2020 still has its hold on us, and will for a long time.

Not just because COVID is still circulating, but because of the emotional fallout of that time that so few of us seem to have processed. Grief is something Americans, in particular, have a hard time with. Nations as varied as Italy, China, and Kazakhstan have had National Days of Mourning for their COVID victims. Spain had 10 days of official national mourning. Mexico, a month. The U.S. had over a million victims, and there’s been no such nationwide remembrance.

Luke Lorentzen’s documentary “A Still Small Voice” is so powerful because, even though it’s not really about Covid at all — the word is only mentioned a couple of times in its entire 93 minutes — it’s about the processing of strong emotions American culture is all too likely to avoid through denial, distraction, and workaholism. Almost therapeutic, the film, which made the Oscars documentary feature shortlist, follows Margaret “Mati” Engel, a chaplain completing her residency at New York City’s Mt. Sinai hospital, from September 2020 (when filming began) until she leaves the program in the summer of 2021. “I do very much see ‘A Still Small Voice’ as a document of a certain feeling that was very pervasive through the pandemic,” Lorentzen said in an interview with IndieWire.

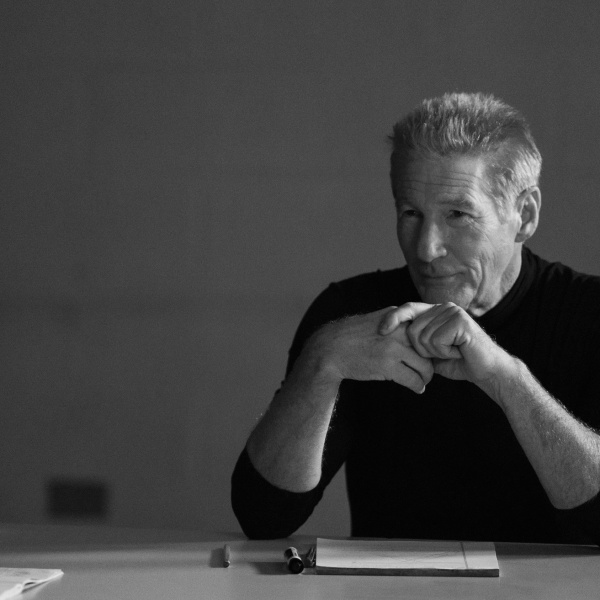

The film also focuses on Engel’s supervisor, the Episcopal minister David Fleenor. Lorentzen got extraordinary access from Mt. Sinai to follow them, and other members of their team, as they console patients who are dying, and the loved ones of those who’ve already passed on. Fleenor remarks early on that their approach is the opposite of the usual “Don’t just stand there, do something!” that’s so typical of action-oriented American culture. They want to embrace the idea of “Don’t just do something. Stand there.” Watching the film is a cathartic experience, a way of processing emotions many of us didn’t even know we were still holding onto. It almost makes you feel more emotionally intelligent by the time the credits roll.

There have certainly been documentaries about Covid before, such as Nanfu Wang’s “In the Same Breath.” But “A Still Small Voice” achieves something deeper: it’s about mourning tremendous loss and dealing with extraordinary change, like that provoked by the pandemic. This did not exactly make for an easy sell, however.

“It was never a film that I felt immediately comfortable pitching to people, even just friends or family at parties,” Lorentzen said. “Just the one-liner was always a mouthful for me to get out.”

It’s hard to sum up the impact of several moments in the documentary: A patient dying of lung cancer who talks about how she feels “distant” from her disease — and who gives the film its title, referring to the voice within — who Lorentzen said died shortly thereafter; the young parents of twins, grieving the loss in childbirth of one of the newborns, who have Mati baptize the dead infant; Mati praying with a cancer patient who’s suffered an astonishing array of maladies. There aren’t many of these moments, but each feels emblematic of something so much bigger, something we can all relate to.

And since most of these are conversation scenes, Lorentzen, shooting everything as a one-man crew, found intimate and creative ways of covering them — especially since most people are wearing masks when we see them. During a long conversation, he’ll often cut to a shot of the speakers’ hands.

“I had a real insecurity about people wearing masks throughout the filming,” he said. “I’d never seen a film where people would wear masks for the majority of it. So I did everything I could to, I guess, on one hand lean into that, but look for all of the smaller ways that emotions were expressed. The big one was eyes. I think it’s a film of people’s eyes and really trying to have both eyes in every frame and really focus on them in a big way. There were smaller pieces of body language that were super telling, and hands were one of them.”

The 30-year-old filmmaker previously brought “Midnight Family,” a documentary about a paramedic team in Mexico City, to Sundance in 2019. Even before Covid hit a year later, he’d been thinking about a film dealing with the aftermath of the kind of acute crises and medical traumas depicted in that film. His sister is a hospital chaplain and introduced him to the unique “interfaith and no-faith” work of her field, where chaplains essentially have to embrace all religious practices of every faith in order to help people of every background. It’s an “all religions are true” mindset that feels exactly like the antidote to our moment of division without ever diving into fridge-magnet platitudes.

“Part of the residency was teaching these young chaplains how to understand all belief systems, all of the ways in which people make meaning, understand themselves, understand the world around them,” Lorentzen said. “And that was a boat I could very easily get in. There are so many parallels between what chaplains do and what I, as a documentary filmmaker, am most interested in; relating to people, hearing and capturing stories, finding vulnerable, intimate, close connections.”

Lorentzen spent time filming all the members of Fleenor’s team, amassing somewhere around 500 to 600 hours of footage — or 150 days over nine months — before whittling it down to just Engel’s story, and her working relationship with her boss, Fleenor, which is fraught, as both have different strategies to deal with what is strongly emotional labor. Her arc is very symbolic of larger trends in society, with even her ultimate choice to leave day-to-day hospital work — despite being eminently gifted at chaplaincy — somewhat symbolic of the Great Resignation that followed Covid, as people reassessed their lives.

In going from 500 or 600 hours of footage to just 93 minutes, Lorentzen felt one guiding principle was essential: He would not have final cut. At any time, he’d allow the participants in the documentary to pull out if they wished. “It didn’t feel right for the normal power dynamic of a director having final cut to apply in a context where people were so vulnerable and so generous with what they were willing to share,” the director, who filmed everything at Mt. Sinai by himself, said. “Being two years into a project where anybody can pull out of it is risky, but it enabled a certain intimacy that otherwise just would not have been possible. We had two scenes that we had to pull out of the film in the very last month of editing. At the time it felt very, very stressful. Looking back, I’m proud of in a certain way that we were able to follow through with this.”

That strong feeling to commit to this sounds like it was Lorentzen listening to his own “still small voice.” Oh yes, about that title: “I personally think of one’s ‘still small voice’ as the deepest, truest inner self. It’s the gut feeling that tells me what I care about most.”

We all face grief, we all lose loved ones, we will all die. The experience of the patients and their families in “A Still Small Voice” is as universal as can be. And yet it feels like a revelation to see this onscreen. We don’t often see in movies a real processing of grief, other than showy death scenes here and there. “It’s been at almost every screening I have people either sharing in the Q&A or coming up to me afterward mentioning a life’s moment or experience the film touched on,” Lorentzen said. “There are bits and pieces of this story that audiences have connected to with such a range of past life experiences. Hearing all of these personal reactions and seeing people see and understand themselves and their past experiences in a new light has been a true gift for me through the process of sharing the film.”

Watching “A Still Small Voice” can be tough, because it’ll undoubtedly summon up memories of loved ones you’ve lost throughout your life too.

But how much better to remember them.