The following op-ed was provided to IndieWire courtesy of the team behind “Sing Sing.” It’s written by Sean Boyce Johnson, a Yale-educated actor, about his father Sean “Dino” Johnson, who stars in the A24 film but is also an alum of the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program. He was incarcerated during much of his son’s childhood, as Sean Boyce Johnson explains below in his tribute to his father.

Starring Colman Domingo and written/directed by Greg Kwedar with co-writer Clint Bentley, “Sing Sing” incorporates many alumni of RTA in the film‘s ensemble in its story of a small theater group formed within the titular New York State correctional facility. The program operates in 10 maximum and medium-security men’s and women’s New York State correctional facilitiesand aims to reduce recidivism rates by providing people who are incarcerated with critical life skills through the arts.

My father and I both became actors, but through very different paths. I developed my skills at Yale School of Drama while my dad honed his talents through the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program while incarcerated at Sing Sing Correctional Facility. Today, we are both working actors and advocates of the power of the arts — a craft that has brought me closer to my father, Sean “Dino” Johnson.

My relentless imagination made me unpunishable as a child. I grew up in New York City as an only child in a single-parent household. With my father, Sean “Dino” Johnson, incarcerated for most of my developmental years, I had little choice but to daydream and create my own worlds. When toys and video games were taken away because of a bad grade, I would escape to my room, crafting elaborate tales and performing for my captive audience: my mother, visiting relatives, and friends. My persistent imagination became a lifeline, a thread that connects me to the past and is a guide for my future.

My late mother, Wendy R. Boyce, was a cinephile who instilled in me a love for film, especially the classics of “Old Hollywood.” I was practically raised on independent films, DVD commentaries, and the Turner Classic Movies channel. Films like “Madame X,” “Leave Her to Heaven,” “Imitation of Life”, “Calamity Jane,” and “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” were all early favorites. Later in life, I inquired about her only tattoo: a pair of comedy/tragedy masks. She revealed that she secretly dreamed of being an actress but never pursued it due to severe stage fright. To be clear, she wasn’t a stage mom by any means. In fact, she encouraged my pursuit of other avenues, but her vivid imagination and love for storytelling were contagious, shaping my path in ways I didn’t fully understand until much later.

While serving time in Sing Sing, my father honed his craft with the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA), a program that he helped found and recruit for. His work with RTA profoundly enriched his personal and professional life. Through acting, he evolved into an empathetic man and an effective communicator. He learned to express his anger and to communicate love without shame. Unbeknownst to me, my father was using storytelling to reclaim his dignity and humanity in a place designed to strip it away.

I grew up harboring resentment for my father’s absence. But when I first saw footage of him performing, I felt an instant connection — a realization that we shared an unbreakable bond through our love for acting. I was finally able to see the RTA performance tapes with my father after he came home, when I was about 15.

Today, as a working actor and screenwriter, I see how deeply this desire for expression is rooted in my family. The fact that we pursued this craft independently speaks to a profound inheritance of creativity, perhaps shaped by genetics and a greater divine order. As an artist, you often feel like a black sheep, and the desire to act seems elusive and misunderstood. Seeing my dad perform for the first time made it real; it affirmed my passion and my connection to him. I felt seen in my journey, and I understood then that this wasn’t just a dream but it was a calling.

The arts have made us both unpunishable — by our circumstances, by our pasts, and by the challenges life throws our way. This creative path has transformed my relationship with my father, finally allowing me to say “Dad” with assuredness and love, a word that once felt strange on my tongue.

My journey in acting, from performing in the UK as a teen, studying at the Yale School of Drama, to building a career, has not only been a personal triumph, but it is also a testament to the legacy of my parents. Whether they knew it or not, they have served as architects to my passion, guiding me through the labyrinth of a life dedicated to storytelling.

Some of my most cherished memories with my father after he was released are tied to our shared love for the craft. From him taking me to get my first headshots to chaperoning some of my early auditions, he has been a mentor and ally in a field we both love. Now, when we help each other self-tape or prepare for an audition, our bond deepens. For one of my first roles on television, I played a probation officer. I immediately called my dad, asking him about the probation experience. His guidance has helped me choose roles wisely, seeking ones that defy stereotypes, as we continue to find strength and joy in our mutual passion for storytelling.

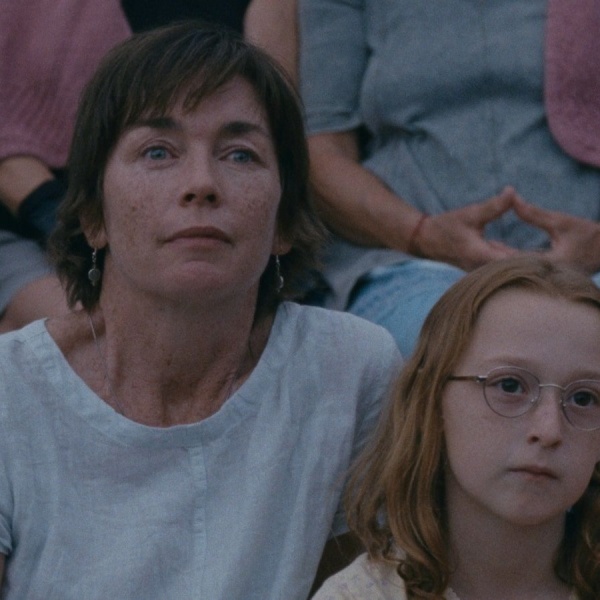

Watching my dad in the movie “Sing Sing” felt surreal. I was overcome with pride, not just as his son but as a fellow actor. I know that for any artist, the journey is long, but his has been something else entirely. It has been extraordinarily beautiful to witness his trajectory. Art truly saved his life.

In the film, he delivers a powerful line: “We’re here to become human again.” That line captures my father’s journey. It’s one thing to go to a training program and learn to expand one’s imagination; it’s another to do so in a place meant to tear at your humanity. In that program, expanding one’s imagination is a fight for your soul, a fight for joy.

I believe the craft of acting is a service job. “Sing Sing” is an artist’s film, one that reaffirms the possibility of reclaiming humanity. It shows the contagious power of resilience and compassion, inviting audiences to expand their empathy and imagination.

The last performance my mother was able to see me in was Shakespeare’s “Titus Andronicus” during my second year at Yale, where I played Aaron the Moor. Aaron is a well-known villain, and he’s written as such, but I didn’t play him that way; everyone has a reason or a story behind their actions, and in retelling his, I felt compelled to defend him, to creative a new why. I could create a new life for him.

In a world that seems to lack compassion and empathy, where many feel constrained by their circumstances, I urge us all to remember the power of human imagination. It can truly be a lifeline, a means of healing, and a bridge that connects us to one another. For my father and me, storytelling has not only become a sanctuary but a means to reclaim the time that was lost, forging an unpunishable bond through creativity, resilience, and love. And as we face an era of division, let this film serve as a reminder of what’s possible when we allow ourselves to become human again.

“Sing Sing” is now available to stream.