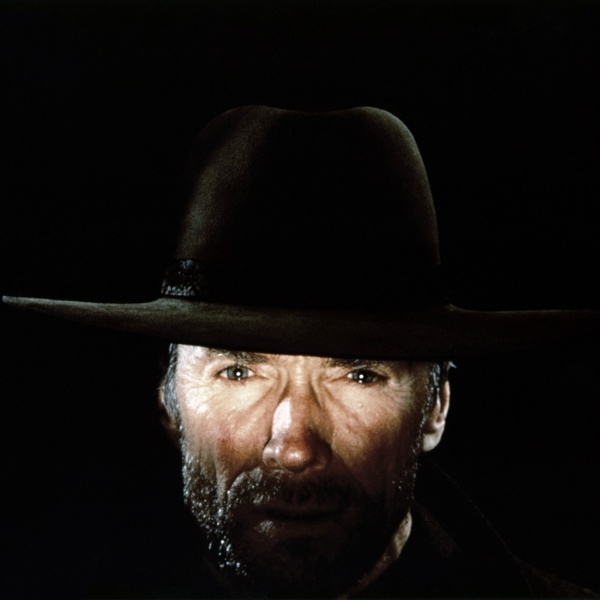

When Andrew Davis directed Chuck Norris in “Code of Silence” nearly 40 years ago, he established the template for the rest of his career: using the action genre to explore ideas he cared about.

In the case of “Code of Silence,” that meant a deep dive into Chicago racial tensions and the ethical complexities of police work. Davis’ skill at staging and shooting kinetic suspense grabbed audiences in that film and the terrific thrillers that followed, but what really separated him from his peers was the elegant integration of his own social conscience into the material. Whether the subject matter was the threat of nuclear proliferation in “The Package,” the CIA’s complicity in the international drug trade in “Above the Law” (Steven Seagal‘s first and easily best movie), or the moral and psychological cost of vengeance in “Collateral Damage,” Davis’ work has always been as thoughtful as it is dynamic.

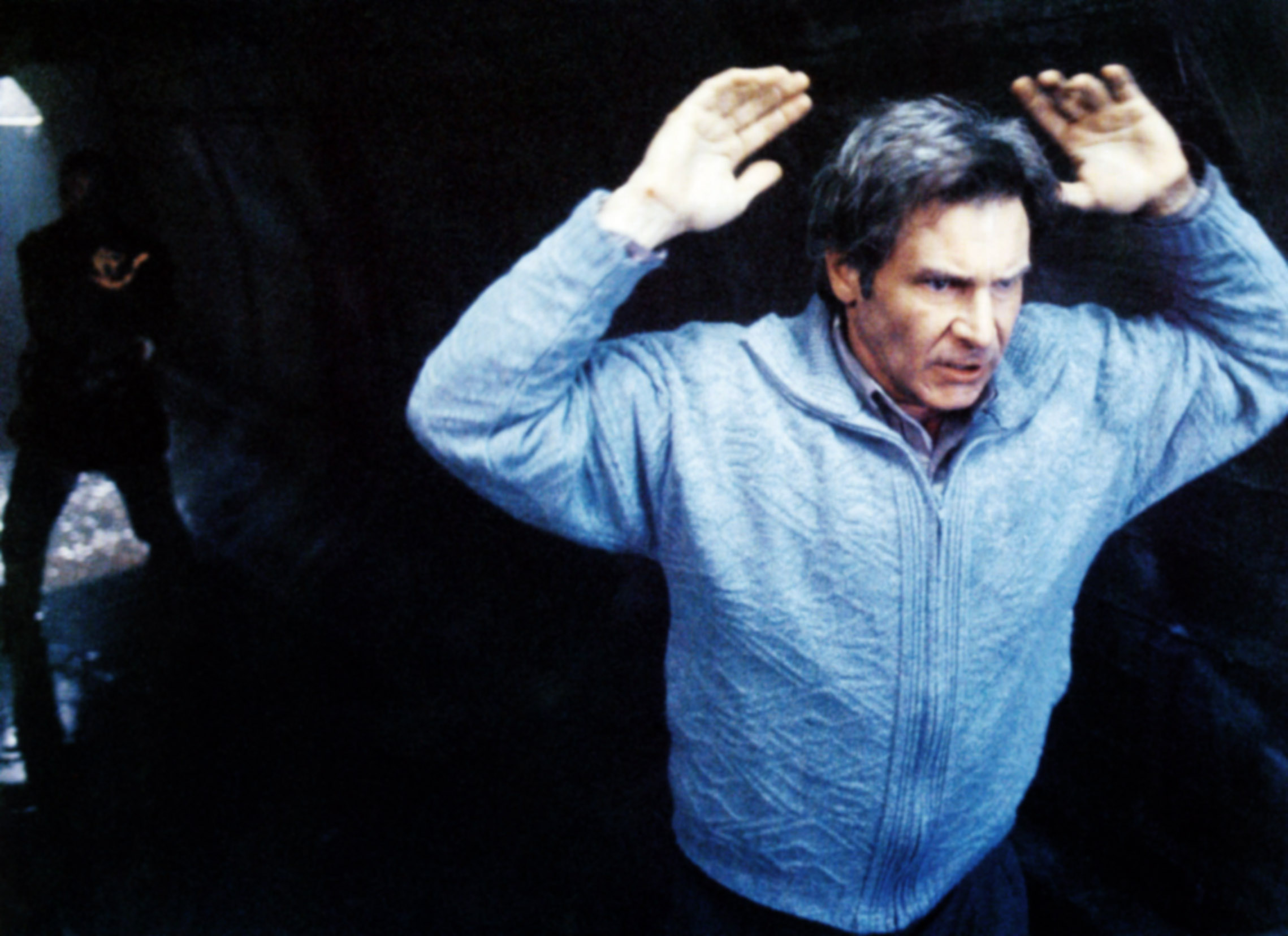

Now, Davis, best known for his 1993 classic “The Fugitive,” has a new story about the threat of nuclear catastrophe that’s as provocative and exciting as any of his previous work. This time, however, his manner of expression has taken a different form: “Disturbing the Bones,” a political thriller Davis wrote with Jeff Biggers, is a novel. “It started as a screenplay, but I got frustrated because I wanted to have so much backstory and texture,” Davis told IndieWire. “I kept wanting to add details.”

Indeed, one of the great pleasures of “Disturbing the Bones” — a complex weaving together of personal drama and global politics that examines the repercussions when the skeleton of a missing civil rights activist is found during an archaeological dig in Southern Illinois — is the wealth of detail that accumulates from page one and never lets up. Davis has always applied an adept journalistic eye to his material. The anthropological observations about how cops and criminals really operate in “Code of Silence” and “Above the Law” are what elevate those films so far above other films of their ilk. But co-writing a novel really enabled him to give those impulses free rein.

“The transition from writing it as a screenplay to writing it as a novel was very liberating because you could just write whatever you wanted,” Davis said. “We didn’t have to worry about everything being a minute per page, and we could explore deeper feelings.” Davis asked Biggers to collaborate with him after reading Biggers’ book “Reckoning at Eagle Creek,” which took place in the same part of Southern Illinois that Davis wanted to explore in “Disturbing the Bones,” an area with a history of racial unrest that the novel delves into with haunting power.

“I was in Santa Barbara, and Jeff was in Iowa, and we were on Zoom,” Davis said when explaining their writing process. “It was during COVID, and we would share drafts back and forth. It was very collaborative and wonderful.” Given that one of the lead characters is a veteran Chicago detective, it also allowed Davis to return, at least for large sections of the novel, to the city he loves and knows most deeply.

“I call Chicago my backlot,” Davis said. “It’s got incredible characters, real people that I’ve used in my movies, whether they’re cops or doctors or whatever — Dennis Farina was still a cop when he was in ‘Code of Silence.’ I understand the architecture, I understand the neighborhoods, so I don’t have to second-guess where to shoot. When I made ‘A Perfect Murder,’ I was really concerned that I didn’t know New York well enough. I had to feel it out and go into the Bronx and the different neighborhoods — the Upper West Side, the Upper East Side.”

In nearly all his films going back to “Stony Island,” Davis presents Chicago with both breadth and depth, giving a real sense of the city’s energy and people in a manner that no other filmmaker can really touch — he’s to Chicago what Scorsese and Spike Lee are to New York, or Paul Mazursky was to Los Angeles. His attention to anthropological detail not only gives his movies rich textures that reward repeat viewings, it gives his actors worlds to respond to that yield rich responses — actors as wide-ranging in their styles and talents as Andy Garcia, Tommy Lee Jones, and Steven Seagal have done their best work under Davis’s direction.

“On ‘Code of Silence,’ I surrounded Chuck Norris with real cops,” Davis said. “It made him relate to that world and fit into it. Same thing with Seagal. We surrounded him with real people — and real actors.”

Part of Davis’ striving for authenticity originates in his early ambition to become a journalist, not a filmmaker. “I was not a kid who read comics. I wanted to watch documentaries. I was interested in reality. And I found that, in doing action movies, you could talk about political things as long as the action was good. If someone was doing great martial arts, you could talk about Iran-contra, or cops covering up things or nuclear weapons.”

The irony is that Davis not only never intended to become an action director; he never intended to be a director period. “My intention was to become a cameraman,” he said. “I was a protégé of Haskell Wexler’s, but I had trouble getting into the union.” Davis and several now well-known cinematographers, including Caleb Deschanel and Tak Fujimoto, joined forces to sue the union, but the lawsuit took so long to wind its way through the courts that Davis decided it would be faster to become a director than a cinematographer.

“It was easier to get into the DGA than to become a cameraman!” Davis said. “I saw that Scorsese had done ‘Mean Streets’ and George Lucas did ‘American Graffiti,’ so I decided to do a film about where I grew up.”

That film, “Stony Island,” was a musical that led to Davis getting what should have been his big break on “Beat Street,” a project Harry Belafonte hired him to write and direct. When Belafonte ran behind on the music, Davis became the scapegoat and was fired after 15 days of shooting, but Orion executive Mike Medavoy saw the promise in Davis’s footage and offered him “Code of Silence.”

From that point forward, the die was cast: “Code of Silence” was a hit, and Davis would spend most of his career directing action films like “Under Siege” and “Chain Reaction,” with occasional detours into other genres like the children’s fantasy film “Holes” (which nevertheless contained a realistic and trenchant view of the juvenile detention system). “I feel really lucky that I was able to make these films,” Davis said. “‘The Fugitive’ has a lot of action, but it’s a very political movie, and it’s a very heartfelt movie.”

Writing “Disturbing the Bones” hasn’t quenched Davis’ desire to keep making political action films — in fact, he still hopes to turn it into a film as originally intended. “People who’ve read the book say it reads like a movie, and they ask, ‘When are you going to make it into a movie?’” Davis said. “The business has changed so much, but I hope I can make it — I’ve just got to find three really huge actors to get it made.”

“Disturbing the Bones” is now available from Melville House Publishing.