For those without a clear understanding of the type of architecture explored in Brady Corbet’s Silver Lion-winning “The Brutalist,” a main feature of brutalism is a balance of maximalist and minimalist features. While many brutalist buildings carry an expressionistic beauty, they are often constructed using exposed, raw materials like concrete and brick, hence the barbarous nomenclature. In assembling this film, co-screenwriter Mona Fastvold, composer Daniel Blumberg, DP Lol Crawley, and production designer Judy Becker all believed that juxtaposing these two opposing ideas held within brutalism was key to communicating the story put forth in “The Brutalist.”

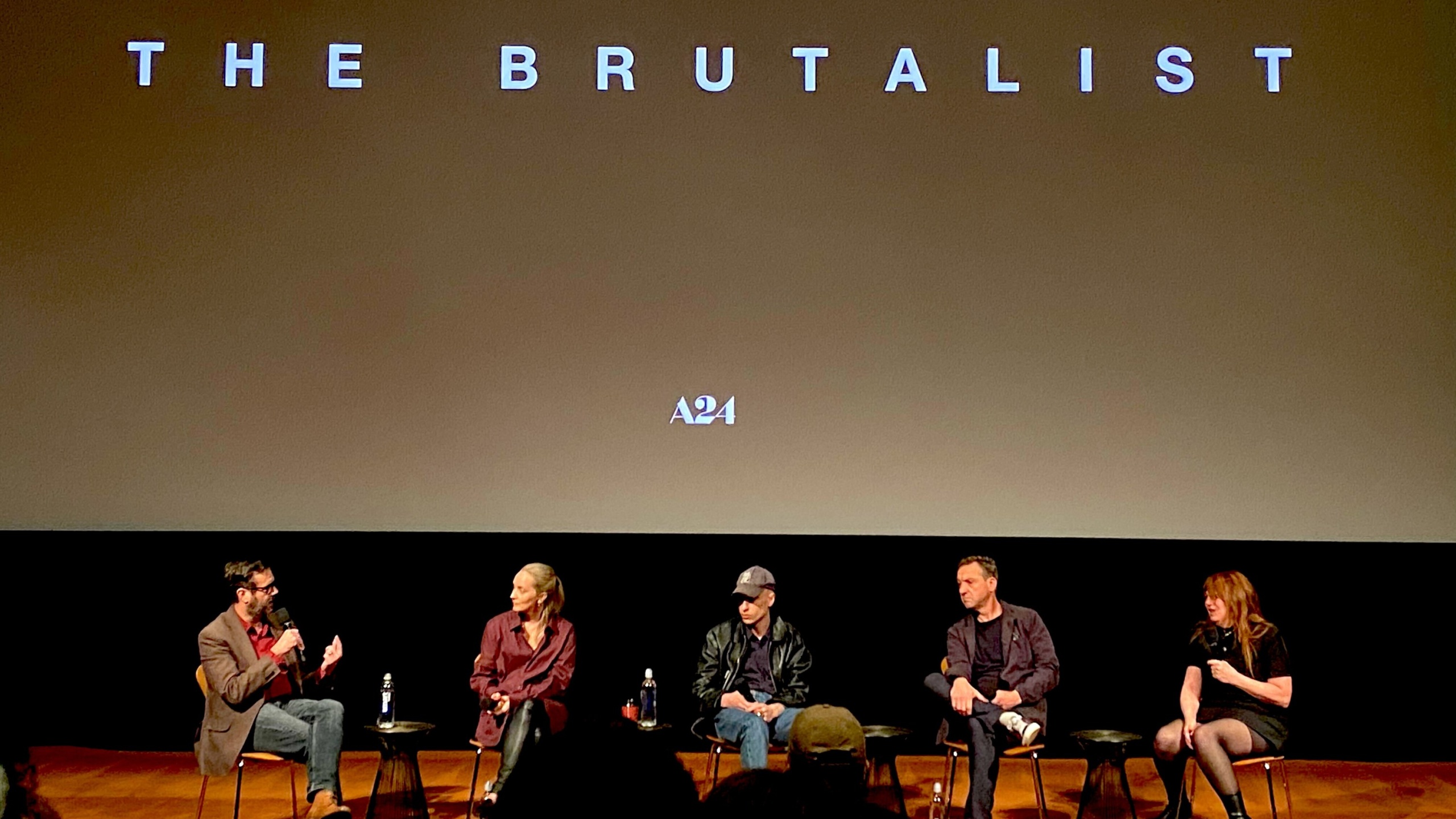

Speaking with IndieWire’s Jim Hemphill following a screening on Sunday at the Linwood Dunn Theater in Los Angeles, the team went into detail about how they approached their specific responsibilities to the project with a unified vision. For Blumberg’s part in composing the score, his biggest challenge was finding the right instruments to match the time periods the film travels through. He told the crowd that he came upon the piano “quite early” considering it could be used to reflect the more melodic tones of architect and Holocaust survivor László Tóth’s journey, as well as the intense noise that comes with being thrown into the American machine.

“The idea that it could kind of both be this intimate thing and then this quite like big percussive — some of the low end is from putting lots of microphones on the base of the piano,” Blumberg said. “And with the brass as well, it’s the same, it can be something that’s very kind of soft and warm and then also very harsh. And a lot of the brass players, they are quite unique players like Axel Donner, who played the trumpet. It’s making very peculiar sounds related to the construction.”

Capturing this dichotomy was also integral to Crawley’s process as well, which is why he chose to shoot a lot of the film handheld, while at the same time making space to use VistaVision for some of the more epic sequences, like when Tóth (Adrien Brody) and benefactor Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce) visit the Carrera quarries in Italy to select marble for their “shared” creation. This contrast within the imagery, Crawley believes, echoes Tóth’s own experience and inner conflicts.

“He has this kind of absolute, far-reaching, epic, ambitious desire,” said Crawley, “but also is balancing that with the intimate, with the family, with the idea of the sacrifices one makes, consciously or unconsciously — the personal sacrifices or emotional detritus that comes from seeking to pursue this artistic vision.”

At the root of Tóth’s artistic vision is a desire to reclaim the spaces that brought such harm and upheaval to his life: The concentration camps he, his wife Erzsébet (Felicity Jones), and his niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy) were all forced to inhabit during Nazi rule in Europe. In honoring Tóth’s experience and how that influenced his architecture in the film, Becker felt it was important for her to fully take hold of what he must have gone through and to build as he would have built coming out of it.

“The most difficult thing for me was how to incorporate the architecture of a concentration camp into a building in a way that made sense,” Becker told Hemphill. “And so the most research I had to do was really on that and on looking at a lot of imagery from concentration camps, which was emotionally pretty draining and difficult, because I really had to think about it and think about it objectively as a designer and emotionally because that’s something that László had been through and was coming from.”

None of the work of these craftspeople would’ve been possible, however, without a strong foundation provided by Corbet and Fastvold’s expansive script. Both had grown up around architects and were also used to tackling period pieces that place fictionalized characters against society-shifting historical events, so the element that took the longest time was sifting through research.

They were particularly taken with the work of German-Hungarian architect Marcel Breuer, though he emigrated to America as Jewish persecution in Germany was ramping up in the 1930s. Once they felt enough information was in their brains however, Corbet and Fastvold worked to transmute it all through their own experiences, ending up with the story of a trauma-ridden creative who’s willing to face continued moral and physical degradation for the chance of bringing his vision to life.

“This film was shot in 33 days and it was made for $10 million. The films that we have made throughout our career are always on a tight budget and they’re difficult to make and this film was very difficult to get off the ground,” Fastvold said. “Of course, part of that was COVID, which, we can’t complain about because people suffered so much during that, but still, it took such a long time to get this one on its feet.”

She added later, “There’s a lot of similarities between erecting a building and making a film. You hire hundreds of people. We all have to function together. You have a crazy, wild dream that you invite everyone in to come and try and realize with you. It’s madness.”

A24 releases “The Brutalist” in theaters on December 20.