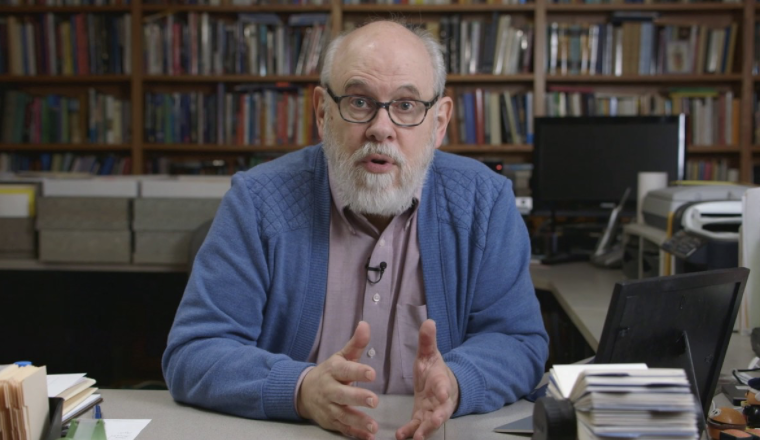

He simply may have watched more movies than anyone else alive. That’s the kind of legendary detail that followed film scholar David Bordwell, dead at 76 after a long struggle with a degenerative lung disease.

Was that true? Impossible to determine, and Bordwell’s cinephilia was never about bragging or the accumulation of knowledge to score points — but instead, to share with others and enrich our collective understanding of cinema. If you studied film on any level in academia, you almost certainly have heard his name.

For several generations of film students, you read Bordwell’s “Film Art: An Introduction” in your fall freshman Film 101 class. That was me in 2004, and I believe that book was already on its seventh edition by that point — it had first been published in 1979. If you went deeper into your studies, you’d undoubtedly encounter his “Film History” textbook as well. Both of these he co-authored with his wife and fellow University of Wisconsin-Madison film professor Kristin Thompson.

Together, Bordwell and Thompson kept film studies graduates enthralled well after the conclusion of their studies by publishing an authoritative blog at davidbordwell.net and contributing a series of video essays to the Criterion Channel titled “Observations on Film Art.” The series ran 50 episodes, beginning with “Musical Motifs in ‘Foreign Correspondent,’” a tribute to Alfred Newman’s bouncy score for the Hitchcock film, and ending with “Rock and Roll Style: Props and Costumes in ‘Quadrophenia.’”

Bordwell and Thompson’s blog remains a definitive treasure trove for cinephiles online, with article categories broken down by director, national cinema, below-the-line craft, and more. It reflects a special romance — may all of us find a life partner so completely on our own wavelength — and shows their uniquely welcoming spirit. Every genre is covered here, every type of film worthy of some aesthetic consideration.

Bordwell considered “The Hunt for Red October” to be among his favorite films of all time and devoted several blog posts to it. Also on his list of favorites? “How Green Was My Valley,” “Choose Me,” “Back to the Future,” “Song of the South,” “Passing Fancy,” “Advise and Consent,” “Zorns Lemma,” and “Sanshiro Sugata.” That’s a little bit of everything. No snobs when it came to blockbusters, Thompson herself wrote a book on “The Lord of the Rings” called “The Frodo Franchise.”

Bordwell proved that the best way to be a cinephile is to be open to everything. Of course, that doesn’t mean you like everything. It’s been almost 16 years, and I remember vividly his frustration with “The Dark Knight,” calling it “portentously hollow.” Among other things, he and Thompson have been the premier chroniclers of the way Hollywood tells stories (their 2006 book on this is literally called “The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies”), and how certain storytelling virtues have atrophied while still popping up in unexpected places. He could single out David Koepp’s “Premium Rush” for praise in a way that he wouldn’t “The Dark Knight.”

Bordwell and Thompson have never exactly been critics, in the weekly reviewing sense. They were more interested in the “how it works,” “why this matters,” and “why we respond the way we do” of film — their analyses all about taking the filmic toys apart just to have the fun of putting them back together again. It’s what made so many of Bordwell’s non-textbook books so enriching: “Planet Hong Kong” about the Hong Kong film industry, “Poetics of Cinema,” rooted in a deep appreciation of Ozu, and “The Rhapsodes,” about how 1940s film critics shaped the idea of film criticism we have today. These are books you can keep coming back to decades after leaving your university campus behind.

For those in academia today, you’d do well to model yourself after Bordwell and Thompson: They proved that deep understanding should be connected to accessibility, and that good writing is more important than academic jargon.

For critics, you’d do well to model yourself after Bordwell and Thompson, too: Root your work in the deepest possible knowledge of your subject — if that’s film: how it works, what techniques it uses to make you feel the way it does, where the art of it intersects with the business of it.

Bordwell is gone. But he still has so much to teach us.