Even at the height of its power, which was built (in part) on a series of sexual how-to guides and the second-hand credibility of an HBO documentary series, Vice wasn’t big on teaching people anything they didn’t already know. No, Vice was all about access. It was all about telling stories from the inside out, irrespective of journalistic ethics or integrity, in order to seduce the internet generation with the truth of a world too fluid and fucked up for the New York Times to understand.

That truth was typically facile and/or exaggerated (the average “Vice News” segment boiled down to some version of “we sent a twerpy white kid to a war-torn foreign country where cannibalistic soldiers are paid in bath salts, and holy shit was it scary”), but the illusion of extreme reporting played to the strengths of a brand that had always profited from selling freaks to squares, and supercharging that brand with the strength of traditional media turned it into an empire once valued at six billion dollars. I mean, it’s not like CNN could have — or would have — tagged along for Dennis Rodman’s VIP trip to the heart of Pyongyang, and that footage resulted in some of the most riveting TV I’ve ever seen, even if the piece said more about Kim Jong Un’s love for basketball than it did about his apathy towards the millions of North Korean people starving to death just out of frame.

But while Vice became the biggest job provider in all of Williamsburg by filtering the world through a singularly modern lens, the company was simultaneously embodying a tale as old as time: That of the balancing act between coolness and profitability. It was a balancing act that few companies have ever been worse at maintaining. And “Fresh Off the Boat” creator Eddie Huang, a writer, director, and TV chef who hosted four seasons of his own Vice travel show, had a front-row seat to see the whole thing wobble off its axis. In a way, that makes him the perfect person to create the definitive documentary about the rise and fall of Vice, just as it makes his film — which is much less interested in hard-hitting detail than it is in keeping it real — the perfect encapsulation of the media empire that it watches crumble into dust.

“Vice Is Broke” is by no means a great movie, but Huang’s refusal to budge from the courage of his convictions makes this deeply personal documentary something even better than that: It’s the movie that Vice deserves. Huang, who bailed on the success of his hit ABC sitcom the moment he felt like the network had betrayed his vision, is the kind of hyper-based iconoclast who was valuable to Vice for his authenticity until the minute that authenticity was no longer valuable to the brand — at which point Huang’s allergy to bullshit made him a liability.

“I was part of a cultural movement at Vice that was sold out from under us,” Huang writes in the documentary’s press notes, “and I’m big mad.” How big? As he explains to his soft-canceled friend and fellow Vice survivor David Choe as they get their palms read, he forfeited the hundreds of thousands of dollars Vice owed him so that he could be released from the NDA that prevented him from making this film. Huang was just too pissedoff that a handful of greedy assholes soiled a beautiful thing at their own expense, and he can’t abide the fact that another generation might come along and fuck up in all the same ways. Never mind that “Vice Is Broke” was shot during the moment of financial desperation that followed the birth of Huang’s first child at the height of the Hollywood strikes (“go home to your family!,” Choe yells at him), this dude has to say his peace.

And for better or worse, there isn’t a minute of “Vice Is Broke” where that personal animus feels like a put-on. “I’m sure there’ll be an Alex Gibney-esque documentary full of people sitting on stools that cuts this story into bite-sized pieces for mouth-breathers like it was about WeWork or Enron,” Huang says at the start of the movie, “but Vice was different because at one point it meant something to people.” He was one of those people, he swears to God it didn’t have to end like this, and we believe him on both counts.

Huang is a self-avowed student of Anthony Bourdain (to whom this film is dedicated), and he embodies a similar man of the people straight talk. Not everything he says is the stuff of poetry, and his need to perpetuate street truth sometimes leads him around to some back-alley bullshit (likening Nobu to The Cheesecake Factory is almost as hard to swallow as the fact that he sees The Fat Jewish as a source of radical honesty), but the film is full of evidence — new and archival — that convincingly illustrates Huang’s willingness to speak his mind at his own expense.

The same is true for many of the ex-Vice staffers who Huang interviews here, most of whom are positioned on couches or lawn chairs in order to disguise how this is basically a documentary full of people sitting on stools. Like Huang, these people were misfits who felt like they had a home at Vice, and the director is sympathetic towards their reluctance to throw that away for a few red flags.

One writer remembers telling neo-edgelord turned Proud Boys godhead Gavin McInnes that she was inspired by Vice magazine’s female sex columnist, only for the Vice co-founder to reveal that he was Vice magazine’s female sex columnist. Her response: “Okay, well I want to write like that anyway.” And when McInnes started making Hitler jokes around an Orthodox Jewish employee who never fit in with her family? Well: “Sometimes you love people that hurt you simply because they were the first to love you at all.” So it goes with a company started by three guys who stole it away from a non-profit magazine written for Haitian immigrants in Montreal.

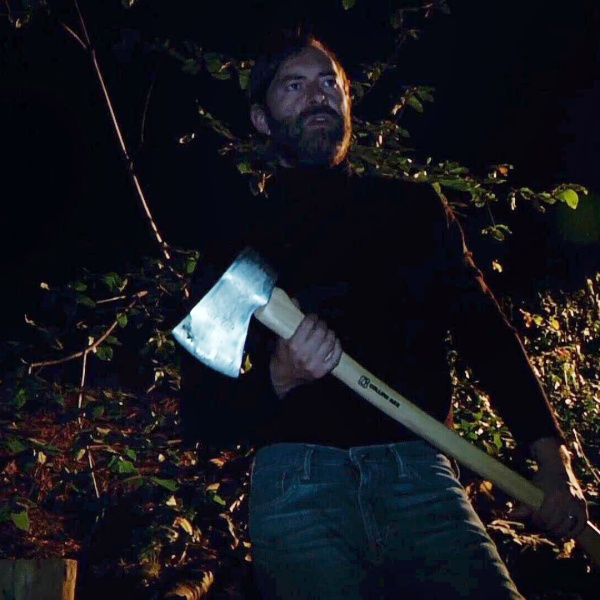

Interestingly, Huang sees McInnes’ heel turn toward nazism as an early symptom of Vice’s inauthenticity, and in an interview that turns out to be more trouble than it’s worth (and ends with an arm wrestling match), Huang essentially accuses McInnes of faking it for clicks. “I think Gavin is less of a white supremacist than a nihilist who loves making people uncomfortable because that makes him feel powerful,” Huang says, before likening the schtick to Kevin Spacey’s character in “The Life of David Gale” (complete with a clip for illustrative purposes), which has to be one of the funniest and most sincere pulls I’ve ever seen in a documentary.

I tend to think it doesn’t really matter whether someone is doing neo-fascism as a goof, but Huang simply can’t stomach any bullshit, which makes McInnes’ fellow co-founder Shane Smith — who would become the face of Vice during the company’s heyday, and the chief architect of its implosion — the real target of his ire. A self-mythologizing profiteer who was good at gloating about the success of a brand he was never charismatic enough to embody, Smith is framed in a way that screams “hipster Zaslav” even before the current Warner Bros. CEO shows up to complete the illusion.

Smith rejected a $3 billion offer from Disney (of all companies) in order to let Vice grow organically, only to turn the brand into a house of cards held up by fake traffic numbers, backwards-facing business models, and an insatiable lust for profit. Vice sold cool, but every white-label spon-con deal it brokered with Philip Morris lessened its currency among the very people who believed in it.

Huang will never forgive Smith for killing the golden goose, and Smith will probably never take responsibility for it (to judge by the Instagram message with him that Huang shares in the film), but that’s not really what this raw and well-relished documentary is all about. While “Vice Is Broke” points a lot of fingers, even casual bystanders could identify the culprits a mile away.

Huang is more interested in underscoring the importance of staying true to yourself at all costs (a point he satirizes by doing an entire interview as the Asian Guy Fieri clone his Smith-installed producer wanted him to be). He’s not getting that money back, so he might as well help people to see Vice for the cautionary tale that it is — one that will only become more relevant as vertical integration and the push for constant growth eat up what’s left of American journalism like an easily preventable cancer. His generation might be cooked, but it might not be too late for the next one to write a story that hasn’t already been told to death.

Grade: B

“Vice Is Broke” premiered at the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best reviews, streaming picks, and offers some new musings, all only available to subscribers.