While the “Nine Old Men” are well-documented and justly praised as the legendary animators of the Disney classics overseen by Walt — “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (1937) through “The Jungle Book” (1967) — it’s gone unnoticed how the directors made their mark on these movies. That changes with the release of “Directing at Disney: The Original Directors of Walt’s Animated Films” by Disney historian Don Peri and Pete Docter, Pixar’s chief creative officer and Oscar-winning director of “Soul,” “Inside Out,” and “Up.”

Peri and Docter, who spent more than a decade on the book, reveal for the first time the organizational structure for directing at Disney and how the role of the director progressed. Peri, who had a fundamental understanding of how films were made at Disney, spent years at the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, combining interviews, documentation, and a diary into a methodology of the directors’ roles and how they collaborated with the animators.

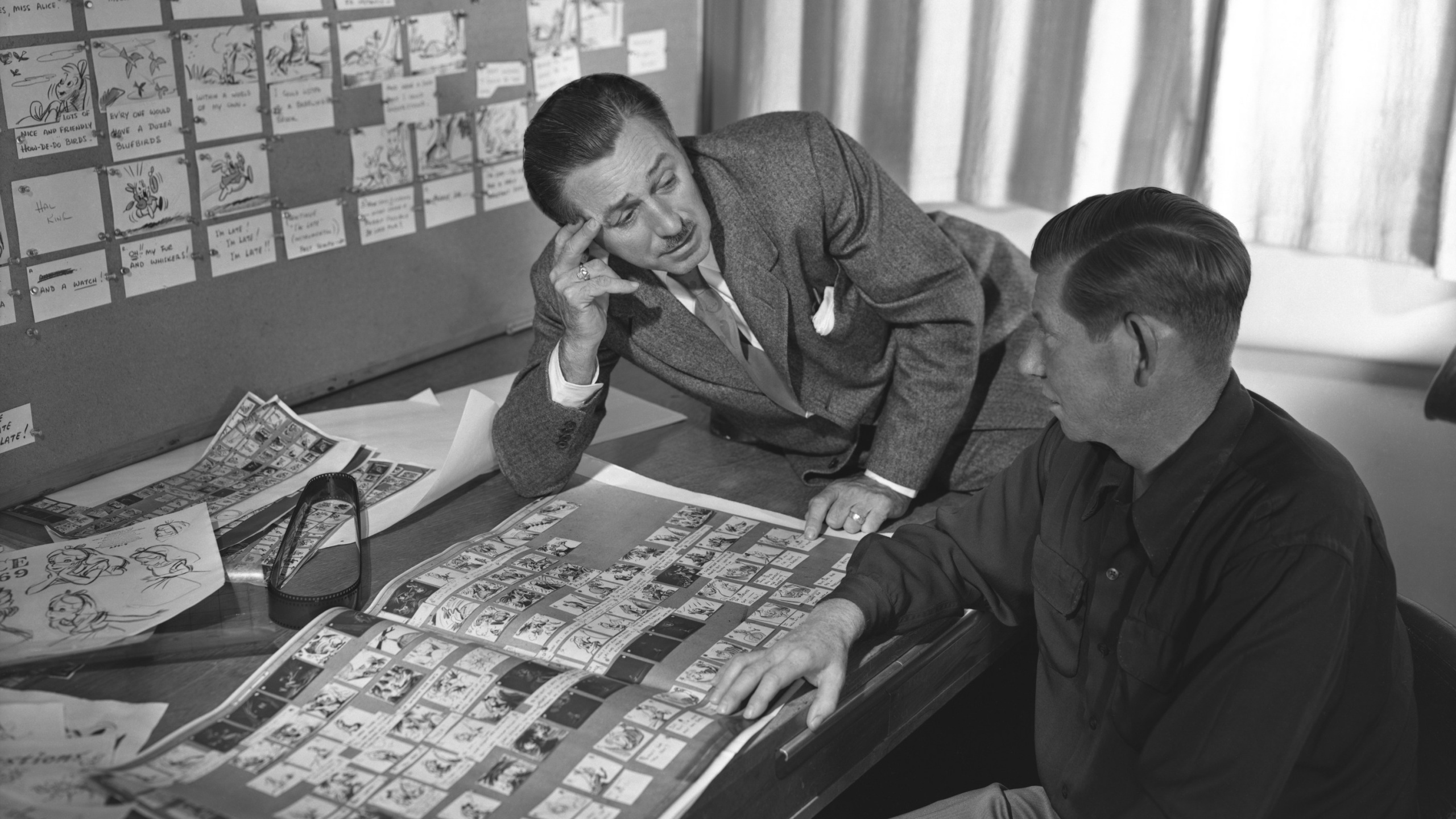

On the early features, the directors were known as supervising directors, overseeing the work of sequence directors, who previsualized and planned their sections with the animators and worked with the voice actors until the mid-’60s. But Disney oversaw every facet of production, focusing on story, and had final approval of everything. Then a supervising producer role was introduced in the ’40s and the directors took on greater responsibility in implementing Disney’s creative vision through the ’50s and ’60s, when he was more actively involved in producing live-action features and overseeing the theme park and TV shows.

For Docter, who’s always been curious about how directors worked at Disney under Walt, this was an opportunity to learn more about who the directors were and what they did. “I think, for me, I was most comforted by the fact that they changed,” Docter told IndieWire. “I think as a kid, I always had this idea that Walt Disney was just a genius and that everything sprung fully formed from his brain. And then you go read the thing and they’re throwing stuff out left and right. The same as we’re doing today.

“I remember talking to [animator] Joe Grant [‘Dumbo’] about that,” continued Docter. “I got to know him in the late ’90s and early 2000s. And I would say, ‘What was it like back then?’ He would say, ‘It’s the same.’ So it was really, for me, how much of the stories were fleshed out? I know, obviously, the first couple of ones that Walt was intimately involved with [‘Snow White’ and ‘Pinocchio’], he seemed to have it fleshed out.

“But one thing that shocked me was they didn’t do story reels [in the beginning] like we do today. You write it and then you put it up and you watch the whole thing and that’s how you know whether it’s all working. And Walt would just carry that around [in his head]. They would pitch it, and he would know whether it clicks into the movie and is right or not, which is amazing. So the director was much more like, here’s what Walt wants when giving it to the animators.”

And yet on “Peter Pan,” they still hadn’t worked out Captain Hook’s personality during production: Was he foppish, erudite, or just menacing? “And Walt says something like, ‘Well, see what [animator] Frank [Thomas] does with it,’” added Docter. “And so that sort of shift, to even like knowing the bones of what the character is all about, that feels like something that wouldn’t have happened in the earlier days. But it’s also a shift to a real focus on performance and depends on the animators. That was not there in the early days.”

The main focus of the book is on the primary directors: David Hand, who was a great organizational leader, was the sole supervising director on “Snow White” and “Bambi”; Ben Sharpsteen, who worked on “Pinocchio” and was the sole supervising director on “Dumbo,” helped provide an economy and clarity on the latter film that recalled the best of the Disney shorts. But Wilfred Jackson (“Cinderella,” “Alice in Wonderland,” “Peter Pan,” and “Lady and the Tramp”) was the most talented director, who knew how to bring out the best in the animators and had a flair for musical scenes.

However, Clyde Geronimi (“Cinderella,” “Alice in Wonderland,” “Peter Pan,” “Lady and the Tramp,” “Sleeping Beauty,” “One Hundred and One Dalmatians”) was the most controversial director for his inability to communicate what he wanted and was thought of as a tyrant by several animators. Wolfgang Reitherman, the last director to collaborate with Disney, worked solo on the disappointing “The Sword and the Stone” and the smash hit “The Jungle Book,” specializing in action and character personality.

“I think these directors came in at a certain point to tell the animators what Walt wanted, and one of the concerns was they wanted to hear it directly from Walt, and they didn’t usually get to do that,” Peri told IndieWire. “Sometimes they would hold their scenes and not put it into the reel until right before the meeting. So Walt would see it before the director could block it. And then they could get around the director. Frank Thomas did that with the rolling meatball in ‘Lady and the Tramp’ before Geronimi could see it and [possibly] cut it.

“One of the great joys of writing the book,” Peri continued, “was changing the narrative from the animators to the directors. The movie is made on a larger scale. And so not only did we get to bring to light some of these people that nobody knew about, but really to look at the process of how these movies got made.”

For Docter, what he learned from the book will apply to his own career at Pixar in nurturing the next generation of directors and storytelling. “There’s so much out there and it’s very difficult to feel like I’m doing something that’s new that people haven’t seen,” he said. “Although I guess, for me, that goes back to the [Reitherman] and Walt thing that if you can create a believable character that you care about in a relationship, if it’s done well, there is endless variations on that.”