Robert Eggers’ spectacular “Nosferatu” opens with several pronounced seconds of perfect, crypt-like blackness, as if the director were adjusting his audience’s eyes to see in the dark. But the film that follows — luminously ashen where too many recent movies and TV shows have just been irritatingly dim — is flooded with a moonlight so lucid and alive that even the story’s most stygian moments might as well have been set at high noon. For all of its exquisite darkness, this “Nosferatu” is never the least bit difficult to see.

The reason for that is simple: Eggers doesn’t want us to see in the darkness, he wants us to see the darkness itself. To recognize it not as the absence of light, but rather as a feral and undying force all its own — one that we carry within ourselves like a secret corseted in virtue.

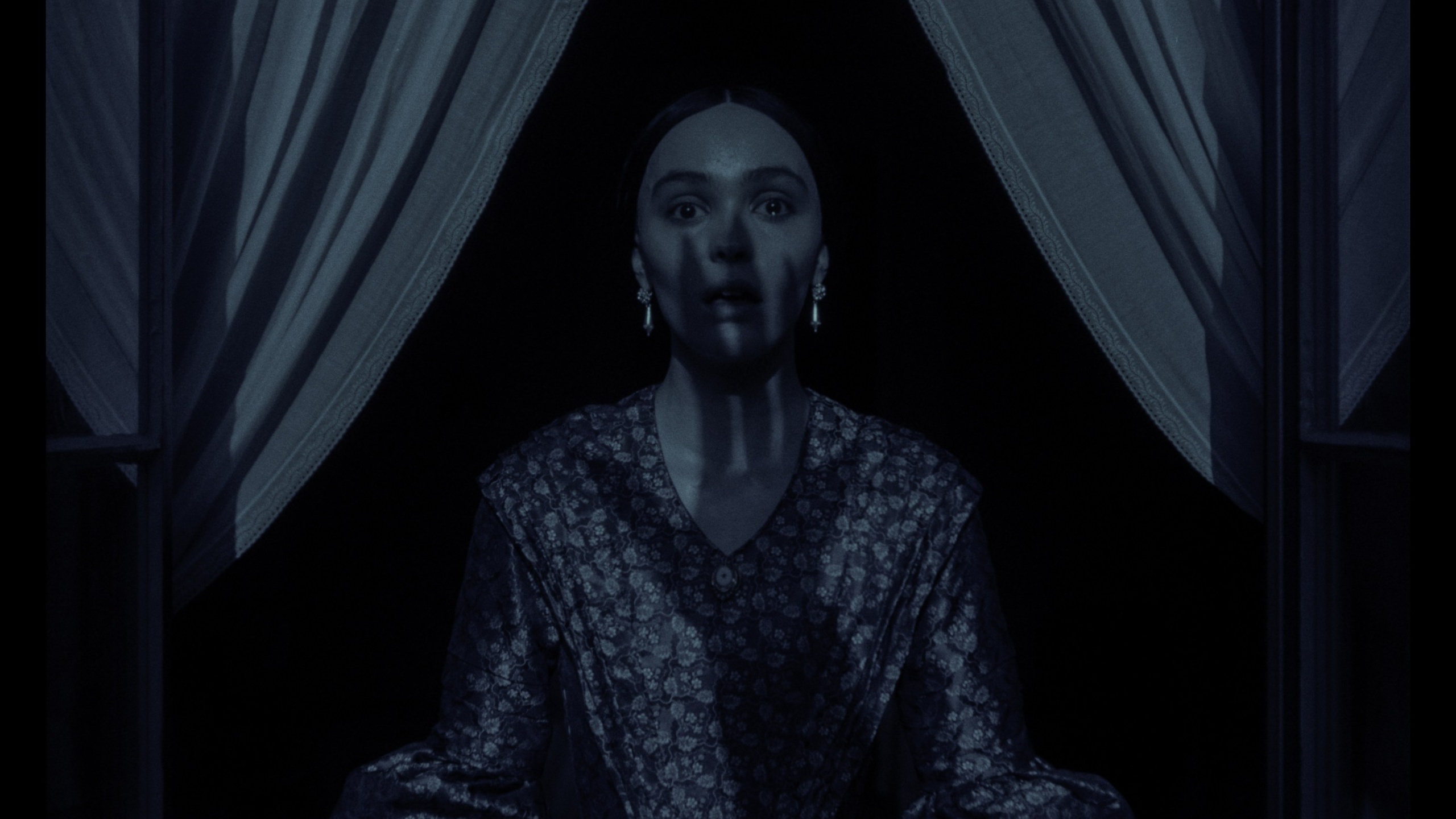

Faithful as it might seem to F.W. Murnau’s 1922 “Nosferatu,” Eggers’ lush and rapturously psychosexual riff on the same material isn’t a simple remake so much as a seductive reverse shot. Where the earlier film climaxes by casting the silhouette of a vampire against a solid wall, this new one starts by projecting the same image across the soft white curtains of its heroine’s bedroom window, as young Ellen Hutter’s (Lily-Rose Depp) midnight prayer for “a spirit of comfort” is answered by a hunger so close at hand that its appetite seems to be rooted within her own heart.

Or perhaps the call is emanating from somewhere else in her body, as Ellen comes to the voice as much as it comes to her. The prologue might end with a paroxysm of violence, but first there are a few timid whimpers of nascent pleasure; Bill Skarsgård’s base and primal Count Orlok is a nightmare who arrives on the wings of a nocturnal emission. Despite Orlok’s prosthetic decrepitude and the plague-like toxicity of his love, what truly horrifies Ellen about him is that some unknown part of her nature craves his touch.

Ellen’s special friend will come to assume increasingly corporeal form as the movie goes on, and Eggers won’t be able to stop himself from paying more literal homage to Murnau’s most famous shot by the time it’s over, but it’s the human woman — not the slumbering monstrosity she awakens from afar — whose silhouette will consume this film’s attention. As compelled by the fear of the self as Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” (and Murnau’s unauthorized adaptation of it) was by the fear of the other, this Jungian twist on theformative vampire story keeps its villain shrouded in shade in order to illustrate how its heroine is merely shrouded in light; she’s a living shadow play whose true curse is belonging to a pre-Victorian society that sees female desire as its own form of darkness. Ellen’s only salvation, such as it is, is that she was born into a “Nosferatu” capable of seeing her darkness so clearly.

Modern in its perspective yet fetishistically accurate to its time, Eggers’ horny-as-hell but highly repressed “Nosferatu” is nothing if not the version of this story you would expect him to make. Like “The Witch” before it, the film renders sin with a puritanical sense of mortal danger. Like “The Northman,” this ultra-sincere “Nosferatu” is a stylized fable that shirks off the simplicity of its plot with a visceral physicality. Like “The Lighthouse,” it features a deliriously happy Willem Dafoe as a pipe-smoking kook who says things like “The night demon has supped your good wife’s blood” with the enthusiasm of a character all too happy to have that chance. And like all of Eggers’ films, of which “Nosferatu” is the richest and most fully realized, it draws a spellbinding power from the friction it finds between historical social mores and the eternal human thirsts they exist to keep in check.

If “Nosferatu” sinks its fangs a tiny bit deeper than any of the director’s previous work, perhaps that’s because it’s tinged with a degree of tragic cruelty that Eggers has yet to allow in his “original” material. In stark contrast to the settler heroine of “The Witch,” who takes at least some joy in accepting the devil’s bargain to live deliciously, Ellen yearns to find her peace within the patriarchy. Her first thought after signing a covenant with Orlok’s disembodied voice isn’t to seek out his crypt across the Carpathian Mountains, but rather to settle down with the most basic man in Wisborg, Germany circa 1838: middle-class estate agent Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult), a handsome nobody whose cheekbones are higher than his wages.

Ellen hopes that marrying Thomas will stop Orlok from calling out to her in the night, but her dear husband is equally seducible to his own simplest instincts. It’s Thomas whose ambition leads the vampire right to the Hutters’ front door, as his new boss — the bestial Herr Knock, played by a scenery and cast-chewing Simon McBurney — tasks him with journeying to Transylvania in order to finalize a real estate deal with a mysterious count from “an eccentric bloodline.” Providence? Ellen is the only person who seems to know better. “But he already has the job,” she whispers to the heavens after learning of Thomas’ audition-like first assignment, a throwaway moment that speaks volumes to what’s said and unsaid in their relationship.

On the subject of that relationship, all we really know about it is that Ellen and Thomas seem to genuinely love each other — and that the children they intend to have one day would be born with jawlines sharper than any stake. There’s never any reason to think that a better husband would solve Ellen’s problems, in part because they share a palpably mutual attraction, even going so far as to make out on the floor of their rich friends’ mansion after a dinner party one evening (which seems like some pretty egregious PDA for the time period). Not that shipping magnate Friedrich Harding (a fantastically imperious Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and his wife Anna (Emma Corrin) would think twice if they caught their houseguests snogging in semi-public; Friedrich is a “rutting goat” of a man, and Anna seems to have accepted a nearly permanent state of pregnancy as the only affordable price for her pleasure.

Ellen has a more complicated relationship with her unarticulated lust, which is really just the expression of all that she wants but lacks permission to ask from life. Eggers’ broadly suggestive script doesn’t put too fine a point on the specifics of Ellen’s repression (she identifies Orlok as the manifestation of her shame, and insists that she has no need for salvation), but Depp’s revelatory performance ensures that the rest of the movie doesn’t have to.

Pouty but headstrong, possessed but clinging to what’s left of her power, Depp plays Ellen as a young woman so at war with the foreignness of her own unconscious that at one point her tongue threatens to detach itself from the rest of her face, as though the muscles of her body were attempting to escape through her mouth. Orlok’s influence overcomes Ellen in a series of Butoh-inspired seizures equal parts Linda Blair and Kazuo Ôno, and there’s no small irony to the remarkable self-control Depp has to display in order to so convincingly wrestle with her character’s darkness, which concentrates inside of the poor newlywed like a blood clot.

Alas, Baltic Germany’s medical establishment (embodied here by Ralph Ineson’s Dr. Wilhelm Sievers) only knows to treat repression with repression. At one point he prescribes his increasingly “hysterical” patient an even tighter sleeping corset, as though a few bits of firm lace might be enough to suffocate the devil inside of her. Dafoe’s Professor Albin Eberhart Von Franz has other, more progressive ideas, but his stranger methods trend more towards the occult than they do to modernity.

And what good would modernity really do for a woman whose lifeforce so violently chafes against patriarchal control? Needless to say, Orlok will make the trip to Wisborg — arriving in Germany like a plague, with Thomas all but crawling back home to his wife behind him — long before Western society will learn to accept that denying human desire is less a collective victory than a personal self-defeat.

There isn’t time enough for that to happen in this movie, though Eggers certainly holds out for as long as he can. The filmmaker smears this wet pinprick of a story across 132 lavishly illustrated minutes, its plot spread thin but its atmosphere suffused with fresh details. Like any great fairy tale, “Nosferatu” demands a certain degree of surrender. Like too few of the films adapted from them, it earns that surrender with the strength of its craft.

The morbidly enchanting sequence where Hutter arrives at the foot of Orlok’s castle — the weary traveler rescued by a self-driving carriage — is the best kind of indulgence, as Jarin Blaschke’s ultra-desaturated 35mm cinematography steeps us in the pallid splendor of this twilight world until death itself seems like a beauty worth savoring. I don’t get the impression that Eggers is much of a gamer, but few movies have ever come so close to capturing the feel of “Bloodborne” on the big screen.

Wisborg isn’t especially vast, but the four city blocks that Eggers’ team created on a Prague soundstage are as evocative as a snow globe, and only seem to become more so whenever Ellen begins to shake. Eggers allows himself a handful of conventional horror scenes, but all of them — save for a few tedious bits highlighting Knock’s use to Orlok, and a “Last Voyage of the Demeter” sequence that’s short on fresh ideas — are enhanced by their extraordinary manipulation of shadow, which elevates standard jolts into a vivid dance between id and ego. (I can’t remember the last time a fake-out scare was so rewarding.)

There’s hardly a millisecond of this movie that isn’t measuring the distance between people and the darkness they disavow within themselves, an effect so palpable that Orlok himself comes to feel somewhat irrelevant to the story he sets into motion.

Eggers certainly loves the guy, and Skarsgård’s ultra-committed performance allows the film to enjoy a contagious pleasure in returning the vampire archetype to its more bestial origins. It also allows Eggers’ “Nosferatu” — a film more interested in psychic anxiety than sociopolitical prejudice — to untether its vampire from the anti-semitic tropes that Murnau’s version was forced to contend with. This Orlok is a more carnal force than ever before (it’s rare that we get to see Dracula’s flaccid dick), but whatever sex appeal his raw animalism and thick mustache might hold for certain audiences is offset by rotting back flesh and a general rejection of aristocratic charm. If the makeup is impressive, Skarsgård’s undead baritone is what most brings the undead character to life, his every word of dialogue sounding as though it’s just been rolled across the river Styx.

If Skarsgård doesn’t make the same impression as Max Schreck, that’s largely because Eggers’ adaptation doesn’t give him much of a chance to emerge from the periphery. While reducing Orlok to an appetite is what allows “Nosferatu” to focus its energy on Ellen, the vampire is such a fantastic representation of Mrs. Hutter’s shadow that he struggles to take shape in her absence. Of course, that’s not the fatal flaw it might seem — not in a film so wholly enthralled by the question of where “evil” comes from, nor one so gloriously capable of illustrating why feeding our darkness is the best method we have of bringing it to light.

Grade: A-

Focus Features will release “Nosferatu” in theaters on Christmas Day.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings — all only available to subscribers.