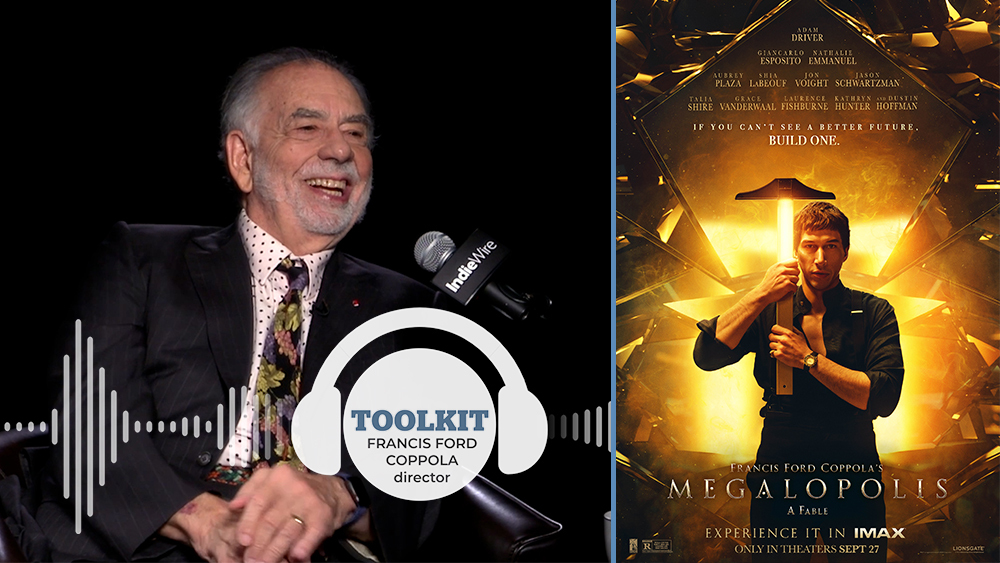

I was the first interview of the day: 30 minutes on camera for the Filmmaker Toolkit podcast (you can watch the full conversation above), and I was trying to end the interview. Time was up. The army of publicists and crew had a full day planned, and Francis Ford Coppola was still talking. I’m not going to flatter myself that Coppola was so engaged talking to me that he didn’t want the conversation to end, but he seemed bothered by the vibe. The sense we were on the clock. That talking about art was a job for everyone else in the room, including me. Standing, as I waited for the lav mic to be detached, Coppola asked, “What was the question you wanted to ask me but didn’t?” Knowing the professionals running the press day wanted me out ASAP, I flipped the question on him and asked what it was he had wanted to talk about that hadn’t been asked.

Coppola lit up as he started talking about the future of cinema, how video games and his dreams of live cinema could merge into something new. The sound was no longer recording, so I’m not going to attempt to paraphrase — like “Megalopolis,” the man can weave together seemingly disparate threads in a way that makes complete sense — but here was a man at 85 years old, who had made some of the greatest films ever, and what got him excited was the conviction cinema had only just scraped its true potential.

That spirit is at the heart of “Megalopolis,” a film that connects the fall of Rome to what it sees as the inevitable fall of the U.S., but that simultaneously still believes in the dreamers and the power of human ingenuity to build a better future. The film’s ending is a plea for a great conversation about what we want our world to be in the future, as Coppola hopes “Megalopolis” becomes a New Year’s Eve movie, one we all watch when setting our resolutions.

When his trusted publicist came over with a cup of coffee, he asked, gesturing to the two dozen people standing on the periphery, “Are all these people here to play?” At first I assumed this was a director wanting to make sure anyone without an immediate task be cleared from set, but his intention was the opposite: He went into a monologue about how virtually every great human achievement came from play, not work. It was a message directed at me as much as everyone else. I’d just gotten 30-minutes with someone who had shaped my understanding of cinema: Had I just blown that opportunity with a work-like approach, with dutiful, well-researched questions about the making of the film, when his mind was on grander ideas? When IndieWire’s executive video producer asked politely for a photo to promote the podcast, he turned toward her and in a grandfatherly tone scolded, “You aren’t here to play.”

Coppola spent $120 million of his own money to make “Megalopolis” in order to play. While on the podcast he talked about how an idea he first conceived of in the 1980s constantly evolved, in part by creating a space and process built around theater games.

“Actors never knew what I was going to ask them to do, which is part of the fun of it,” said Coppola. “The fun of working with actors is that in the space where you are, which is say here, you can’t get in trouble, right? You can’t be bad, right? In other words, we’re gonna play together and we’re gonna have fun together.”

While Coppola is a visionary director, he insists he’s unable to visualize and imagine his film beforehand. Using examples from previous works, “Apocalypse Now” and “Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” he talked about how films reveal themselves as they are being made, and his job was to listen and follow. By the time he went to shoot the ending of “Apocalypse Now,” the film had drifted so toward the surreal that the scripted military battle finale no longer made sense. It’s with pride Coppola recalled Marlon Brando calling him on it.

“[Brando] came aboard, and the first thing he said to me, ‘Oh, you painted yourself into a corner, haven’t you?’” said Coppola. “So that’s exactly what happened in another category with ‘Megalopolis’ is that I was doing unusual things with the actors.”

“Megalopolis,” in many ways, took this principle to the max. If there was one underlying motivation driving the film over the decades, it was a project for Coppola to discover his own style after a career working in various genres and off scripts by other great writers. After going off the Hollywood grid to rediscover his craft, working on low-budget films, Coppola was ready with “Megalopolis” to learn who he really was as an artist.

“I was making a movie that [was] something I’d never seen before, and I didn’t know how to make it,” said Coppola. “And little by little, the movie started to become something in this weird group improvisation.”

He created and paid for an enormous canvas to play on with a team of collaborators. Why? Because it’s the only way he believed to tap into the immense human capabilities inside each of us. And even at something as cooly orchestrated as a routine hotel presser, he was going to make sure everyone in his orbit knew there was only one way to properly work.

To watch the full Toolkit conversation with Francis Ford Coppola, see the video at the top of the page. You can also subscribe to the Toolkit podcast on Apple, Spotify, or your favorite podcast platform.

“Megalopolis” opens in theaters nationwide on September 27.