“Nightbitch” spends way more time on the wildness of being a parent than the wildness of turning into a dog — however interlinked those two phenomena become for the film’s protagonist (Amy Adams). Writer and director Marielle Heller wanted to take the experiences that resonated with her from the Rachel Yoder novel of the same name and find viscerally cinematic ways to represent them.

But not so unlike motherhood itself, there’s a wealth of work that goes into the success of the simplest onscreen actions — from the punch of a hash brown hitting a frying pan to a toddler (played by twins Emmett Snowden and Arleigh Snowden) waving at a garbage truck right at the moment the camera needs them to. In fact, Heller found that a lot of fun and games were required to get her youngest actors to help the film’s project of centering the ways in which raising kids is never all fun and games.

“It was a huge goal of mine to be able to capture a relationship between a mother and a child that felt authentic. Because for me, when I watch most movies or TV that have little kids, it feels like total bullshit. You know, it’s this perfect little actor kid doing actor-y things that don’t feel like a real kid. Or it’s parents responding in ways that don’t feel real,” Heller told IndieWire on the Filmmaker Toolkit podcast.

To avoid that common pitfall, Heller’s nontraditional audition process for the film’s son involved a lot of just hanging out in the park and playing with kids. It also involved making sure they’d exude a sense of play and mischief but also follow directions when they needed to and not get too shy on a film set. It helped that almost every “Nightbitch” crew member was a parent or very familiar with little kids.

“Everybody collectively decided we were going to make this a really fun place for these kids,” Heller said. “[Emmett and Arleigh] knew everybody on set. If somebody’s coming up with a microphone, they knew his name, and what he was doing, and why he was there, and how the microphone worked. A huge amount of work [went into] creating an environment where they felt really safe.”

Heller herself put in a huge amount of work into getting her toddler actors to do exactly what each scene in the film required, from smashing a plate of spaghetti to toppling Amy Adams and covering her in paint. Heller calibrated simplified acting games for the kids but also used the kind of reverse psychology anybody can tempt a toddler with. “[I’d go] ‘Don’t bark, whatever you do, don’t bark right now’ or something and barking at them and seeing how they’d respond,” Heller said. “It was a little awkward when my two-year-old daughter visited [the set] and she saw these two little boys, like, in my lap. The look on her face was like, ‘What is happening here?’”

Familial betrayal, however benign, is germane to the story and the themes “Nightbitch” explores. Heller uses all the cinematic tools at her disposal to show the mother’s struggles simply managing chunks of time, day after repetitive day. There’s an intriguing discomfort to Nate Heller’s score and how Marielle uses sound, plus a kind of percussive editing rhythm to make the film’s mundane events feel heavy and its surreal events feel sublime.

In a childcare montage near the film’s beginning, for instance, Heller wanted to capture how jarring ordinary moments can be when you’re sleep-deprived and stuck with a toddler. And without making anything in the film ever feel like a jump scare. So she structured the actions and the shooting of that montage to turn normally pleasant sounds — food sizzling in a pan, swings squeaking in a park — into jarring, percussive elements.

“[Editor Anne McCabe] and I had so much fun and she found little things that I hadn’t even planned on — a moment where the son says, ‘Seven, eight,’ and it sounds like he’s counting off the percussive elements,” Heller said.

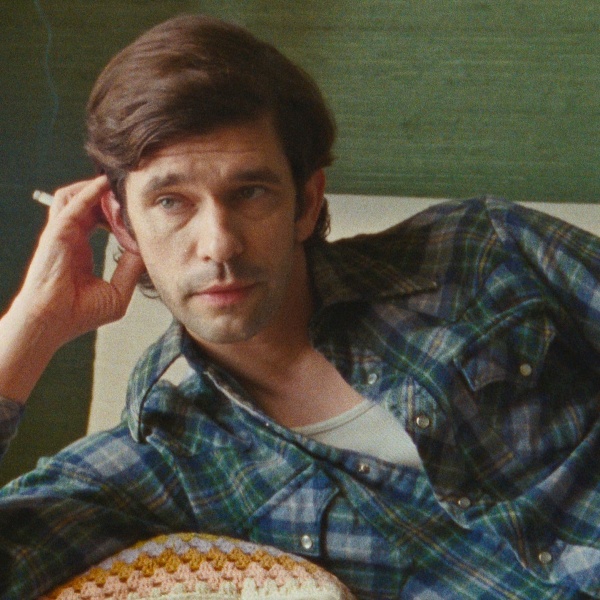

Throughout “Nightbitch,” a fair bit of the observational comedy is carried through the editing rhythm. So is the dramatic tension between the mother and her husband (Scoot McNairy). Heller scripted the dialogue and structured the coverage so that the film always emphasizes the emotional undercurrent of a relationship — whether things are about to erupt in anger or are slow and simmering, where what’s not being said is key.

“I do lead with hearing things. I have rhythms in my head. I think it comes from being a theater actor,” Heller said. “Especially with dialogue, I really hear the rhythms of dialogue and the build of dialogue in my head. And then the visual elements kind of come second to me, which I don’t think is typical.”

Heller marshals all the elements in “Nightbitch,” visual and sonic, to lean into the mother’s emotional experience, rather than the film’s flashier genre elements. That’s a pretty bold move in an environment, even awash in high-concept IP as we are, where there are fears about audiences ever having a moment of uncertainty. Heller felt she really had to protect the film from good-intentioned notes that would muddy the emotional throughline with too many magical mechanics.

“It’s not like anybody is trying to mess up your movie. Everybody’s trying to help, but you have to learn how to interpret what’s going to be a helpful note and what’s not,” Heller said. “‘Like, maybe we should have a bell go off every time [the mother’s] in a fantasy so we all know it’s a fantasy moment.’ I had so much fun in the shooting of this moment playing with her experience and not knowing at times whether what she’s experiencing is real.”

That uncertainty resonated with Heller’s own experience of the extreme fatigue and mental anguish that are just a natural part of parenthood and long-term relationships. The more truthful the experience, the more audiences can connect with it, too.

“I tend to believe audiences are smart and can figure things out and lean in more when things leave a little bit to be figured out or interpreted. And I make movies for people who are smart,” Heller said.

“Nightbitch” is now in theaters.