There are several moments in “Uprising” — a spirited but overstretched Korean epic set during the years following the 1589 rebellion of Jeong Yeo-rip — where it feels gleefully obvious that the film was written by Park Chan-wook, whose mordant sense of humor and operatic approach to violence stick out from this story like an artfully framed sword lodged into a dead soldier’s neck. (Lest that example fail to convey Park’s signature touch, I should note that the actual sword in question is held by a hand that’s been sliced off at the wrist.)

Alas, those moments are severely outnumbered by the ones in which it’s just as obvious that the film was directed by someone else.

While former art director and frequent Park collaborator Kim Sang-man brings a rousing bloodlust to this fast-paced saga of revolt and betrayal, the unwieldy war story he’s forced to wrestle into submission can’t help but feel a bit shapeless without the precise sculpting of Park’s camera. “Uprising” is too watchable and well-staged to suggest that Kim was set up to fail, but the movie — overwhelmed by the sheer amount of ground that it has to cover — retreats towards a conventionality that dilutes its emotional strength and belies the singular flair of its best scenes.

Backdropped by a chapter of Korean history so complicated and unsettled that scholars are still at odds over the truth of what happened, “Uprising” streamlines one of the bloodiest purges of the Joseon Dynasty into an all-too-familiar tale of childhood friends who are torn apart by the same political circumstance that will ultimately force them back together in a fight to the death.

Jong-ryeo (Park Jeong-min) is the high-born son of Joseon’s chief military official, the most trusted advisor of the sociopathic King Seonjo (Cha Seung-won, delightful in a performance that drips with Park Chan-wook’s droll mirth). Cheon Yeong (“Broker” actor Gang Dong-won) is the penniless slave who’s assigned to receive Jong-ryeo’s beatings whenever the master’s kid messes up — a nobleman can’t afford to be covered in scars. The two boys form a bond that continues into adulthood, when the preternaturally skilled Cheong Yeong is promised his freedom if he passes a military exam on Jong-ryeo’s behalf.

A less naive person might have recognized the falseness of that promise, but Cheong Yeong fails to appreciate how the king’s ruthless control depends upon a lack of social mobility; so far as King Seonjo and his feckless minions are concerned, slavehood isn’t a social condition so much as a permanent scar. Such thinking stems from the rebellion that “Uprising” races through in its opening text, which recounts how the scholar Jeong Yeo-rip was accused of high treason for insisting that all men are born equal (his punishment was, you guessed it, a sword through the neck).

Jong-ryeo has no choice but to allow his best friend to be executed, but the invading Japanese burn down the King’s palace before the sentence can be carried out, and Jong-ryeo’s wife and son die in the fire. Cheong Yeong uses the smokescreen to slip away and join the resistance movement, leaving Jong-ryeo with the mistaken belief that the ex-slave was responsible for the deaths of his family.

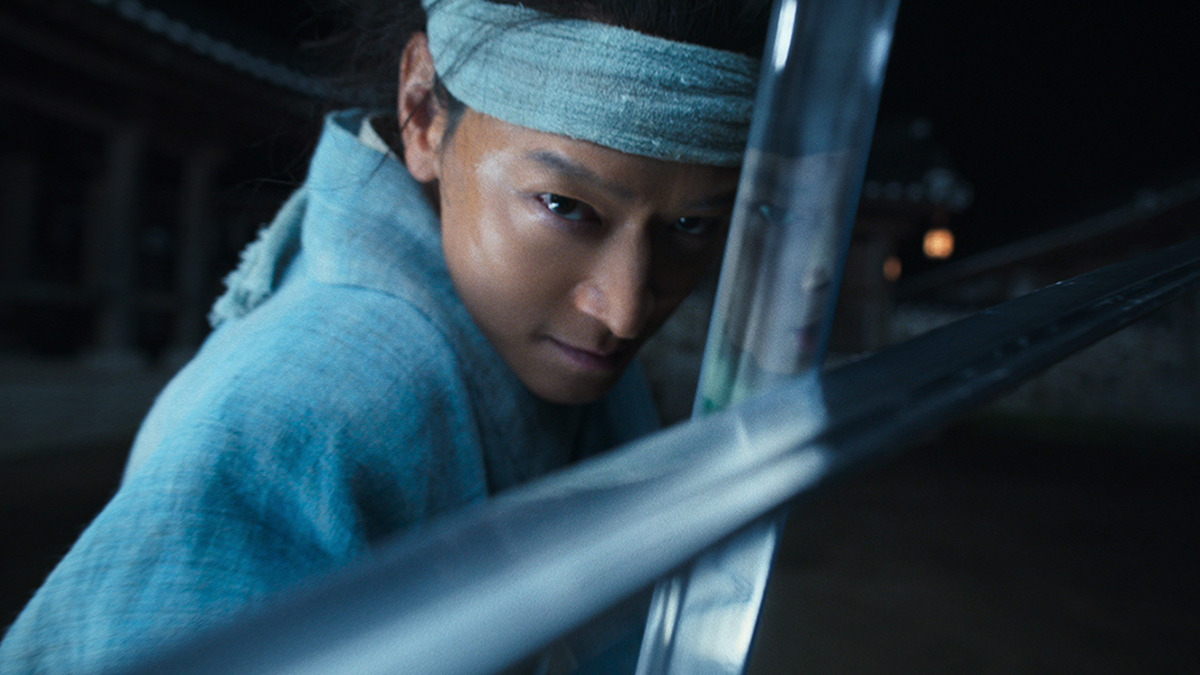

That tragic misapprehension has already mutated into a frenzied mania when the action picks up again seven years later, by which point Jong-ryeo has become the mad king’s favorite warlord and Cheong Yeong has established himself as the “Blue-Robed God” of the Righteous Army that’s rising up against the crown. There are shades of William Wallace to the latter’s evolution from common man to folk legend, but Park’s script can’t stomach the sort of unalloyed martyrdom that made “Braveheart” feel like a practice round for “The Passion of the Christ,” and his Cheong Yeong is mercifully denied any self-righteous speechifying. He doesn’t even get a dead wife or a chance to moon the vanguard of Japanese soldiers who complete the movie’s scalene triangle of armed conflicts; they’re represented by the cruel frontline commander Kikkawa Genshin (Jung Sung-il), who’s known as “The Nose-Snatcher” on account of the fact that he likes to cut off his enemy’s noses after he kills them. Park and/or Kim are predictably obsessed with that detail, and it’s safe to say that “Uprising” features more severed noses than any other movie ever made.

At the same time, the film’s measured refusal to make its hero seem larger than life would be more refreshing if it found anything of substance to replace that with; it doesn’t, and Cheong Yeong spends most of the movie staring into the wind with a stoic look on his face or stewing on his failure to appreciate the king’s duplicity. Gang gives some really strong face, but it’s a good thing that Cheong Yeong is able to express himself so clearly with a sword, as the character may not have registered at all if not for the figure he cuts during the story’s florid and frequent action scenes.

Well-staged without being overly balletic, the combat has a way of revealing the pulpy B-movie that “Uprising” wants to be at heart, as crunchy guitars and grindhouse zooms suggest that the more pressing war at hand in this epic is the one between the gravitas of its historical story and the levity of its telling. The humor tends to exert a much stronger pull than the drama; the mutual grievance between Cheon Yeong and Jong-ryeo never creates the kind of emotional undertow needed to keep the movie on track through years and years of civil strife, but I laughed out loud at the scene where Kim Shin-rok’s Beom-dong mocks Cheon Yeong for dragging out the most important swordfight of his life (Kim is a major standout as an uncompromising militia leader whose cynicism is rewarded at every turn).

Pointing fingers isn’t all that fair or helpful, as it’s possible that Park is at fault for how frequently “Uprising” gets sidetracked by the king’s obsession with rebuilding his palace, and all the more so for how the film entrusts its most essential character dynamics to flashbacks that arrive way too late to matter. But history suggests that the “Decision to Leave” director is uniquely skilled at threading the needle between intimate human desires and the larger tapestries of violence into which they’re sewn, and “Uprising” too often feels as if its personal drama is completely separate from the sociopolitical circumstances that define it (a feeling reinforced when the film ends with one of those things resolved, and the other very much still in flux).

There’s good fun to be had in watching so many limbs get hacked off for the better part of two hours, but Director Kim can only dismember so many body parts before he starts to lose track of his movie’s spine.

Grade: B-

“Uprising” will be available to stream on Netflix starting Friday, October 11.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best reviews, streaming picks, and offers some new musings, all only available to subscribers.