the experimental documentary “Condo Painting,” and “Mad Dog and Glory” proves McNaughton could have been an accomplished studio stylist had he chosen to go that way.

The variety in his work stems from how McNaughton has always seen directing — and life — as an endeavor that necessitated trying new things. “Before I became a filmmaker, there were many things I wanted to do, and I did them,” McNaughton told IndieWire. “I joined a traveling carnival, built sailboats, and when I lived in New Orleans, I wound up buying silver jewelry and cutting gemstones. Because life is an adventure. And once I became a filmmaker, it was a similar thing.”

From September 19 to October 7, the Nitehawk Cinema will showcase McNaughton’s work in all its breadth with “Portraits of Wild Things: The Films of John McNaughton,” a series that includes the aforementioned movies as well as rarities like “The Harvest,” “The Borrower,” and “Normal Life,” with McNaughton appearing in person for Q&As following several of the films. It’s one of the major retrospective events of the season, a chance to take a deep dive into the work of a great but still somewhat underrated director.

While McNaughton’s genre-hopping and tendency to move back and forth between ultra-low-budget indies and well-resourced studio (and network TV) fare have made it difficult to see the common threads in his work, critic Roger Ebert did notice one strong through line: “McNaughton seems fascinated by the ways in which lawlessness is infectious.” That’s a theme that runs through most of the work on display at the Nitehawk, but it’s particularly prevalent in “Normal Life,” McNaughton’s 1996 crime film starring Luke Perry and Ashley Judd as lovers whose lives end in tragedy after they embark on a bank-robbing spree.

Revealing the story’s grim outcome isn’t giving anything away, because McNaughton begins his story at the end and then tells the lovers’ saga in flashback, a device that gives the whole movie a fatalistic tone — even when Perry and Judd have brief moments of genuine happiness, the romance is tainted by the fact that we know it can’t last. “I was reading Greek tragedy at the time,” McNaughton said, “and that’s how Greek tragedy is laid out. You start out with the result, and then you go back and tell the story of how you got there.”

The framing device infuses even the most prosaic moments with poignancy, and the film’s emotional impact is made greater by the knowledge that it was based on a true story. “One of the things that was so touching and sad was that when they got a little money, he opened a used bookstore,” McNaughton said. “And it was actually a good used bookstore. It wasn’t a front to hide money. They bought a little house in the suburbs and opened a used bookstore, and then died in gun battles. The story was really tragic because they weren’t going to be wild outlaws like Bonnie and Clyde. They wanted a normal life and just couldn’t achieve it in that economy.”

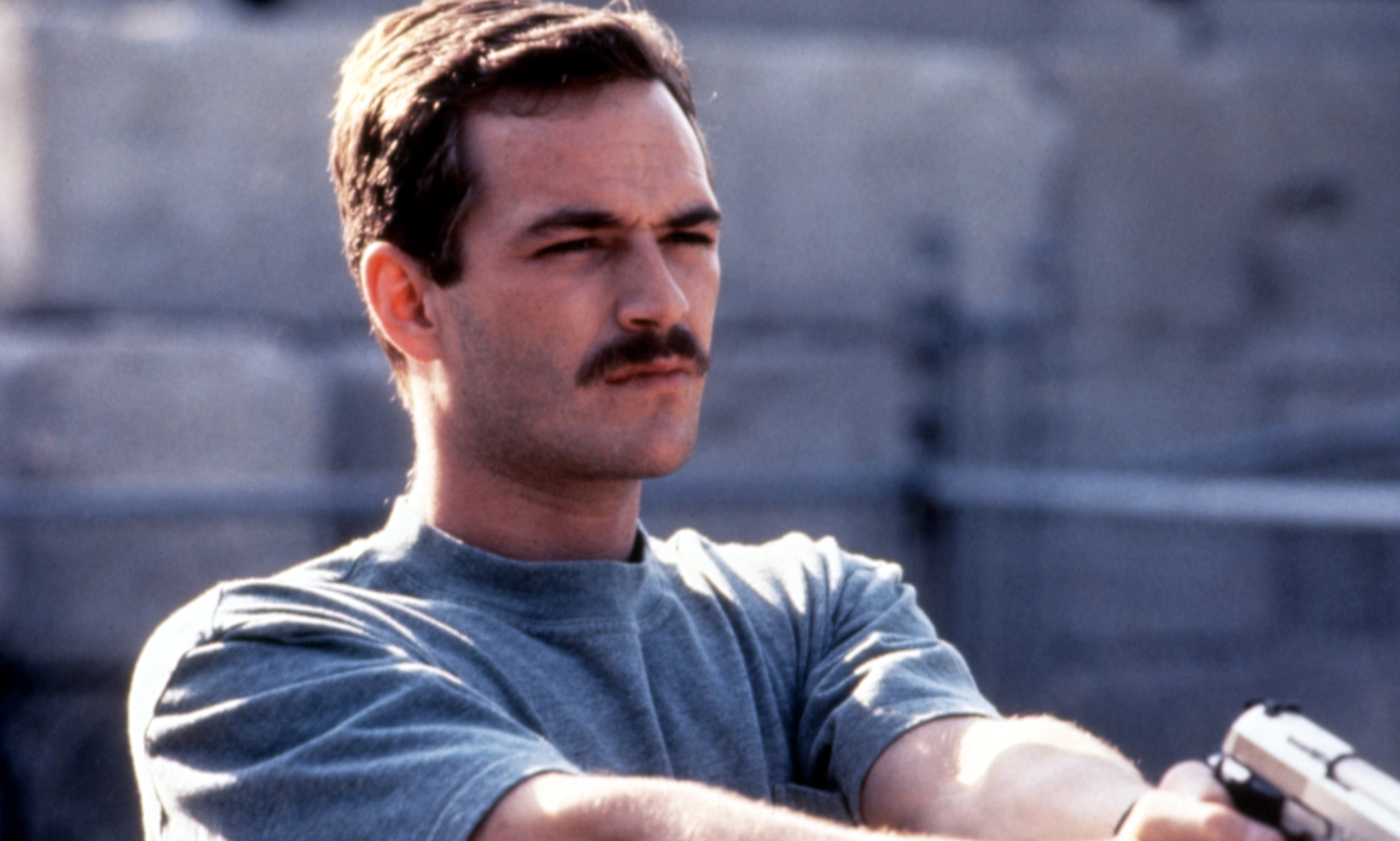

A large part of the film’s power comes from the casting of Perry and Judd, who give heartbreaking performances as the doomed couple. Perry, in particular, is a revelation for anyone whose familiarity with his work is limited to his stint as heartthrob Dylan McKay on “Beverly Hills 90210,” a show McNaughton had never even seen when he cast the film. “I was too old for that show by then,” he said. Although McNaughton knew Perry was a teen idol, he kept his mind open about the possibility that the actor could handle the complexity of the role in “Normal Life.” “I learned a long time ago, always meet the actor, because you never know.”

McNaughton met with Perry and immediately liked him, and when he met and was impressed by Ashley Judd (then coming off of Victor Nunez‘s “Ruby in Paradise”), he knew he had his cast. Because “90210” producer Aaron Spelling was trying to promote Perry as a movie star, and McNaughton’s agency William Morris wanted to make Aaron Spelling happy, it was clear that with Perry in the lead, the movie would get made — though Perry’s casting created challenges when it came time to release the film.

“There was a management change at Fine Line, and the people who actually agreed to produce the movie left,” McNaughton said. “A new team came in, and the head of production was against the movie before she even saw it. She didn’t think Luke Perry was a movie star and didn’t want to be in business with him. It never had a chance in that respect.” When a test screening did poorly — likely because “90210” fans drawn to the theater by Perry weren’t prepared for the film’s bleak tone — the executive had the excuse she needed to dump the movie.

“Normal Life” was barely released, but it remains one of McNaughton’s best and certainly most underseen films, making the opportunity to see it on 35mm at the Nitehawk all the more valuable. When the movie came out in 1996, it got lost among a series of crime movies revolving around a romantic couple; aside from the Quentin Tarantino-penned “True Romance” and “Natural Born Killers,” the early-to-mid-’90s saw the releases of “Love and a .45,” “Kalifornia,” “The Chase,” and the Alec Baldwin-Kim Basinger remake of “The Getaway,” among others.

But “Normal Life” cuts deeper and hits harder than any of these films, because there’s no buffer of genre or ironic humor between the action and the audience. Like “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer,” the movie connects the viewer to the characters’ nervous systems with no dilution and no distance, and makes great use of authentic locations — McNaughton even shot at one of the banks the real-life couple robbed. “We used so many locations where the story had actually happened,” McNaughton said. “For the bank in the movie that was a bank they really robbed, we were using actual employees in the scene, and the manager of the bank was the manager who was there the day of the robbery. It provided an odd vibe.”

Talking to the bank manager gave McNaughton the kinds of specific, realistic details he revels in; there’s no such thing as a conventional action scene in “Normal Life,” because even in the chases and shoot-outs, the director is so focused on how the drama would actually unfold in the real world that he makes it look like something you’ve never seen before. McNaughton wants to know what it really feels like to steal a car, or listen to the authorities closing in on your fugitive wife over a police radio, or aim a gun at someone or have it aimed at you — and he knows how to make you feel it through his unobtrusive but flawless sense of camera placement, editing and sound design.

On “Normal Life,” that style grew largely out of McNaughton’s collaboration with cinematographer Jean de Segonzac, with whom he had worked on the TV show “Homicide.” “He was perhaps the best handheld cinematographer that ever walked the earth,” McNaughton said. “We had a rhythm and a communication and could move really fast, and he was so fluid with the camera that you couldn’t tell it was handheld.”

While de Segonzac’s run-and-gun style was right both artistically and practically for the modestly budgeted “Normal Life,” McNaughton also enjoyed working with the temperamentally opposite Jeffrey Kimball on “Wild Things.” “With him, you don’t get a lot of setups every day, but they’re gorgeous because of his lighting style, which is not fast or guerrilla — it’s studio.” That McNaughton’s resume could span both kinds of filmmaking is a testament to both his talent and his range of interests, though he acknowledges that a lot of one’s career depends on chance.

“There’s a certain amount of coincidence that has to do with what’s available in the moment and what comes your way,” McNaughton said. His debut film, “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer,” only came about because another intended project — a documentary about professional wrestling — fell through. “I made a horror film because that’s what was available to me, and when you get to make your first film, you don’t ask too many questions.”

McNaughton feared that he would get pigeonholed as a horror director, but “Henry” found a powerful fan in Martin Scorsese, who hired McNaughton to direct “Mad Dog and Glory” as his first studio film. “To get that call was quite a thrill,” McNaughton said. “I worshipped his movies. I remember when I went to see ‘Mean Streets’ with a bunch of my knucklehead friends from the south side of Chicago, and we looked like the people in that movie. It was like we were watching a movie about our lives and our friends.”

Although McNaughton credits Scorsese with saving him from getting stuck in horror, he did return to the genre to great effect with “The Borrower” and “The Harvest” and acknowledges its importance in his career. “I love horror films, but I love other kinds of films even more,” McNaughton said. “I spent a lot more time watching Ingmar Bergman films than William Castle films as a youngster.” In any case, he’s excited to revisit his work and share it with audiences at the Nitewhawk. “I don’t watch my movies at home, but it’s fun to see them projected. I haven’t been to New York since before the pandemic, so I’m looking forward to it.”

“Portraits of Wild Things: The Films of John McNaughton” begins on September 19 at the Nitehawk Cinema.