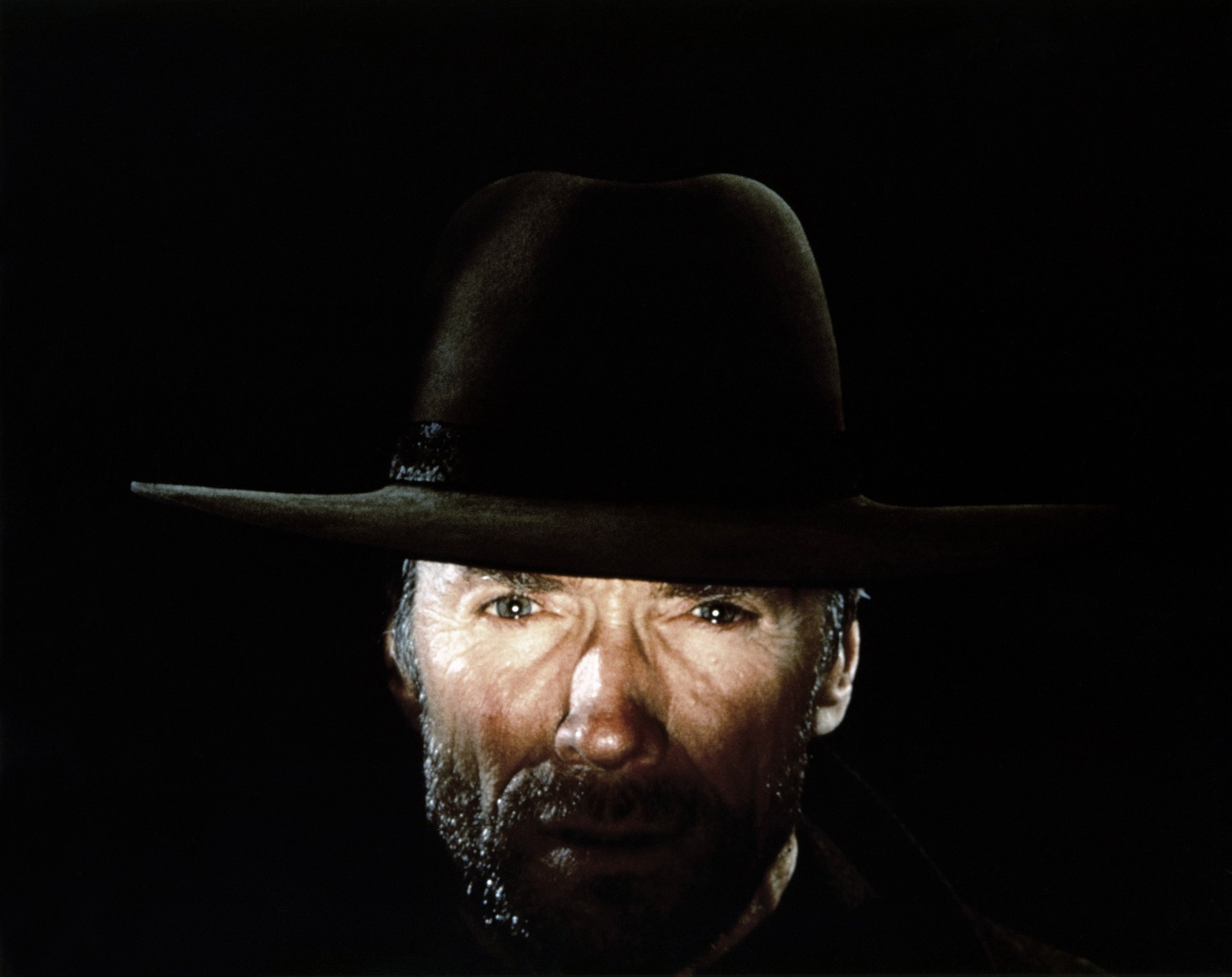

Why all the outrage over the apparent slighting of Clint Eastwood’s “Juror #2”? There’s the limited theatrical release, no advertising, and initial absence from Warner Bros. Discovery’s awards page, for a film with strong reviews and audience response — but good grief, has everyone at that studio forgotten what they owe Eastwood’s legacy?

The Warners-Eastwood relationship is unparalleled in Hollywood history. It also represents a way of doing business that Warners no longer cares to apply to its creative relationships — or at least, doesn’t care if that’s the community’s takeaway, which may be the same thing.

Since 1971, Eastwood made 46 films for Warners as a director and/or actor and/or producer (usually, more than one). IndieWire wants to make the case that Eastwood has been the most important creative component in the studio’s history — financially, and arguably, critically.

If that seems extreme, consider this. All told, his 46 Warners films have a worldwide gross, adjusted (as are all figures cited here) to 2024 values of over $9 billion. That’s before adding the massive take from all other platforms. (Eastwood’s total career gross is $12 billion; more than 75 percent belongs to Warners.)

That’s a lot of revenue, but the next figure makes it staggering: Production costs of amounted to around $2.7 billion. Promotion costs notwithstanding, that’s a 233 percent return on investment. Who else can claim that?

Eastwood’s track record includes 24 films that grossed over $100 million domestic, with nine over $200 million. While these numbers pale compared to, say, Steven Spielberg and James Cameron (although with much higher production costs), but those filmmakers worked across multiple studios.

Eight of Eastwood’s films ranked within the top 10 films for their year; the studio’s runners up are James Cagney (four) and Humphrey Bogart (two). Michael Curtiz (“Casablanca,” “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” “Captain Blood”) also has eight, but many were assignments as a contract director rather than overseen during all stages of production.

The gap between Eastwood’s first Warners blockbuster (“Dirty Harry” in 1971, directed by Don Siegel) and his last (“American Sniper,” the #1 domestic release of 2014) is 43 years. His films brought prestige as well as commercial success with two Oscar Best Picture Winners (“Unforgiven” in 1992, “Million Dollar Baby,” 2004). Eastwood-directed films also won seven Oscars in the best acting and directing categories for Warners, and within those years accounted for most of the studios’ wins.

Five of his films as director competed for the Palme d’Or in Cannes, virtually unheard of for an American studio director. (Spielberg’s films, when shown, have mostly been out of competition). Add all the other awards accrued by Eastwood’s films and no one else at Warners is remotely close. (One that has eluded him is the SAG-AFTRA Lifetime Achievement, which would seem justified at this point.)

Although he chooses to operate on tight budgets, his films star actors in peak demand including Kevin Costner, Meryl Streep, Kevin Spacey, Sean Penn, Angelina Jolie, Matt Damon, Leonard DiCaprio, Sandra Bullock, Bradley Cooper, and Tom Hanks.

Perhaps as significant as any achievement is how it allowed Warners to uniquely represent itself as a stable studio founded on relationships. That required patience.

In the late ’80s-early ’90s he made money-losing films like “Pink Cadillac and the acclaimed biopic “Bird.” He rebounded with “Unforgiven” and a stretch of major hits soon after. Before “Mystic River” and “Million Dollar Baby” there were “True Crime” and “Blood Work.” Later, both “Gran Torino” and “American Sniper” were massive successes. “The Mule” in 2018 grossed over $200 million worldwide, around four times its budget. And if “Cry Macho,” his last film before “Juror #2” carried a loss, its release during the late stages of Covid with a same-day Max streaming release hardly proved his lack of appeal.

In theory, Warners can argue that it was the right short-term financial decision to prioritize Max for “Juror #2” (Warners claims this was always the plan, although the first public mention came two months ago). However, that theory falls apart in the context of what he has meant for the studio and as a symbol of continuity and respect.

It’s all about legacy. Eastwood’s is secure, with or without appropriate treatment by Warners. Perhaps David Zaslav, CEO of Warner Bros. Division, should be more concerned about his as well.