Without Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the films and career of Martin Scorsese would be very different. “Mean Streets” would be less red (thank those titular “Red Shoes”), the title fight in “Raging Bull” wouldn’t have been preceded by that thrilling oner (thank the duel in “Colonel Blimp”), and we wouldn’t have that audacious flash of yellow in “The Age of Innocence,” an idea swiped from the red-hot climax of “Black Narcissus.”

Scorsese has always been admirably honest about his tendency to steal from the best, and “Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger” is at its most fun when Marty talks the audience through how the ironic filmmaking duo’s most striking images reshaped the canon. And what — to him — ultimately made them worth stealing.

These seemingly spontaneous moments are well-illustrated by director David Hinton, a BAFTA-winning documentarian who also made an episode of the BBC’s South Bank Show about Michael Powell in 1986. Much of “Made in England” is drawn straight from that.

By the time Hinton’s first offering on the filmmaker arrived, Powell was a recognized force in world filmmaking (Scorsese’s public advocacy helped, while Francis Ford Coppola had even hired him), and comes across as jolly and convivial. He was never a celebrity, nor ever really a “name” in British film, like Alfred Hitchcock or Carol Reed or David Lean. But in that hour-long TV special, Powell is a settled, upfront character clearly pleased to have his moment in the sun.

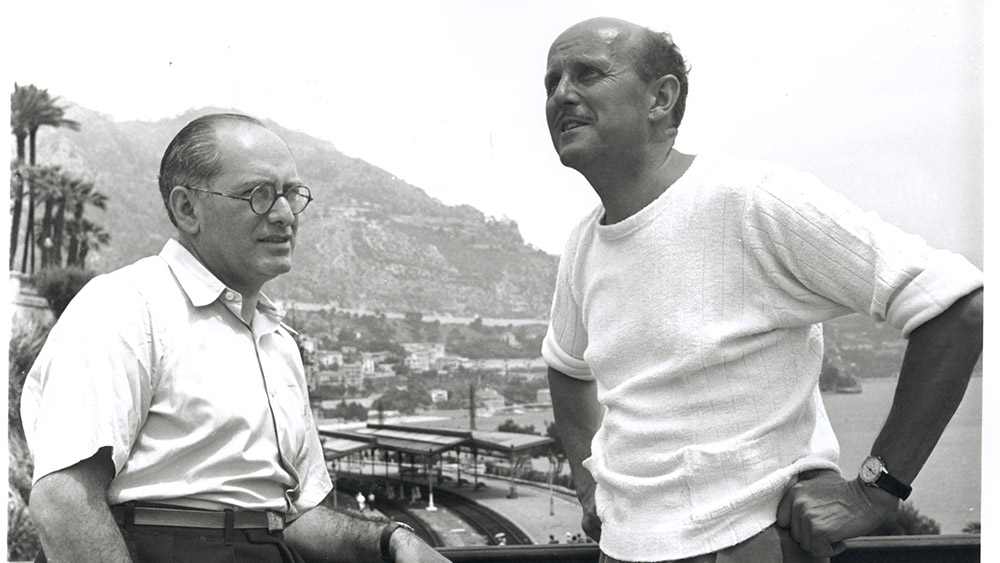

Powell visits old haunts, including the studio office where he first met Emeric Pressburger, a shy and intense writer whose interiority made a healthy contrast to Powell’s bluntness. And Pressburger’s status as a Jewish refugee from Hungary who fell in love with Britain allowed Powell to rediscover his own love of English-ness. Like Martin Scorsese, who in trying to explain why he loves their films says, “I don’t really know what English romanticism is,” Powell and Pressburger’s sense of style came entirely from within. There was nothing academic, or even particularly intellectual, about it.

Powell’s most insightful line is probably his explanation of why he relates to Colonel Blimp, the ’30s newspaper caricature for the Little Englander mentality that Powell and Pressburger (and an incredible Roger Livesey) turned into a deeply felt wartime tribute to their nation, native or adopted. “Sentimental,” Powell says. “Loves women and dogs.”

The other reason Powell is so perky in that special is that he wasn’t far off being a newlywed, having tied the knot with Thelma Schoonmaker — Scorsese’s longtime editor and the source of plenty of his Powell and Pressburger-esque dynamism — in 1984. They would remain married until his death aged 84 in 1990.

Combining scripted, video essay-style analysis next to Powell and Pressburger’s films with Scorsese’s random observations, “Made in England” is chronological and very watchable. Its most interesting theme is the idea that, for Powell and Pressburger, representation was almost always endorsement. They made films about people they cared about, and promoted values they felt were important for moviegoers to be aware of.

That gave films like “A Matter of Life and Death” and “A Canterbury Tale” something of a sermon-like quality, which opened them to criticism. But, at least until Powell made the radical drama “Peeping Tom” years after his bond with Pressburger had ended, neither had any interest in making the sorts of scuzzy films of cautionary tales with which Scorsese made his name.

In a world defined by chaos and where newsreels made the cinema a kind of font of truth as much as a centre for frivolities, they associated filmmaking with a great ethical responsibility. Their distinct style and moralism might have contributed to Powell and Pressburger going out of fashion as neo-realism bred moral relativism in cinema and more educated audiences felt they could make up their own minds. But it makes Powell and Pressburger’s films even more interesting to watch now.

One quote from Hinton’s South Bank Show episode that didn’t make it into “Made in England” is Powell’s assertion that documentary-making is for “out-of-work poets.” There’s consistently a sense that the archive-explanation-archive format is a million miles away from the fluid musicality that made Powell and Pressburger’s best work so unforgettable.

It’s also in that documentary grey zone of not knowing quite who it’s for — those who’ve seen a couple of Powell and Pressburger films and want to watch more will find its analysis is a bit thin, opting for accessibility rather than treading new ground or offering an original explanation for the duo’s greatness. For those who haven’t seen any Powell and Pressburger films but are enticed by the prospect of Martin Scorsese waxing lyrical about his idols, and one who became a personal inspiration too, it all but recounts what happens in each film.

That might make it more accessible for those not familiar with the pair’s films, but it stops “Made in England” from being a particularly valuable resource to those who are. It ends up a stellar example of what in Britain would play on BBC Four: polite, rarely profound, and packed with facts. It’s unable to channel the essence of what made Powell and Pressburger’s films unforgettable. Sadly, it’s not really trying.

Grade: B-

“Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger” premiered at the 2024 Berlin International Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.