Floating 10 miles beyond the tip of Great Britain like a barren moon that’s been anchored to the rest of the world by a rusty chain running beneath the North Sea, the Orkney Islands are a place so primordial and extreme that even the scientists who live there fall back on folklore to explain it. Maybe the silent tremors that vibrate through the land are caused by the impact of ocean water crashing into underwater caves — but it seems just as plausible that they might be produced by a buried dragon the size of the entire world unfurling its massive tail. Maybe the poor souls who drown off the coast are truly lost and gone forever, but on this blustery archipelago — where the winter breeze can only be measured in scenes from “King Lear” — it doesn’t seem too far-fetched to believe that the dead turn into adorable selkies who wash to shore and dance naked on the beaches in the moonlight.

After all, there must be some kind ofmagic that holds people there, even if that magic is fringed by a constant threat of madness; a madness that Orkney is liable to trigger but unable to treat, as the nearest facility for mental illness is located all the way over in Aberdeen. On the night that Rona was born, her bipolar father had to be airlifted off the islands amid a manic episode. When confronted by the wildest extremes of their own nature, the people of Orkney — as rough and jagged as the land, but absent the legends invented to explain it — have no choice but to go somewhere else. To leave. At least until the wind blows them back home.

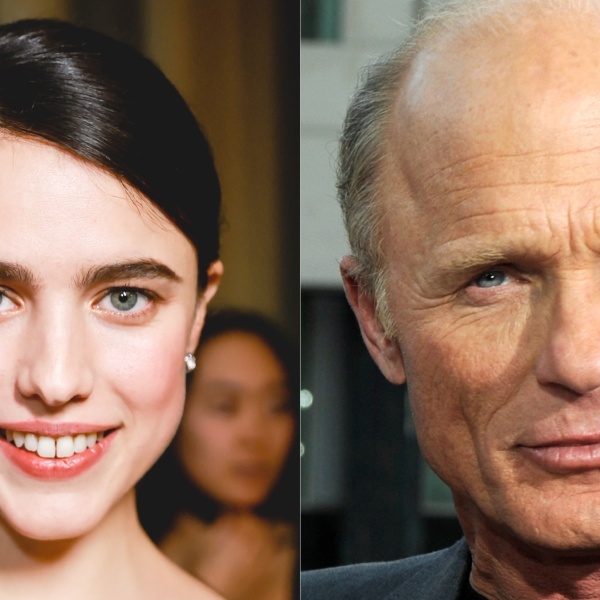

Most of this is covered in the first two pages of Amy Liptrot’s “The Outrun,” and the craggy, elemental, and heavily fictionalized recovery drama of the same name that German filmmaker Nora Fingscheidt (“System Crasher”) has adapted from Liptrot’s memoir sets the scene almost just as fast. The first 10 minutes feel like walking backwards into a hurricane, as a disorienting rush of Scottish legend, Saoirse Ronan voiceover, and chaotic handheld cinematography shipwreck Rona on the shores of Orkney Mainland after the wayward biology student has almost drank herself to death in London. Sober for more than 100 days by the time this non-linear story begins and desperate to wrestle control over the storm that’s still raging behind her eyes, Rona retreats to the harshness of her hometown in the hopes that her own extremes might be put into perspective by the furious ocean tides. She’s drowned at the bottom of a million different bottles, and now it’s time to be reborn.

A towering piece of landscape art when compared to the 85-minute doodles that tend to premiere at Sundance these days, “The Outrun” is far too grounded a film to get swept away by the magical-realist spirit that fringes Rona’s existence, (a spirit kept alive by flights of fancy, quirks of nature, and a few euphoric microdoses of colorful animation), but this rugged character study is nothing if not a story about the human capacity for transformation — even if Rona only turns into herself. If that process is as subtle and violent as watching the sea erode a rock into a cliff, Fingscheidt’s nonlinear approach allows the film to ride the tidal rhythms of addiction, while Ronan’s committed performance churns those ebbs and flows into a widescreen journey that earns its epic backdrop.

Absent a conventional plot, “The Outrun” is mostly sustained by the brisk and invigorating pleasure of watching Rona become a part of that backdrop — it’s the rare film that grows richer as its heroine is flattened into the scenery. Key to that effect is Fingscheidt’s clever decision to invert the visual metaphors that tend to suffocate character studies like this; if Orkney is initially framed as a reflection of Rona’s inner volatility, “The Outrun” gets even more compelling as Rona becomes a reflection of Orkney’s eternal perseverance. That reversal is baked into the source material, some of which appears verbatim in Liptrot and Fingscheidt’s script as part of Ronan’s voiceover (“My body is a continent… Lightning strikes every time I sneeze, and when I orgasm, there’s an earthquake”), but this film also finds more ambient and instructive ways to make Rona feel like an extension of her environment. To dramatize her personal geology.

The most crucial of them all is the deep blue dye that runs through Ronan’s hair, which Fingscheidt uses as a North Star to help the audience find themselves in the story. In the flashbacks, when Rona is getting blackout drunk at a nightclub in Hackney or sneaking off for a bottle of wine in the bathroom of the apartment she once shared with her ex-boyfriend (Paapa Essiedu), her hair is almost as blue as her eyes. In the present day scenes, where Rona tolerates her ultra-religious mom (Saskia Reeves, whose character is born again in a different sense), treads softly around her still-fragile dad (Stephen Dillane), and takes a volunteer job trying to find corncrakes for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, what’s left of the dye clings to her tips like the dregs of her past.

“The Outrun” would be easy enough to follow even without this extra flourish (no one is going to watch Ronan pull a newborn lamb out of its mother’s womb on a windswept farm in the middle of nowhere and wonder if Rona is still in London), but it effectively situates Rona as an expression of the elements rather than a creature who’s at their mercy. She is time, just as her “freckles are famous landmarks” and her “breath pushes the clouds across the sky.”

In that light, “The Outrun” is never more intimate, unstable, or affecting than it is during the moments when Rona feels unstuck in time, lost somewhere along the circular path that runs between the past she’s dying to escape and the future she’s living to find. There’s an anachronistic charge to watching Rona walk around her father’s rustic farm with a pair of wireless headphones that are blasting EDM into her brain, and Fingscheidt’s characteristically frenetic camerawork — while more extreme during the flashbacks — further intensifies the strange vertigo that Rona suffers from bringing adult crises back to her childhood home.

But it’s Ronan who becomes the film’s most dizzying and mesmeric effect, as the actress — who hasn’t starred in a contemporary-set movie since 2015’s “Stockholm, Pennsylvania,” despite bringing a peerlessly vital nowness to every part she plays — feels like an anachronism unto herself in such a modern role. If the opening scenes made me nervous that Ronan’s screen presence might be a little too “nice” to buy her as a believably violent alcoholic, those doubts were soon dispelled by the voraciousness that she injects into each scene; the way she fumbles through Rona’s overeager flirtation with the first guy she meets back in Orkney, or eyes an errant glass of red wine with vampiric bloodlust. Rona is a product of her environment, and Ronan — like Orkney — is able to make even her most dangerous extremes feel like a reflection of inner strength.

Ronan is alive and responsive in a way that prevents her from ever feeling like a film character, even when “The Outrun” gets stuck in the familiar rut of addiction dramas, and its erratic timeline starts to feel like an exasperating distraction from the broad strokes of a story we all know far too well. Fingscheidt can only transpose so much of Liptrot’s singular internal monologue, and this adaptation of her memoir — for all of the mileage that it gets out of its cast and locations — sometimes drifts over the thin line that separates truth from cliché.

But even the most predictable ups and downs of Rona’s long recovery are eventually revitalized by where that path leads her, and “The Outrun” gets better as it goes along because Fingscheidt trusts that it will be even more compelling to watch Ronan harness her character’s power than it is to watch her fall prey to it. We know that Rona is going to relapse at some point, but “The Outrun” doesn’t take any ghoulish pleasure in that inevitability. Rather than framing it as a moment of weakness, this movie uses it as an invitation for Rona to discover new strength; for her to embrace the tempests that rage around and inside of herself, and push deeper into them both as she trades the Orkney Mainland for even more forbidding environs.

By leaving her island home in favor of an island off an island off an island off an island, Rona discovers that she’s more connected to the land than she ever thought possible. She is every bit as real and eternal as the other legends that have taken root in the soil around her. She is a living explanation for a world of unfathomable power. And by the end of this movie you can feel it flowing inside of her, the energy of the ocean waves entering her body with the same transformational force that it crashes into the shores of Orkney and reverberates through the Earth like a dragon so vast it can hardly appreciate its own scale.

Grade: B+

“The Outrun” premiered at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.