When cinematographer Lawrence Sher and director Todd Phillips made the first “Joker” in 2019, they quickly learned that they couldn’t predict what star Joaquin Phoenix was going to do in any given take — and that spontaneity was one of his, and ultimately the movie’s, greatest strengths. In order to give the actor maximum flexibility (and themselves the ability to catch his best moments on the fly), Sher and Phillips developed a method of shooting with no rehearsal, no marks, and unobtrusive lighting from sources that are always based in reality.

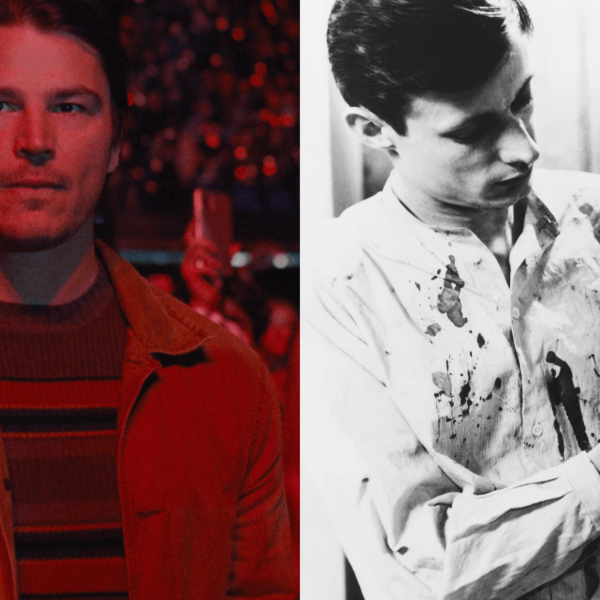

That style worked well enough on “Joker” to nab Sher and Phillips Academy Award nominations — and Phoenix an Oscar — but it was a gritty drama with roots in 1970s Lumet and Scorsese. The sequel, “‘Joker: Folie à Deux,” is a musical, a genre typically associated with lush fantasy, elaborate choreography, and precisely conceived visual design. Could an approach that had more in common with the work of John Cassavetes than Vincente Minnelli still work in the new context?

“In fact, we did it on steroids,” Sher told IndieWire. “That style had worked really well, and Joaquin really responded to it, so we pushed it further. I think most people — even myself — would think, well, it’s a musical. The conventional thing that works is you break the song in parts, you shoot this section here and the next verse there, and you choreograph it and rehearse. That was never going to be our style because the music is still a reflection of the overall language of the movie. It’s just a replacement for the dialogue.”

Although “‘Joker: Folie à Deux” has meticulous compositions and gorgeous lighting, Sher said the frames were always determined “between take one and take five.” “They’re all found in real-time,” Sher said. “There’s never any rehearsal or any marks.” Working closely with production designer Mark Friedberg, Sher and his team would light the 360-degree sets from windows and practicals that would give Phoenix and costar Lady Gaga the freedom to move wherever they wanted; during the takes, Sher would communicate with his crew via headsets and shoot the action as if covering a live sporting event.

Even for the most classically artificial musical number, in which the stars dance on a rooftop, Sher maintained maximum flexibility. He established lighting sources like the moon and a “Hotel Arkham” sign and then came up with an overall visual design that would work no matter what the actors did, utilizing the blue tones associated with the Joker but bringing in warmer colors to express the significance of Gaga’s Harley Quinn in his life.

“The biggest decisions we had to make in advance are things like color,” Sher said. “What we’ll do is present a lot of color ideas that we can quickly show Todd before the actors show up on set, just to give a mild pitch of the color and lighting. But the first time we see the idea and all those lighting changes in action is during the first take.” Rather than breaking scenes up into pieces for coverage, Phillips’ method was to shoot each scene from beginning to end, even when the focus was on getting close-ups or other small pieces, an approach that Sher said allowed for plenty of discoveries and happy accidents on set.

The first musical number in the film, when Phoenix’s Arthur Fleck sings “For Once in My Life” after meeting Harley Quinn, is a case in point. It’s an exquisite marriage of camera movement and blocking, as Arthur’s exuberance finds its visual corollary in the dreamy, lyrical frames in which the camera itself seems to dance with the actor. Although Sher shot some additional material that was ultimately cut in, it’s essentially one shot conceived in reaction to Phoenix’s movements.

“That might have been the third time we did that scene,” Sher said. “Every setup goes all the way through, but the first one might just be so Todd and Joaquin can understand what the scene is; it’s a little wider to allow us to see where things might go. That’s when we figure out that the scene can probably work as one shot, then in the second setup we basically clear everything out, and I’m watching through the lens as if I’m already watching the movie. My team asks, ‘What are we going to do?’ and I say, ‘Just listen to my voice, we’re going to figure it out.’”

That’s when those whisper-quiet headsets come into play, as Sher communicates with his dolly grip, crane operator, focus puller, and others in real-time. “I’m just like, ‘Let’s widen out here. I’m going to pan. OK, as he comes around, I want to wrap the camera behind him. As he comes here and pauses, I want to get in front of him and let that take us to the end.’”

Although the technology has improved and the scale has increased, for Sher, “Joker: Folie à Deux” is simply the next step in the evolution of a style he and Phillips began formulating 15 years ago on “The Hangover.” “It’s a philosophy that has kept building with every movie,” Sher said. “I don’t ever want the actors to think about the camera in a way that makes them leave the moment that they’re in — we have to do anything we can do to allow that and be flexible to their needs.”

The most impressive thing about “Joker: Folie à Deux” is that Sher does this without compromising the elegance of his compositions or the beauty of the lighting; the movie combines the raw immediacy of cinéma vérité with the formalism of one of those classic Minnelli or Stanley Donen musicals. “I can still find precision in the frames even with the seeming constraints,” Sher said. “They’re not mutually exclusive. It’s not like I need the actors to stand in one place to find something that feels like a dynamic or beautiful frame. I can find it. In fact, it’s almost more exciting because we’re all finding it together.”