A man-like creature — one that resembles a sentient peanut with a pair of stick legs and a severe overbite — is watching his partner wash their newborn baby when he’s suddenly distracted by the little basin being used as a bath. That little semi-circle activates something within him. A repressed and wounding memory from his childhood erupts into an idea that will rewire his species’ relationship to time itself, and our humanoid peanut friend begins to obsessively toil away at his new invention at the expense of being present with his family.

What that invention actually does is somewhat difficult to say; my best guess is that it allows people to Zoom with a younger version of themselves. But the sad fact of its origin story — which spans the first chapter of Don Hertzfeldt’s seemingly infinite 21-minute new short — is as obvious as the one stray hair on the Mr. Peanut’s head: Confronted with the most literal manifestation of his own mortality (his infant son), our hero retreats into the deepest reaches of his own mind rather than embraces the idea that he’s no longer only living for himself.

The award-winning device he retrieves from the darkest hollows of his shell has a recognizably seismic impact in that it invites people to see both everything and nothing that exists beyond themselves; to explode the finite boundaries of their physical existence at the same time as it shrinks their entire universe down to the size of the metal domes they wear on their heads. The echo chamber of its users’ own experience becomes a cocoon that protects them from the same cruel and unyielding world that Mr. Peanut’s technology hastens toward oblivion. With “ME,” which recalibrates the mordant despair of his previous work into a wordless musical that feels appropriately new and familiar at the same time, Hertzfeldt suggests that narcissism has become our shared defense against a pain that none of us can ever hope to escape by ourselves. That’s how I see it, at least.

Originally conceived in collaboration with an unnamed rock band (obviously but not officially Arcade Fire), and meant to be soundtracked by the songs from said band’s 2022 album (which may or may not have been called “WE,” and may or may not have been insufferable), “ME” was thrown into complete disarray when something happened to it toward the end of its production. Was it this? Who could say.

In the gracious but transparent note that Hertzfeldt included along with the film’s release on Vimeo last weekend, he referred to the incident only as “extenuating circumstances,” writing that “I found myself in the strange position of having nearly completed a musical that suddenly no longer had any music in it.” It would take an entire year for the “It’s Such a Beautiful Day” director — who largely makes his films by himself — to salvage his effort and reimagine what the project could be. Insisting that “the picture that’s somehow still standing is leaner, more raw, and arguably stronger than it would have been had everything gone right,” Hertzfeldt says that the “ME” he rescued from all that mess isn’t “a dog that’s missing a leg” so much as it’s “a dog that now has wings.” And sure, Hertzfeldt notes, maybe dogs aren’t supposed to have wings, but this one does, and they carry the movie attached to them well into the stratosphere by the time it’s over.

We’ll never get to see the incarnation of this short set to the veritable self-parodies of a once-great band, but I have no trouble taking Hertzfeldt’s word that this version is better. On the other hand, I have all the trouble in the world imagining how “ME” — or any of Hertzfeldt’s movies, for that matter — would retain its casually devastating comic darkness when paired with the oppressive sincerity of Win Butler’s songwriting (to name just one of the countless frontmen who may have been involved with this project).

Sincerity is crucial to Hertzfeldt’s work, but only because of the duet it creates with his gutting deadpan. Hertzfeldt’s films are rooted in the dissonance between the epic scope of human feeling and the sketch-like smallness of human existence (there’s a reason why they continue to offset their stick figure characters with the divine splendor of classical music). That dissonance is made all the more profound by the expressively crude — if deceptively sophisticated — animation that brings those characters to life.

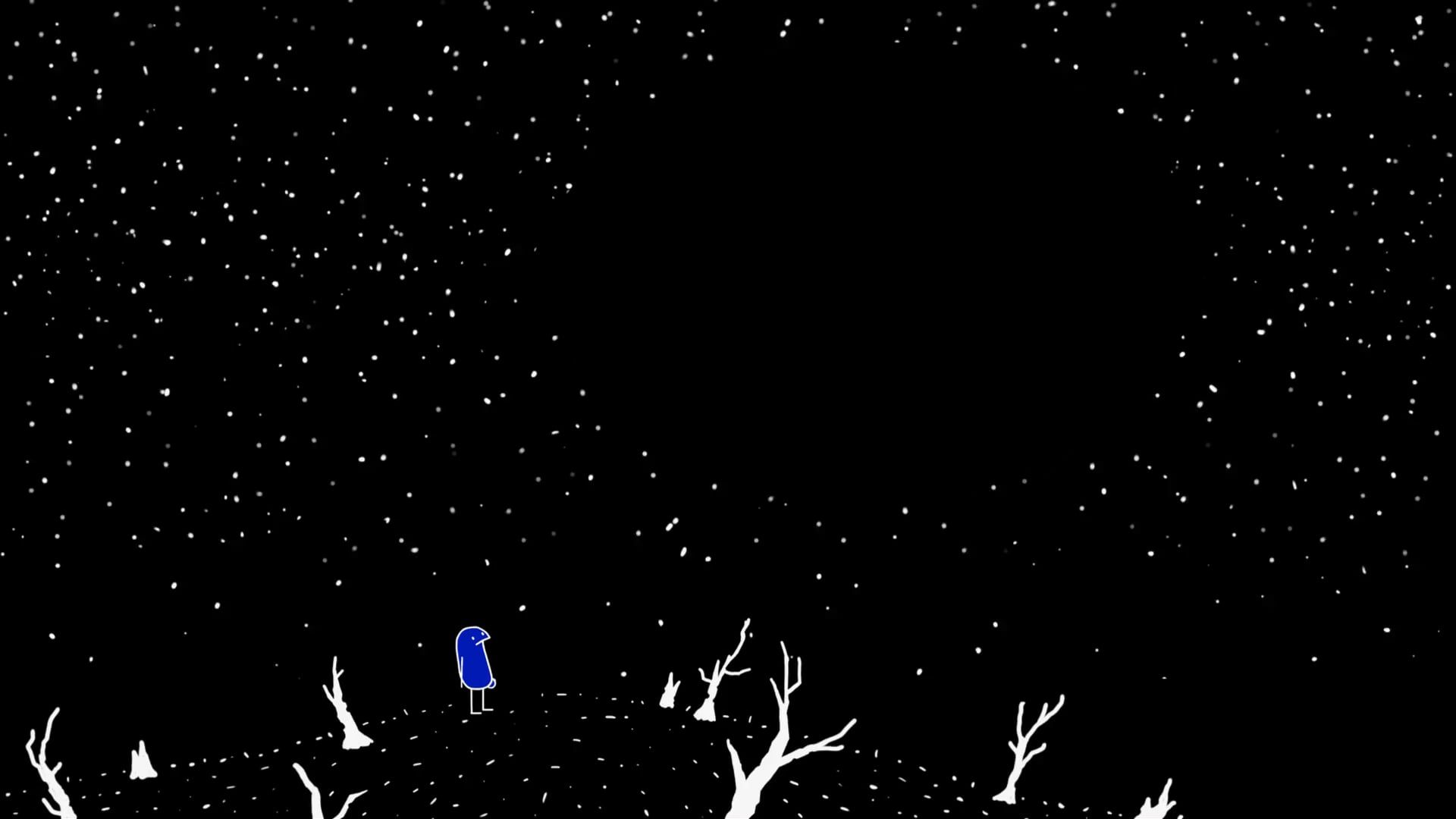

Case in point: the “ME” scene in which its self-absorbed dad uses his invention for the first time. Every Hertzfeldt image is a quintessentially Hertzfeldian image, but perhaps none more so than that of a simple little potato man staring agog at a vision of his younger self (or whatever), the single line that forms his mouth somehow betraying all the awe and terror of being alive. Frequently repeated in one form or another throughout the rest of this short, that moment crystallizes why so much of Hertzfeldt’s recent work seems to explode from a cosmic collision between nothing and everything all at once, just as it explains why these films keep stretching toward the stars as they probe deeper into the pit of our souls.

The first minutes of “ME” are as visceral and alive as anything Hertzfeldt has ever made, but they don’t give an accurate sense of how abstract the film’s story will soon become. Quite the opposite. Given the backstory of this project, and the bluntness of the band whose music it was allegedly made to reflect, the opening section of “ME” suggests that Hertzfelt’s latest short might not be able to escape the “put down your phone and live in the moment” ethos that his “World of Tomorrow” used as a springboard to reach its much richer conclusions (“now is the envy of all the dead”).

Then again, even this film’s most legible moments, like the wide shots of the self-obsessed Potato Man blithely walking past scenes of mass death as he thinks about his device, are textured in a way that pulls focus from the “how we live now” of it all and makes it impossible to reduce “ME” to some kind of finger-wagging PSA. Confetti-like “film” scratches combine with colorful frame tints and the percussive groove of an original Brent Lewis track to suggest the impression of an old silent film (“Metropolis” comes to mind on more than one occasion), and Hertzfeldt creates an electric friction by rubbing such retro flourishes against the surface of a story that’s hurtling into the future.

And “ME” does keep moving forward at breakneck speed, even as it starts running on a pair of parallel tracks that will send it careening away — sideways and then skywards — away from the world as we know it. This is where we enter what I think Hertzfeldt would consider “spoiler” territory, even if I’d argue this short defies the term (though I am about to describe everything else that happens in it). With a sudden injection of Mozart, the movie doubles back to see how the inventor’s potato wife reacted to her partner’s all-consuming obsession. She was pregnant, we learn, and not with a “normal” fetus (i.e. one shaped like an ambulatory spud), but instead with a giant eyeball.

As lovably unloveable as so many great Hertzfeldt characters before it (it’s so cute all snug in its bed at night, and while playing on the floor with the “i”s while its “normal” brother uses all the other alphabet blocks), the eyeball isn’t the bundle of joy the inventor’s neglected wife may have been hoping for. She wanted to be seen, but not so intensely. Not by an eyeball who starts defying gravity as it grows up (think more Nathan Fielder in “The Curse” than Elphaba in “Wicked”). The punchline of the cosmic joke is a lot harder to pin down than most of the other bits in Hertzfeldt’s recent work (in part because the “World of Tomorrow” movies were memory safaris complete with a roster of indelible tour guides), but I tend to think of it as an unblinking reminder of the reality at hand for Mrs. Peanut Person.

Hertzfeldt’s films repeatedly find that we can survive anything except the recognition that our lives — ugly as they might be — are unfolding before us in real-time. That thought becomes so hard for Mrs. Peanut to stomach that she eventually lets her eyeball baby float up into the heavens (the first in a series of crushingly sad tableaux), where it grows into godlike proportions and weeps over humanity as people become so addicted to her husband’s Zoom-like device that entire cities are reduced to giant electrical outlets.

Tension mounts between the past that people cannot escape and the present they’re unwilling to accept, eventually growing so taut that it snaps back together like an elastic band — tearing a fatal rift in the space-time continuum. Later, humanity’s (or peanut people’s) residual memories are fed into an anthropomorphic nervous system that absorbs the content of their iPhones à la “A Clockwork Orange” and then runs through a backdrop of primordial landscapes while bleeding from the neck and singing Joan Sutherland’s “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls.” The eyeball watches on as everything before it sprouts daisies and crumbles into stardust; the nervous system is the last thing to go. For a brief and beautiful moment, feeling is all that remains of what we were. Then again, Hertzfelt suggests with the latest in his ongoing series of small miracles, feeling is all that we could ever have hoped to be. What a shame it is that we keep wasting it on ourselves.

“ME” is now available to rent on Vimeo.