The story of the 6888th Battalion, AKA the “Six Triple Eight,” was unfortunately destined to be overlooked in the annals of World War II history. The predominantly Black unit of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) was responsible for overseeing the logistical nightmare of sorting and delivering 17 million pieces of backlogged mail. Though the mission might carry the patina of busy work, anyone with a working heart can understand how general morale might be improved by reliable communication between soldiers and the home front. The 855 members of the Six Triple Eight ultimately accomplished their daunting six-month task in just three months, much to the surprise and resentment of Army leaders who weren’t keen about Black leadership, or the specter of desegregation, in the armed forces.

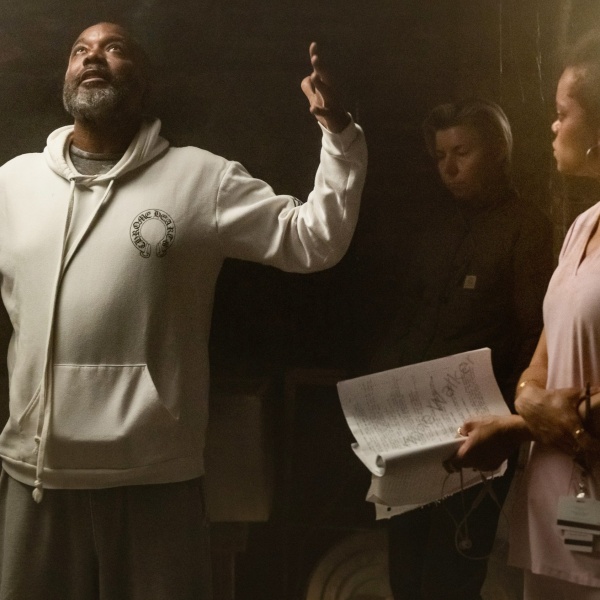

With “The Six Triple Eight,” writer/director Tyler Perry attempts to right the historical record by paying tribute to these historically neglected women. His third directorial effort this year, and his second for Netflix, chronicles the battalion’s story through the eyes of two real-life figures: Major Charity Adams (Kerry Washington), the leader of the 6888th who fights uphill against institutional bigotry when she’s not whipping her unit into shape, and Lena Derriecott (Ebony Obsidian), a young woman inspired to join the war effort after her childhood love Abram David (Gregg Sulkin) is killed flying planes over Italy. Their personal experiences in the WAC, from basic training in Georgia to their main postal assignment in Europe, broadly inspired the film’s events.

Perry uses his film to repeatedly underline that Lena, Major Adams, and the rest of the 6888th are heroines who should be widely recognized by the public. His insistence on this point amounts to the film’s motivating concern, and though he’s obviously correct that most Americans are likely unaware of this particular slice of history (even after receiving more public attention in recent years), this aspiration ultimately makes for shallow dramatic portraiture. The goal of extolling the Six Triple Eight’s virtues renders the film’s narrative an incidental element. By design, the characters are primarily symbols rather than full-fledged personalities, with performances tailored to either saintly or villainous ends.

Veneration doesn’t necessarily beget clichés, but Perry’s passion for the generic knows no bounds. Every battle scene, basic training montage, or sequence of R&R has a secondhand quality, as if they were hastily cobbled together from memories of other war films. The two-dimensional characters communicate in bromides; Lena’s fellow privates, who suffer from the laziest defining characteristics (coarse Southern gal, proper preacher’s daughter, New Yorker), are the worst offenders. The racist white leadership, embodied by Dean Norris’ sneering General Halt, can’t help but feel cartoonish, even as their behavior was undoubtedly historically accurate. It’s plainly upsetting to watch white men browbeat Black women, but it carries little dramatic weight because the cruelty is nonspecific. “The Six Triple Eight” exists to stir emotion by any means necessary and from any flimsy source it can find.

But stirring moments become forgettable treacle when piled on top of one another. A scene in which Major Adams proves to the Army leadership that her cold, tired unit could march in perfect unison immediately after disembarking an ocean liner forced to violently evade U-boat attacks exhibits emotional potency. But every prior or subsequent scene with Major Adams standing up to the brass acts like a tired retread of itself. A climactic moment features General Halt telling Major Adams that he should bring a white lieutenant to run her unit following a harsh inspection of the 6888th postal operation, to which Major Adams responds, “Over my dead body.” This incident actually occurred, but Perry never lends it the necessary gravity because “The Six Triple Eight” is replete with such scenes. (The less said about the following scene, in which the unit expresses gratitude for the Major’s rebuke in a possibly-unintentional homage to “Dead Poets Society,” the better.)

Even if Perry’s lionization effort generated a compelling film, his insistence upon an overwhelming saccharine tone undercuts the material at almost every turn. It’s downright strange how often the film lingers on close-ups of the tear-stained faces of the 6888th, especially considering that Perry emphasizes their strength and dignity. Worse still, Lena’s brief courtship with Abram, whose death Perry telegraphs in an insultingly heavy-handed way, makes so little impact because, again, the characters and their relationship never rise above the archetypal. Nevertheless, Lena’s grief over his death becomes her defining characteristic — she regularly sees visions of Abram, who tells her not to give up during basic training, and sobs at the slightest reminder of his memory.

The real Lena Derriecott was the subject of the film’s source material, a WWII History Magazine article by historian Kevin M. Hymel, which paints her as a civic-minded young woman active in her community before she joined the WAC. When she wasn’t on duty in Europe, she got to know the “war-weary citizens of Birmingham”; later, when the unit was transferred to France, she discovered her love of baguettes. She won multiple art prizes while stationed in Rouen and eventually studied design in England before returning to the States. Perry is under no obligation to incorporate these details into his film, which covers just a slice of the 6888th’s history anyway, but the fact that he characterizes Lena primarily via her relationship to Abram without even hinting at any interiority beyond him greatly disappoints.

“The Six Triple Eight” spends relatively little time on the unit’s actual mission, likely because of the concern that “sorting mail” lacks conventional excitement. It’s ironic that the scenes featuring the battalion strategizing how to break the mail logjam are the most fascinating. The women quickly discover that trying to organize the mail by unit number isn’t sufficient because of the frequency of transfers. On top of that, the commonality of names and general writing illegibility makes deciphering locations particularly difficult. Hence, they’re forced to improvise clever solutions to this problem.

An entire film that focuses on untangling this organizational mess clearly exists, but Perry would much rather lean on trite platitudes that state the obvious again and again, rather than trust the “boring” nuances of the historical record. From beginning to end, “The Six Triple Eight” never trusts its audience to actually engage with the material beyond its inspiring surface, evidenced by a lengthy coda featuring title cards that literally restate the film’s plot over archival footage of the 6888th Battalion. Unsung heroes deserve better.

Grade: C-

“The Six Triple Eight” is now streaming on Netflix.