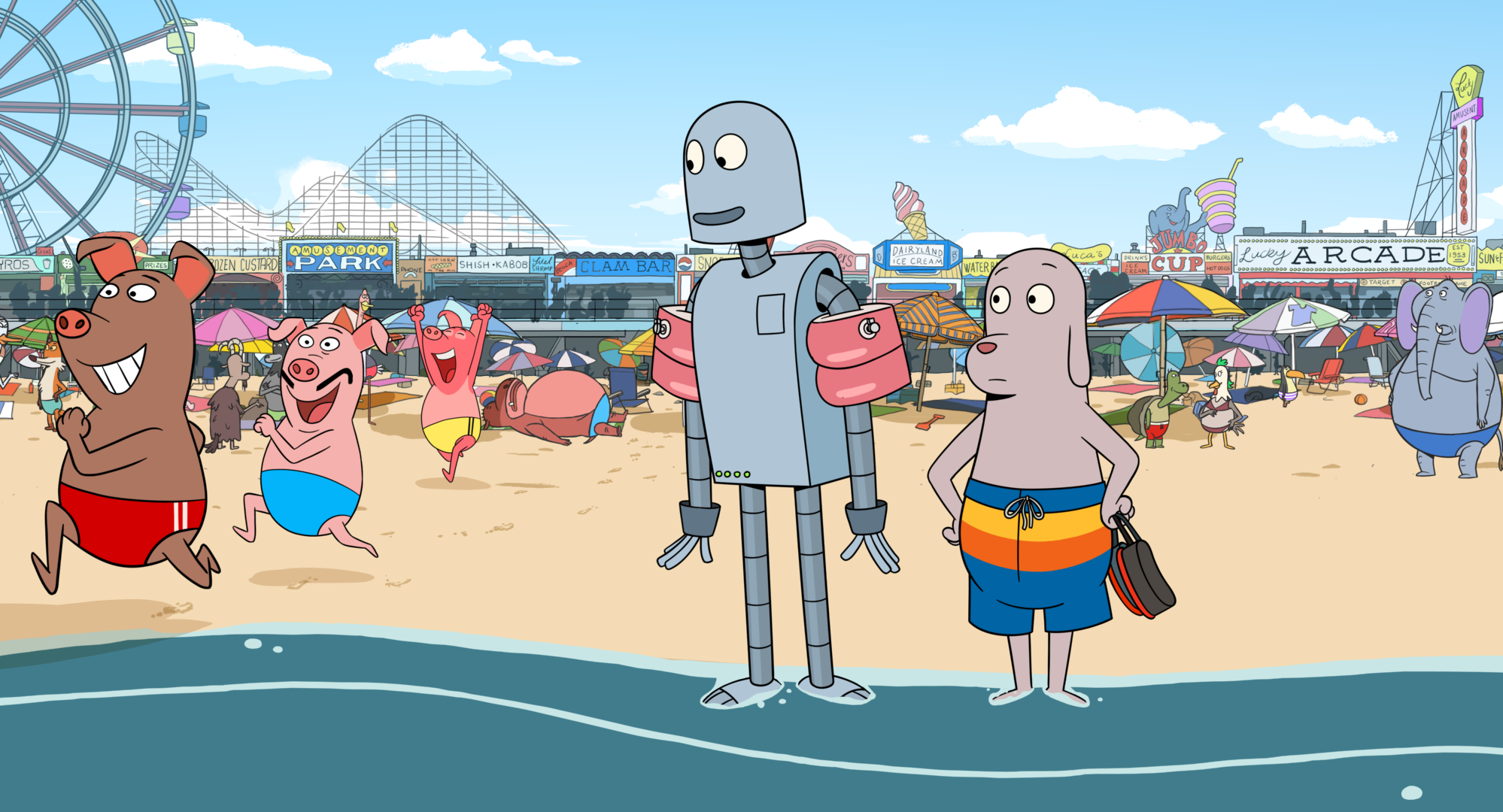

Pablo Berger’s “Robot Dreams,” which gets a theatrical release from Neon at an as-yet-unannounced time this year, was one of the animated delights of 2023. The Spanish/French hand-drawn dramedy (adapted from Sarah Varon’s wordless graphic novel) concerns the bittersweet friendship between lonely Dog and Robot, which he buys for company, in a version of ’80s Manhattan populated with animals. It’s garnered awards buzz in a longshot quest for an Oscar nomination this season.

After premiering at Cannes, “Robot Dreams” earned the Annecy Contrecham Award along with The Animation Is Film Festival’s Grand Jury Prize. It was also selected as the runner-up for Best Animated Film by both the Los Angeles and Boston Film Critics groups.

Although the Spanish director was enamored with the graphic novel when he read it in 2010, he didn’t consider turning it into an animated feature until after making two live-action films, “Blancanieves” and “Abracadabra,” and meeting with Varon in 2018.

Afterward, Berger couldn’t get “Robot Dreams” out of his mind: the loneliness of Dog, Robot’s eternal optimism, the crowded East Village that brought back memories of when he lived there, the melancholy separation that leads to new adventures and friendships, a surprise finale that brings a wave of nostalgia. It cried out for the physical humor of Jacques Tati, the sublime emotion of Charlie Chaplin, and a meticulous ’80s world-building.

“But I love animation and I needed films that I could connect with,” Berger told IndieWire. “And, for me, that was ‘The Triplets of Belleville’ by Sylvain Chomet.” The mixture of pantomime, song, whimsy, sadness, and absurdity (not to mention a dog) became his animated model.

“His movement, and all the detail, and all the background characters are always doing something,” Berger continued. “And that’s a very rare thing in animation, And, of course, Studio Ghibli was key. We were always looking at Ghibli because they have an answer for everything. But I connect a lot with [Isao] Takahata. Miyazaki’s fantastical but Takahata, no. I like his storytelling in ‘Grave of the Fireflies.’”

Berger nearly made it at Cartoon Saloon (“Wolfwalkers,” “The Secret of Kells”), the Irish Ghibli, but that fell through because of COVID-19. So he set up two pop-up studios in Madrid and Pamplona with 100 artists for his animation debut. The producer was Arcadia Motion Pictures (“Ozzy – Bad Dogs”), the animation director was Benoît Feroumont (“The Secret of Kells” and “The Triplets of Belleville”), and the art director was Jose Luis Agreda (Cartoon Saloon’s Disney+ series “Viking Skool” and “Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles”).

“Coming from live action, I knew every day where I wanted to put the camera,” Berger said. “I’m very involved with the storyboards, and I had my art director with me and Maca Gil from Cartoon Saloon was the head of story. But I did something that you don’t normally do, I had my animation director beside us doing thumbnails so the art director would know where the camera was going to be from the beginning.”

Berger wanted the animation to evoke the simple graphic novel aesthetic with clean graphic lines, flat colors, and sharp focus. The characters were true to their literary spirit, but their animated performances were dynamic. Berger modeled the dog after himself and the robot after Agreda. Without speaking, they could be very expressive with their eyes and limbs, and the robot moved 360 degrees. It was like silent cinema (“City Lights” was a key influence). Additionally, they were surrounded by hundreds of mixed animal breeds in this harmoniously integrated society, which was true to the East Village that the director remembered. They were character designed by Daniel Fernandez Casas (“Migration” and “Klaus”).

As for accurately evoking the period sights and sounds of the East Village (including fashions and product placement), the director relied on his wife and associate producer, Yuko Harami, to act as a location scout in collaboration with Agreda. “She was always providing the locations, the props, looking for where the film could take place,” he added. “Where does Dog live? Where does Robot live? What was a Radio Shack in the ’80s?”

It was important, though, to expand and invent ideas to create surprise and emotional depth. For example, a family of birds makes a nest on Robot while he’s stuck spending the winter alone on the beach, and he bonds with them. And how Robot dreams throughout. While this was obvious in the graphic novel, Berger imaginatively mixes reality with his dream states, resulting in a bowling scene with a snowman, an action scene in the Catskills, and a Busby Berkeley-like dance routine with flowers at the beach. This evokes “The Wizard of Oz” when the director flips a billboard to transition the two environments.

“That’s the way I write,” added Berger. “I let myself go with the subconscious to bring visual ideas, and then I try to bring some order to the chaos. And for me this book allowed me to be like a jazz musician. The book was the melody, and I imagined that I was John Lurie [co-founder of the Lounge Lizards]. I found the melody and played the melody but then I improvised and found my way back to the melody.”

In fact, Berger’s most inspired idea was choosing Earth Wind & Fire’s iconic “September” as his joyous anthem for Dog and Robot. When the song bursts out of the boom box, it brings the East Village together. “‘Do you remember, 21st night of September?’ That’s my daughter’s birthday and we had to find the budget to license it. There was no Plan B.”