It’s an inconvenient reality of modern existence that we seldom have the bandwidth to devote sincere attention to more than one humanitarian crisis at a time. Just like Afghanistan gave way to Ukraine which gave way to Gaza, it won’t be long before another unspeakable human tragedy absorbs the limited amount of minutes in each day that we’re able to allocate to international news. (The demands of our time and compassion can be so numerous that we still haven’t gotten around to the Uyghurs, despite the fact that they’re long overdue for a cycle in the atrocity spotlight.) All but the most saintlike among us have been guilty of prioritizing a shiny new human rights violation at the expense of an ongoing one, but that doesn’t mean that things magically improve once our attention drifts away. Oftentimes, that’s when things really start to get ugly.

Years have passed since the Syrian refugee crisis was a trendy thing to talk about, but the distractions created by our lightning fast world haven’t dulled the painful challenges that millions of displaced Syrians face each day. The brutal civil war that began in 2011 as Bashar al-Assad cracked down on protests by using chemical weapons on his own people has displaced over 15 million Syrian citizens over the past decade, many of whom settled in Europe. Coverage of refugees often focuses on the challenges that European countries face while trying to accommodate them, effectively ensuring that their stories end once they cross the border in the eyes of many news consumers.

“Ghost Trail” is a film that refuses to let anyone treat the plight of Syrians like a thing of the past, or to delude themselves into thinking that the war ends once Syrians are relocated to safer countries. Set around the border of France and Germany, Jonathan Millet’s directorial debut follows a group of Syrians living in Europe who look for jobs by day while plotting to settle unfinished business by night. Because as we quickly learn, not everyone who flees Syria for Europe is innocent.

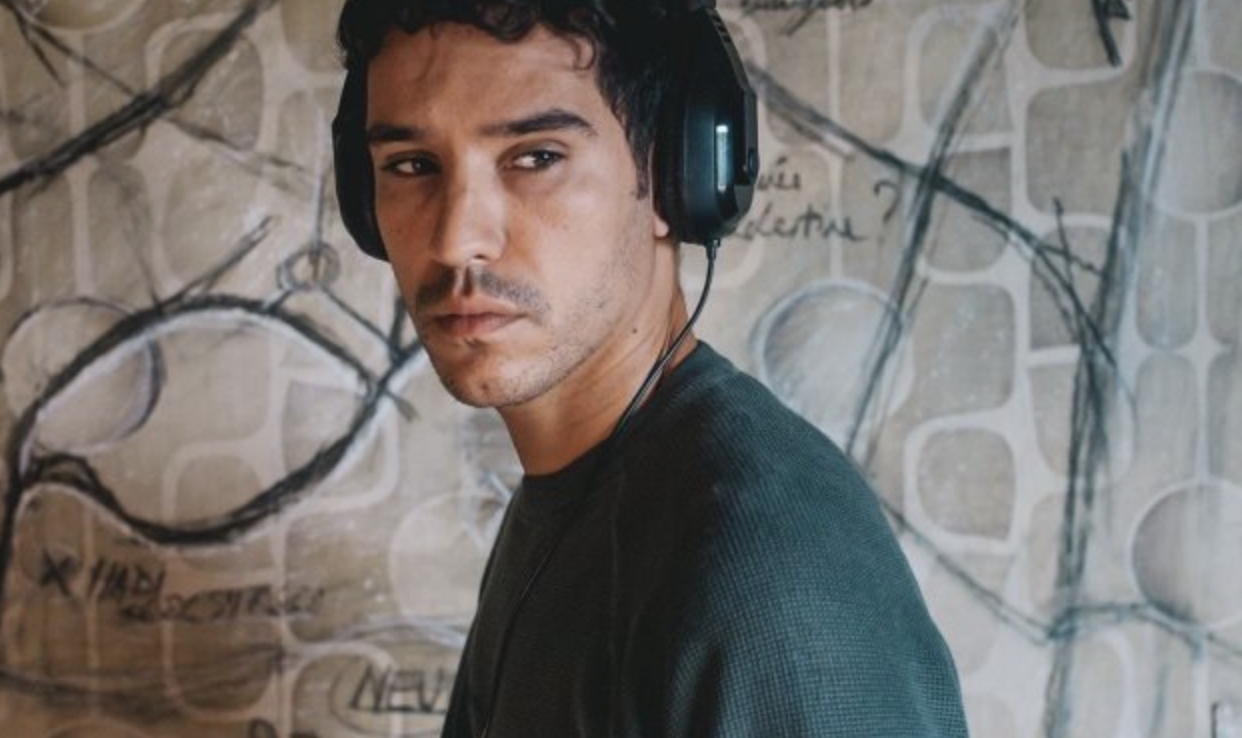

When we first meet Hamid (Adam Bessa), he doesn’t have many means of remembering the life that he left behind. His wife and daughter both died brutal deaths during the war, and he never had a chance to see their bodies or hold a funeral. Now that he has resettled in Strasbourg, France, his only remnants of home are FaceTiming with his mother and eating at the occasional Lebanese restaurant. But while he might present himself as the media stereotype of a refugee, drifting aimlessly in a land he doesn’t belong in, he’s actually a man on a mission. Each evening he logs onto a server and plays a war video game with an underground network of Syrians who are spread across Europe. Their goal? To track down all of the Assad loyalists who fled to Europe after committing war crimes and bring them to justice.

The game’s violent contents allow them to discuss bombings and weaponry without being flagged by algorithms, so they use the multiplayer setting as a forum to lay out their plans. Hamid is dead set on tracking down a man named Harfaz, now living in Strasbourg under the alias Sami Hana, a man who brutally tortured him and his loved ones during the war. Hamid believes that he has found his target, and spends days slowly following the man at a distance through a series of cafes and libraries.

Despite being vigilantes, Hamid’s co-conspirators take a surprisingly thorough approach to due process. They forbid him from acting on his anger until they have indisputable proof that Sami Hana is their man, so he is forced to acquire photos of the man and show them to other Syrians who can corroborate the accusations before bringing him down. But every day that he spends stalking the man simultaneously brings him closer to justice and further from taking the productive steps that could help him move on with his life.

Before becoming a filmmaker, Millet spent years traveling to third world countries as a stock footage photographer who documented the impacts of war and poverty. The on-the-ground training is clearly paying dividends, as “Ghost Trail” is filled with beautiful shots that demonstrate how you don’t need a single word to illustrate the pain in a human soul. Bessa embodies Hamid with the tragic emptiness of a man who is unable to properly grieve his losses while being forced to reinvent himself in an unfamiliar world every day. Their combined efforts allow the film to marry some of the best aspects of spy thrillers and slow cinema in a portrait of the ways that wars haunt us long after we escape them.

If there’s a downside to the film, it’s that Hamid’s plan is so comprehensive and well-executed that the conclusion starts to feel inevitable very quickly. But it could just as easily be argued that the slow march to an obvious destination is part of the point. “Everyone talks about our country, the death, the problems,” Harfaz tells Hamid at one point. “You can’t start a new life if you waste your time dwelling on the past.”

There’s some truth to what he says, even if it hurts to agree with a war criminal. But what he fails to recognize is what Millet ultimately devotes his film to exploring: When everything you care about is taken from you, superficial opportunities to forge a new life don’t mean much. Your inability to bury your ghosts and capitalize on those opportunities is often just another casualty of the war.

Grade: B+

“Ghost Trail” premiered at the 2024 Cannes Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.