The Duplasses are starting miniature with their first full-fledged family affair on all sides of the camera: the short film “Oh, Christmas Tree,” a bittersweet 10-minute ode to a father and daughter reliving their favorite holiday traditions.

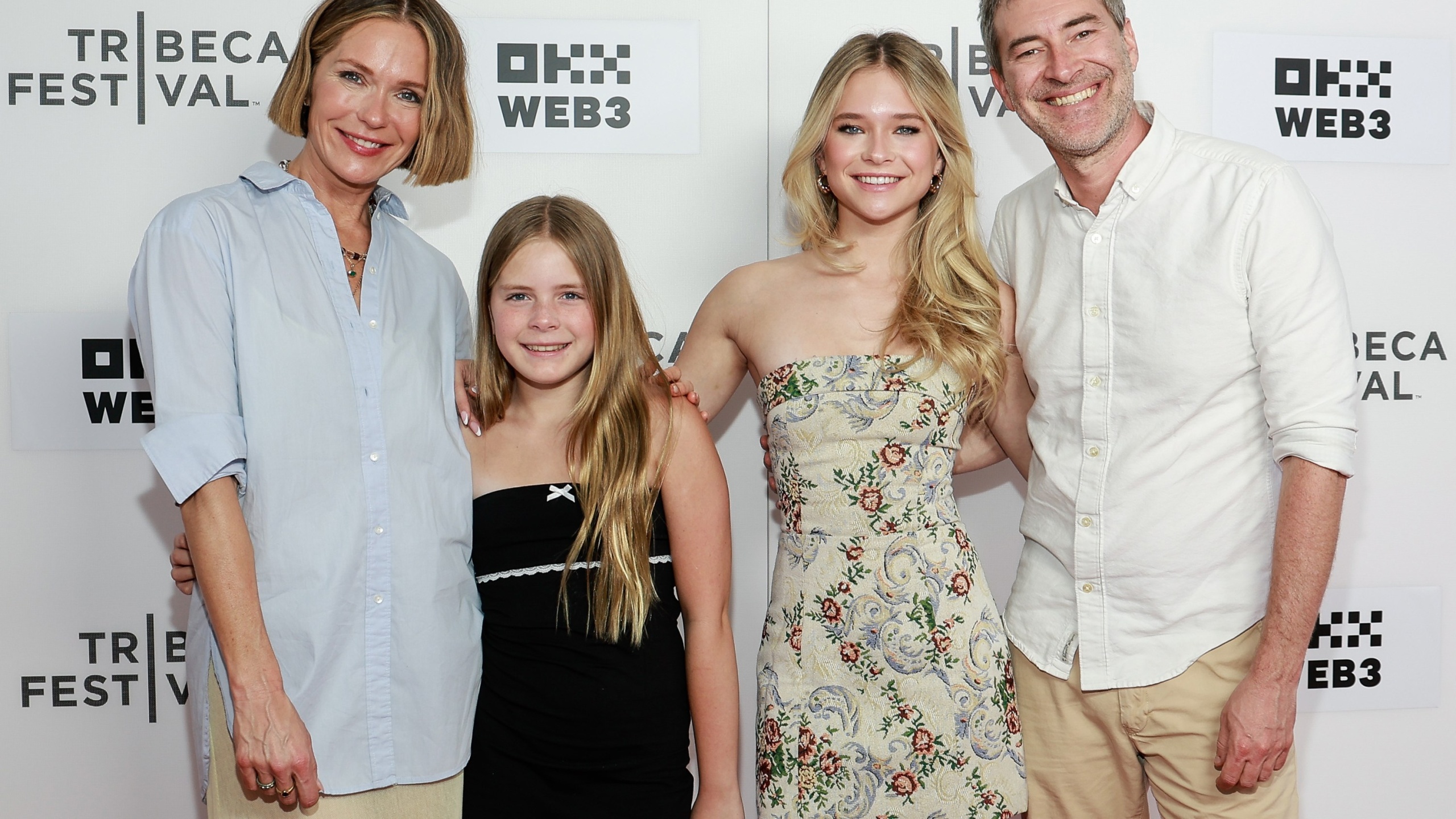

It’s written by Mark Duplass, directed by his wife Katie Aselton (“Mack and Rita“), and stars their 16-year-old daughter Ora opposite her dad in roles that aren’t exactly autobiographical despite the onscreen, lived-in rapport. Here, the mother is dead, and the daughter, Claire, is now the one doing the parenting as her father grapples with mental health struggles. The short, currently seeking buyers out of Tribeca Festival, packs a lot into its brief running time, and for this trio, it also marks Ora’s entry into filmmaking as she readies to follow in her parents’ footsteps. (Meanwhile, at Tribeca, the Duplass brothers also back football star turned filmmaker Nnamdi Asomugha’s thriller “The Knife” and Morrisa Maltz’s “Unknown Country” follow-up “Jazzy,” with Lily Gladstone.)

“Oh, Christmas Tree” is close to home in other ways: The Duplass family brain factory shot the film outside their cabin in Mt. Baldy, the glorious San Gabriel Mountain community about an hour’s drive northeast of Los Angeles. “We haven’t written there or hiked there, but we have shot a movie there,” Aselton said, laughing, while sitting down with Mark and Ora for an IndieWire chat at Tribeca at the Ludlow Hotel in New York.

“The independent Duplass filmmaking model is that every time we own a piece of real estate, we have to write a movie for it because that’s the cheapest way to do things,” Mark said.

And Duplass, the tireless director/writer/producer/actor known to many for his starring role in “The Morning Show,” himself has been candid over the years about his own struggles with depression and anxiety. “It’s really hard for me to find the line between being strong and telling my children, ‘It’s OK, you make your way in the world, your parents are strong, we’re going to hold you,’ but at the same time, express the vulnerability so that you’re a human as well,” Mark said. This short film does that and more.

Meanwhile, this isn’t Ora’s first experience on a Duplass project. She provided voiceovers for “Transparent,” starring her uncle Jay Duplass, sang over the credits for the Duplass-created HBO series “Room 104,” and otherwise spent time “eating craft services on the sets and preparing [my parents] for auditions. None of it has been in front of the camera until now … this is the launching pad.”

“To be honest, we were like, ‘Don’t be a child actor,’” recalled Mark of early advice they gave Ora, whom her parents brought up on all kinds of movies, from themed pandemic viewings of “Cast Away” to “The Money Pit” while in lockdown in Los Angeles. “We were like, ‘Fuck no.’ If there’s one way to break your spirit or be a damaged soul, this is the way to do it.”

“You know what damages your soul? High school!” Aselton said. “Hollywood is safer than high school. I watched ‘Quiet on Set’ and was like, ‘You’re right! Maybe you shouldn’t do that!’” She said that if Ora wanted to break in, “We’re going to do it and on our terms, and safely, and show you how it should feel… I’m happy to show her that you don’t have to wait for Universal, Warner Bros. to pick you, to give you permission to act. Find your talented friends, your people, pick up a camera, make something, and maybe no one will see it. Make something again, and maybe a couple people will see it… Just keep creating.”

That’s very much the guiding principle of the whole Duplass ethos, as brothers Mark and Jay founded Duplass Brothers Productions in 1996 and eventually helped legitimize the mumblecore movement with the microbudget “The Puffy Chair” (2005), made with $15,000 they borrowed from their parents and shot on a digital camcorder before earning the Audience Award and distribution from Roadside Attractions and Netflix out of the Sundance Film Festival. Together, they’ve produced, directed, starred in, and written dozens of indie films and TV shows since.

“[‘Oh, Christmas Tree’] really just allowed me to see this is what I’m meant to be doing,” said Ora, anticipating the usual questions about the inherent advantages of growing up with industry parents. “My one fear with this is just that people are going to think, ‘Yeah, she’s piggybacking off of her parents.’ ‘This is nepotism,’ whatever. But I think it’s more of just having this safe place to start.”

Almost two years after a New York Magazine piece that brought the term into modern parlance and with much scrutiny, the Hollywood environment is becoming perhaps more hospitable to nepo babies. Stars like Maya Hawke, who recently starred in her director father Ethan Hawke’s “Wildcat,” are beginning to own it.

“The nepo babies are having to prove themselves. The ones with no talent fall away, and that’s fine,” Aselton said. “I moved to Los Angeles when I was 19 and knew no one. Having to build this on your own is so hard.”

There’s a lot of Sturm und Drang right now about a stressed time for the industry, from festivals struggling to indies on the hook for distributors to withering box office numbers as consumer behaviors change. So why send their daughter into an industry that’s starting to feel like the beginnings of an abyss?

“I’ve been in this industry for 20 years, and I’ve experienced many versions of the cratering of the industry,” Mark said. “I’m not as alarmist as some, like, ‘Oh my god, it’s all over, it’s doom and gloom.’ I remember coming up at Sundance in 2005 and the run then was you make an independent film, and then you got Focus Features or Fox Searchlight, and that business dried up right when I arrived. And everyone was like, ‘It’s cratering, it’s over.’ I was like, ‘Well, I’ll just pivot, like I’ve always done.’ Then I moved into TV, and that was exciting for a while. Then premium TV started to dry up and crater, so I started to make independent TV… My philosophy has always been that independent filmmaking success has never been an easy or welcoming prospect. It has always been: You must destroy yourself in some shape or form to get there.”

Mark suggests we look outside the weekly box office tallies to find hope in dire times: Rookie streamers reaped big at Cannes, and repertory theaters from New York to Los Angeles are thriving.

“I don’t really think we’re in a place where it’s going to be easy for people coming up, but at the same time, there’s always going to be some sort of path. There’s always going to be some sort of way to make your way in… As our streaming business has died down, we’re going to see little bits of light. Like, here comes MUBI. Wow, Steve Rales just bought Criterion. That’s going to happen. This movie theater is starting to distribute things! Wait, nobody’s going to the movies? The repertory theaters! In LA, Vidiots is selling out 250 seats to see ‘The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant.’ We just got to find our way.”

And young people like Ora are catching on to the mixed bag of goods on offer at multiplexes.

Ora added, “I’ll go to movies with my friends, and we’re just like, ‘What have movies become? What are we watching right now?’ Then we go to Vidiots and watch an old movie and we’re like, ‘This is what film is. This is what we want to be seeing. I hate what this has become. With the drought of good filmmaking and creativity … comes the hunger [for] it.”

“Then you get Sean Baker winning Cannes,” Aselton said. “It’s not ‘Megalopolis.’ We have to get back to our core.”

Facing an even choppier upstream swim against the changing tides of industry are short films, which can live and die by a film festival when not propelled into awards season. Mark Duplass has a unique theory about how industry hubris can actually benefit a short film’s life cycle.

He noted that 20 years ago, there were only a few stalwart distributors of short films, including Atom Films, defunct as of 2012. “Since ‘Oh, Christmas Tree’ has come out, people are like, ‘Well, no one knows anything about distribution anymore.’ So maybe we should try this. We talked to Netflix, Apple, Condé Nast. There’s a version of this where people are seeing… everybody is very, very hungry for awards nominations, because it elevates them. So that tally — we got the most Emmy nominations! we got the most Academy Award nominations! — they’re starting to realize the short film category is one we can compete in with fewer dollars and still get our tally up.”

“No one’s looking at what categories,” Aselton said.

“There’s weirdly been this interest in making a run with ‘Oh, Christmas Tree’ and this storyline, so there’s potential partnership with that,” Mark said.

“With a short, it’s never about the sale. You’re just about getting out there and meeting people and seeing your great movies,” Aselton said.

Elsewhere up for sale under the Duplass shingle, Mark and director Patrick Brice have spun their “Creep” and “Creep 2” found-footage horror IP into an episodic series called “The Creep Tapes.” Like the films, the series stars Mark as a socially uncomfortable serial killer who hires victims to shoot him for a day.

Having worked on streaming series from “Evil Genius” to “Wild Wild Country,” Duplass is no stranger to how word-of-mouth can make a series when there’s not full-force promotion on the streamer’s end. Nowadays, premiering a streaming series is like dropping a stone down a well. You hope it resonates. And then, sometimes, you get a “Baby Reindeer,” Netflix’s wildly popular British limited series.

Most recently, Duplass and Mel Eslyn sold their indie series “Penelope” out of Sundance to Netflix — one of the streamer’s few Park City acquisitions. “That felt like a really big breakthrough because I’m trying to encourage these streamers and distributors who are used to [the idea that] the job of an executive creatively is [just] to develop this material. In some way, that same executive, if you bring them the thing finished, they think, ‘If you just buy this, you have negated my job.’ I totally disagree with that,” Mark said. “You should make those things, curate them, but at the same time, they’re making fewer and fewer things because the money is coming down. I can come to you and offer you something cheaply that satisfies what I call the ‘interesting middle’ that’s going away in TV. I’m hoping to make a model out of this.”

As for how a series can rise on streaming platforms glutted with content, Mark Duplass said, “There is some data out there, and I’m not saying that I believe in this, that [says] if you are a massive streaming service like Max, Netflix, whether you promote or not, the cream will rise to the top. So there’s an argument that … I might be able to promote a B+ show to a place that it goes viral, but if I don’t promote, it doesn’t matter, because all the A shows are going to rise.”

“I don’t believe in that for Apple, which is a premium thing, where you have to pull an audience,” Aselton said, referring to how Apple’s push for subscribers (Apple TV+ an estimated 25 million as of this spring) is more of an albatross than, say, for Netflix, which has around 270 million globally.”

“Netflix did not promote ‘Wild Wild Country.’ They just dropped it, and then everybody found it. They did the same thing with ‘Baby Reindeer’ and ‘Squid Game.’ They unfortunately have data that says we don’t have to promote, so we’re in a little bit of dicey territory. But the good news for ‘The Creep Tapes’ is that’s pretty organic. It’s based on IP that already exists. It’s immensely popular. You put one clip on TikTok and it just blows up. This one’s an easier call, I think.”

“Oh, Christmas Tree” premiered at the 2024 Tribeca Festival and is currently seeking distribution.