[This article was originally published in 2017. It has been updated in August 2024.]

70mm is back! Thanks to Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, and Christopher Nolan, one of the oldest and grandest traditions in Hollywood is making a comeback after years of financial setbacks and near-extinction. As Nolan has said many times, shooting in 70mm proved an immersive and more textured experience than any other form of cinema (side note: The 70mm film process actually uses 65mm film stock, which is printed onto 70mm film for projection purposes).

Due to the costly nature of film and theaters’ lack of 70mm projectors, it’s been quite a challenge to get to a place where Tarantino and Nolan can make entire features using 65/70mm, but the preservation of film is turning in their favor.

Below, we’ve gathered 20 of the most essential 70mm film releases. From Stanley Kubrick to William Wyler and David Lean, it’s clear shooting in 70mm is mandatory for any epic filmmaker.

With additional editorial contributions from Zack Sharf.

“Oklahoma!” (1955)

Fred Zinnemann’s film adaptation of the 1943 stage musical was the first movie photographed using the Todd-AO 70mm widescreen process, resulting in an image that brought the depth and scope of the theater stage right onto the movie screen. The Todd-AO process allowed “Oklahoma!” to be shot at 30 frames per second, up from the standard 24, which yielded a crisper, more vibrant image. In its original theatrical release, the movie was distributed as both a cinematic roadshow (for the 70mm version) and a general release (for 35mm). In order to release the film in 35mm, every scene had to be shot twice on both formats.

“Ben-Hur” (1959)

“Ben-Hur” remains one of the biggest productions in film history: 200 artists were tasked with costumes, statues, and props; 200 camels, 2,500 horses, and 10,000 extras were used on set during production. MGM demanded Wyler and cinematographer Robert L. Surtees shoot in widescreen. The director initially opposed it because he didn’t want too much of the screen to go unused, so the studio created the MGM Camera 65, which used a special 65mm film stock with an extremely large 2.76:1 aspect ratio. The format proved essential for the movie’s centerpiece: A nine-minute chariot race in which widescreen photography captures the racers in the frame all at once.

“Sleeping Beauty” (1959)

“Sleeping Beauty” is one of the hallmarks of Disney animation, but it also happens to be a history-maker in terms of production. The movie was the first animated film to be photographed using the Super Technirama 70 widescreen process. Technirama traditionally used 35mm film, but the Super 70 process allowed the film to be made on 70mm stock. The result was a bigger and more visually immersive film than Walt Disney had ever released before.

“West Side Story” (1961)

Often considered the greatest movie musical ever made, “West Side Story” was shot using Super Panavision 70 by cinematographer Daniel L. Fapp. In order to capture the vibrancy and clarity of all those large and crowded dance numbers, Fapp and directors Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins knew the Super Panavision widescreen would be essential. It was one of the movie’s best production choices and turned set pieces for songs like “America” and “Jet Song” into iconic cinema.

“Lawrence of Arabia” (1962)

David Lean’s historical epic is one of the most stunning feature films in history because of F.A. Young’s Super Panavision 70 cinematography. Lean and Young were able to capture the massive expanse of the desert by using spherical lenses instead of anamorphic ones. Chronicling T.E. Lawrence’s WWI experiences in the Arab Peninsula, “Lawrence” was presented in two parts separated by an intermission, with the first half largely devoted to Lawrence’s emotional struggles and the second depicting the various battles he undertook as the leader of a guerrilla rebellion.

“It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” (1963)

Stanley Kramer’s comedy is a madcap adventure about a group of strangers who come together in order to locate $350,000 worth of stolen cash. The film was advertised as the first movie to be produced using one-projector Cinerama. Movies of this size traditionally used a three-projector system when exhibited, meaning three separate projectors would be electronically synced up and played onto one curved screen. The one-projector Cinerama allowed Kramer and cinematographer Ernest Laszlo to film in Ultra Panavision. The result was one of the biggest widescreen formats you could possibly get at the time. “Mad World” had a 2.75:1 aspect ratio.

“Cleopatra” (1963)

Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s historical epic starring Elizabeth Taylor is one of Hollywood’s most infamous productions. Budget overruns, casting changes, and production troubles nearly bankrupted 20th Century Fox, and a majority of scenes had to be entirely reconstructed and shot more than once. Mankiewicz and cinematographer Leon Shamroy originally began production using anamorphic CinemaScope but switched to 3-panel Cinerama during filming. Because of the budget overruns, all of the footage captured in these formats had to be thrown out, and the movie started production anew using the Todd-AO.

“Cheyenne Autumn” (1964)

“Cheyenne Autumn” doesn’t exactly rank among the best of John Ford’s films. One of his last works, the epic about a Native American tribe’s journey to their homeland from enforced exile is disjointed, overly long, and features slack directing from the filmmaking legend. However, it’s still well worth viewing for a few reasons. One is the experience of seeing Ford, whose classics are riddled with stereotypes of native people, implicitly wrestling with his negative portrayals through an act of cinematic apologia. The other is to see Ford’s first foray with 70mm film; shot by cinematographer William Clothier in Super Panavision 70, “Cheyanne Autumn” features some of the majestic and breathtaking landscapes of the director’s career.

“The Sound of Music” (1965)

The hills were alive and massive when “The Sound of Music” opened in a select 70mm roadshow format in 1965. The seminal adaptation of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, “The Sound of Music” was photographed in 70 mm Todd-AO by cinematographer Ted McCord. Director Robert Wise wanted to expand the scope of the musical and bring a cinematic quality to the story, hence all those sweeping shots atop lush mountaintops and in picturesque meadows. The Todd-AO film resulted in a smaller aspect ratio than Super Panavision, but it did support six sound channels, making it the ideal choice to shoot a big musical adaptation on.

“Playtime” (1967)

Director Jacques Tati’s magnum opus, “Playtime” features jaw-dropping cinematography from Jean Badal and Andréas Winding, who shot the absurdist comedy with 65mm Mitchell cameras. It’s necessary for capturing everything happening in the frame: For the satire of modern life, Tati commissioned a massive set to represent the city his protagonist journeys through and filmed on it for two years in a production plagued with difficulties. The result is a masterpiece, and one of the rare comedies that feels as epic as its 70mm format suggests.

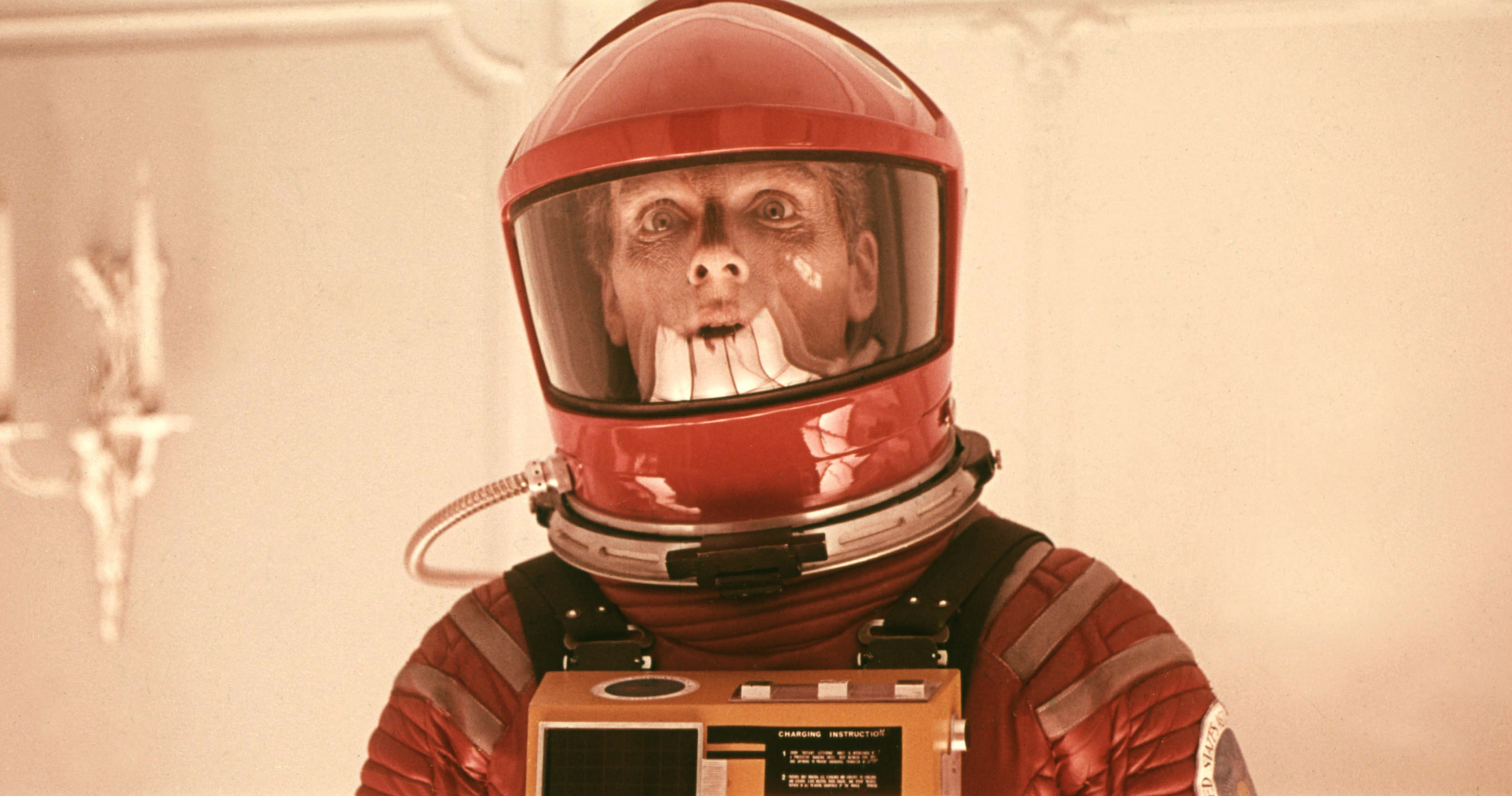

“2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968)

Stanley Kubrick’s magnum opus is largely credited as one of the most essential moviegoing experiences. Cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth took a page from “Lawrence of Arabia” and used spherical lenses and Super Panavision 70 film. The movie, which was presented in a Cinerama roadshow format, was projected in 2.21:1 aspect ratio on a curved screen with a six-track stereo magnetic soundtrack. No wonder the experience is so iconic. “2001” continues to tour the country on 70mm.

“Patton” (1970)

Franklin J. Schaffner’s biographical war epic “Patton” begins with an all-time great shot: General George S. Patton walking on stage with a massive American flag behind him. It’s shots like these that demand the scope of 70mm. “Patton” is one of only two films shot in 65mm Dimension 150, which was a variation of the Todd-AO 70 process that allowed the film to be projected on a deeply curved screen (the other film was John Huston’s “The Bible: In the Beginning”). Imagine how massive that American flag or those open field battle sequences probably looked in this format.

“Tron” (1982)

70mm was practically extinct by the time director Steven Lisberger and DP Bruce Logan decided to shoot “Tron” on Super Panavision 70 using a combination of various 65mm stock. Prior to 1982, the last 70mm release was James Clavell’s “The Last Valley” in 1971, and “Tron” would be the only 70mm movie for another decade. All of the live-action scenes in “Tron” were filmed in 65mm color, while the groundbreaking visual effects required black and white 65mm or traditional 35mm. The VFX portions of the film were then composited to VistaVision intermediate and printed on 70mm. It was a tedious process that drove up the movie’s budget.

“Akira” (1988)

A pioneering work of anime filmmaking, Katsuhiro Otomo’s “Akira” introduced Western audiences to Japanese culture and paved the way for adult animation to be taken more seriously as an artform. The introduction was appropriately epic thanks to the film’s format: Animated in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio and photographed on 65mm film, the cyberpunk action film gorgeously captures the ruined Neo-Tokyo of the original manga.

“Baraka” (1992)

“Baraka” is the first documentary ever filmed entirely in 70mm. Ron Fricke served as cinematographer on the non-narrative documentary “Koyaanisqatsi,” which was shot on 35mm, and aspired to create a similar study of human activities and technological evolution. Fricke shot “Baraka” in 24 countries over a 14-month period. He directed a sequel in 2011, entitled “Samsara,” which also used 70mm photography.

“Hamlet” (1996)

William Shakespeare’s most celebrated play has had dozens of film versions, but it wasn’t until Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 adaptation that the entire text of the tragedy was presented in its four-hour glory. So it’s fitting that Branagh shot the film in sumptuous 70mm, making for one of the last films to be screened in the format before its recent modern revival. Cinematographer Alex Thompson ably uses the format to capture the exquisite splendor of production designer Tim Harvey’s massive castle sets.

“The Master” (2012)

Panavision introduced an updated line of 65mm cameras in 1991 known as the Panavision System 65, but the box office failure of the first movie to use the technology, Ron Howard’s “Far and Away,” kept most studios away from using the expensive process. “Far and Away” and “Hamlet” were the only two features in the 1990s to be shot on 65mm and projected on 70mm, and the next feature wouldn’t arrive until Paul Thomas Anderson’s “The Master” 16 years later. The filmmaker used Panavision System 65 for nearly 85 percent of the feature and filmed the rest in 35mm. The 65mm footage was cropped from a 2.20:1 aspect ratio to a 1.85:1 in order to match the 35mm footage and keep the look of the film consistent.

“The Hateful Eight” (2015)

Quentin Tarantino and The Weinstein Company brought the glory days of Ultra Panvision 70 back to life with the release of “The Hateful Eight.” The director and longtime DP Robert Richardson decided to use Panavision anamorphic lenses so the film could have an aspect ratio of 2.76:1. The Western received the largest 70mm release since Ron Howard’s “Far and Away” over 20 years earlier. The costly exhibition process didn’t pay off as strongly as the Weinstein Company hoped, but that fortunately didn’t stop Warner Bros. from letting Nolan shoot “Dunkirk” entirely in 65/70mm.

“Dunkirk” (2017)

Ever since “The Prestige” in 2006, Christopher Nolan has utilized 65/70mm photography for different sections of his blockbusters. The iconic street chase between The Joker and Batman in “The Dark Knight,” the aerial prologue of “The Dark Knight Rises,” and the city folding in on itself in “Inception” were all made to feel bigger through the use of the Panavision System 65. But “Dunkirk” marks the first time the director has made an entire feature this way. Between the commitment to 70mm projection and the use of an IMAX camera for 75 percent of the movie, “Dunkirk” really is Nolan’s grandest-looking film to date.

“Oppenheimer” (2023)

The most recent major release to be screened in a 65mm format, Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is also the director’s best, a searing biography of the creator of the atomic bomb that’s both intimate and massive. Somehow, despite around 80 percent of the runtime consisting of discussions in meeting rooms, it feels well-suited for the format. Cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema used a combination of IMAX 65mm and 65mm large-format film while making the movie and even shot several scenes in IMAX black-and-white photography, a first. The result is gorgeous, especially in the centerpiece atomic bomb test scene.