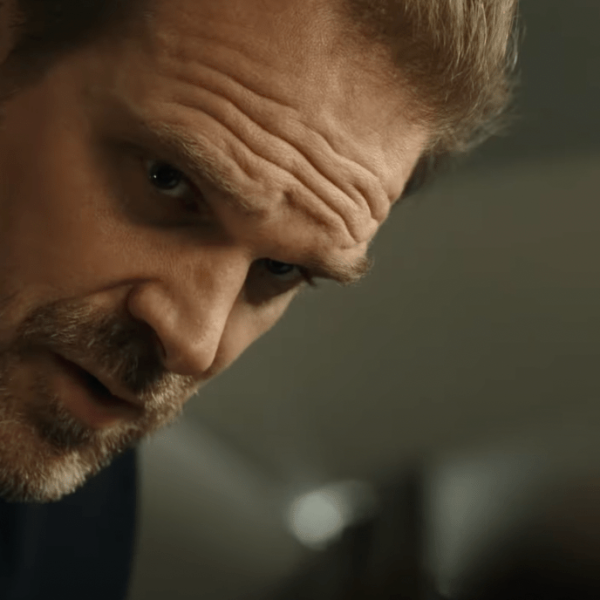

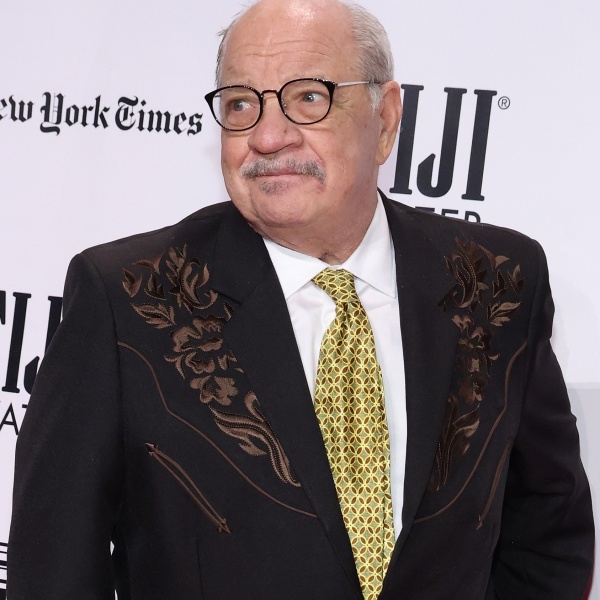

When director Ali Abbasi approached cinematographer Kasper Tuxen (“The Worst Person in the World”) about shooting “The Apprentice,” a fictionalized study of the relationship between Donald Trump (Sebastian Stan) and his mentor Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong), his pitch was simple. “He asked me if I was up for something super punk rock,” Tuxen told IndieWire. “He wanted to do something very raw, not something to show off for our colleagues. Sometimes you find yourself asking, ‘What are other DPs going to think of this?’ For this film, I let that all go.”

Adopting a more stripped-down, gritty style was in keeping with Tuxen and Abbasi’s background. “We were both trained at the Danish national film school,” Tuxen said, noting that he was influenced by the new wave of Dogme movies that were prominent just before he began his studies. “We come from small crews with very little equipment, where you don’t overcomplicate things or lock yourself in with too many trucks and too much gear.”

That minimalist approach allowed Tuxen to shoot “The Apprentice,” an ambitious period piece spanning several years, in just 25 days. “And some of those were pre-shoot days with a skeleton crew,” he said. The film is an astonishing example of maximizing limited resources, with a sweep and scale that belie the movie’s run-and-gun independent methodology. Tuxen revealed that a lot of the size came from a generous use of period stock footage, which in turn motivated the entire visual style of the movie.

“We understood quite quickly that we couldn’t create all these wide shots of 1970s and 1980s New York, and that we would have to use stock footage,” Tuxen said. “So we decided, why not just imitate the press cameras of the time?” “The Apprentice” flawlessly recreates the grain and texture of the 1970s 16mm news cameras, and as the movie moves into the next decade, the look shifts to broadcast video, reflecting the changing aesthetic of TV news coverage.

This approach serves both Tuxen’s practical need to match his stock footage (and enables him to seamlessly recreate the look of real TV interviews with Trump from the time) and the movie’s thematic arc toward moral disintegration; as Trump’s values collapse, so does the imagery, resembling less anything one is used to seeing in a typical bio-pic than a VHS copy of a Jane Fonda workout video from the 1980s.

Although Tuxen tested 16mm and various vintage video formats, he ultimately opted to shoot “The Apprentice” on an Alexa 35, using only a small part of the sensor to utilize a 16mm Zoom lens. Colorist Tyler Roth created a series of LUTs based on Tuxen’s initial tests that enabled him to meticulously replicate the looks he wanted as the movie passed through the early years of Trump’s rise to fame and fortune.

Throughout the movie, the guiding principle was not to make things pretty. “We only lit when we didn’t have exposure,” Tuxen said. “We were fine with double shadows.” The only time Tuxen brought in HMI lights was to simulate summer since the film shot in Toronto in the winter. Once the two basic looks — 16mm and broadcast video — were decided, Tuxen felt liberated by the freedom to aim his camera wherever he felt the most interesting things were happening, without allegiance to the niceties of composition. “I’ve never felt as free as I did on this film,” he said.

That sense of freedom was enhanced by the decision to shoot mostly with one camera, so that Tuxen could aim the lens anywhere he wanted without worrying about matching eyelines or picking up another camera in the frame. According to Tuxen, the sense of liberation was felt by the actors as well, and is part of what allowed Stan and Strong to make bold choices. “They weren’t waiting for us to turn the lights around,” he said, though the massive amount of footage they shot created stress for the editors later on. “They could barely watch all the footage in time to have the movie ready to submit to Cannes.”

The early passages of “The Apprentice” resemble some of the great films of 1960s and 1970s New Hollywood, and once again, some of Tuxen’s reference points were helpful not just from a creative standpoint but a practical one. When he needed to turn a contemporary Toronto street into 1970s Wall Street, he simply put a long lens on the camera “like ‘Midnight Cowboy.’ We couldn’t afford to fill the city with old cars.” With careful blocking and lensing with shallow depth of field, Tuxen was able to turn financial limitations into creative decisions — and make one of the most exciting movies of 2024 in the process.