Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2023 Venice Film Festival. A24 releases the film in limited theaters on Friday, October 27, with expansion to follow.

Priscilla Presley only had a few precious lines in Baz Luhrmann’s “Elvis” (a delirious biopic whose title always feels like it’s missing an exclamation point), and even fewer of them were memorable in the slightest. But, a little more than a year since that movie came out, one bit of Priscilla’s dialogue continues to stay with me for how succinctly it crystallized the film’s conception of her. “I am your wife!” She yells at Elvis, as if he doesn’t know. “I AM YOUR WIFE!” That was all she was in that story. It was no different than if Vernon Presley had screamed “I AM YOUR DAD!” or if Colonel Tom Parker had bellowed “I AM YOUR MANAGER!” (which he probably did).

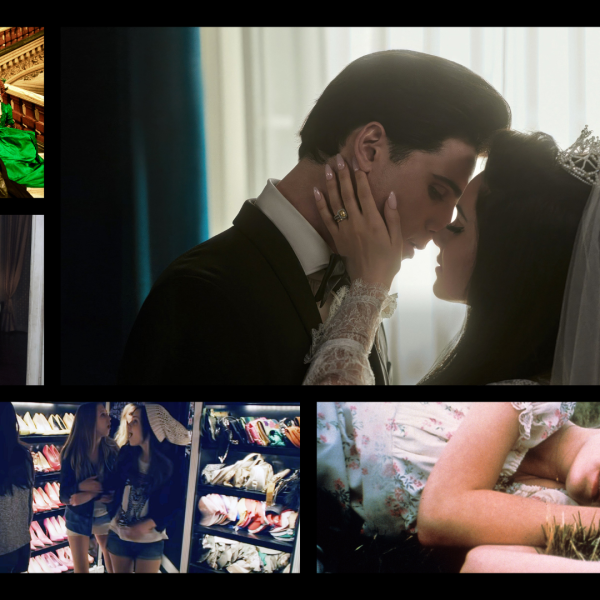

And that’s fine, I suppose — “Elvis” had its own agenda, and its namesake’s only wife didn’t play a large part in it. But Luhrmann’s spasmodic rhinestone spectacle may have finally served its purpose, as it now provides helpful context for a new film that another major artist has made about The King’s one-time queen. Which isn’t to suggest that Sofia Coppola’s soft and muted “Priscilla” should be seen as some kind of rebuttal to last summer’s orgiastic blockbuster, but rather to reaffirm her decision to frame this claustrophobic marriage story as a gradual process of separation. Not just Priscilla’s separation from Elvis and the endless shadow of his celebrity, but also her separation from her parents, from her own iconography, and from everyone and everything else that tried to define her before she was able to define herself.

Of course, Coppola was never going to approach this story in any other way. Long compelled by the negative space between young women and the worlds they inhabit (a gap that “The Virgin Suicides” described as “an oddly shaped emptiness mapped by what surrounded them, like countries we couldn’t name”), Coppola has made a career out of freeing privileged girls from gilded cages; girls who are desperate to escape the sense that they’re merely disguised as themselves, always watched but seldom seen. From “Lost in Translation” to “Marie Antoinette,” her films have often framed marriage as the purgatorial first step in a heroine’s path towards actual personhood. Her latest feature makes it impossible to shake the feeling that Sofia Coppola would probably have been moved to invent Priscilla Presley if Priscilla Presley hadn’t ultimately found a way to invent herself.

Comparisons to the more opulent and electrifying “Marie Antoinette” are inevitable, as both movies are about teenage girls who are trying to appease their kings, and both movies look at their hermetically sealed historical figures through a (somewhat) modern lens that sees through decades or centuries of mythmaking in order to render the emotional reality of their respective situations. But from a certain perspective, “Priscilla” is also the polar opposite of Coppola’s 2006 masterpiece. While Marie Antoinette was forced to Versailles against her will, Priscilla Presley’s ultimate dream was — like many girls her age in 1963 — to live in Graceland as Elvis’ wife. And while Marie Antoinette spent the brunt of her short life struggling to reconcile a sense of personal identity with the one conferred upon her by the royal palace, Priscilla Presley, who’s still alive today (and an executive producer on this film), spent the brunt of her short marriage realizing that she didn’t have to.

“Priscilla” may not be one of the better movies that Coppola has ever made — it’s vague where her previous coming-of-age stories have been knowingly precise, scattered where its predecessors revealed new insight with each scene, and gloomy where those other films were galvanized with pockets of light — but it stands apart from the rest of her work as the uniquely sensitive and self-honest portrait of a girl who starts to realize that she may have outgrown her greatest fantasy.

One of Coppola’s signature pre-title sequences notwithstanding, the movie first introduces us to Priscilla in the fall of 1959, when she’s living with her parents on an Air Force base in West Germany. Played by a sweet and recessive Cailee Spaeny, the Priscilla we meet is 14 going on 12 — a mousy young military brat whose father would probably kill any man who dared show her the slightest hint of sexual attention. But 24-year-old Elvis Presley, stationed in Bad Nauheim at the height of his fame, isn’t just any man.

Played by “Euphoria” star Jacob Elordi, whose immediately convincing take on the character is more human and heartsick than Austin Butler’s performance ever was (less a dig than a job description), Elvis sparks to the underage Priscilla at a crowded house party because she reminds him of home. That loaded come-on proves typical of a film that shrewdly hears all of its dialogue in stereo, through Priscilla’s ears on one end and our own at the other (Coppola’s dialogue-light script is based on Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir, “Elvis and Me”).

“You’re such a baby,” Elvis coos approvingly at his underage new crush, not teasing her so much as fetishizing her innocence. Grieving his late mom 3,000 miles from Graceland, this Elvis seems tired of being one of the planet’s biggest sex symbols, and that he’s already losing touch with any of the real things in this world. We sense that he sees the button-nosed Priscilla as a tether of sorts, one that will keep him from being subsumed into the siren’s song of his own image. She’s all too happy to oblige.

Coppola is as sharply attuned to the differences in age and power between these two people as any filmmaker ever has or could be, and while Elordi’s towering height might be as unrealistic as any of the subtly anachronistic needle-drops that litter the movie (The Ramones’ “Baby I Love You” and Tommy James and the Shondells’ “Crimson and Clover” being two obvious standouts), the film takes full advantage of how small Priscilla always seems beside him. Elvis looms so large that his child bride will be able to feel his shadow being cast over Graceland even when her husband is off in Hollywood sleeping with various starlets and trying to become the next Marlon Brando.

But Coppola isn’t in a hurry to get to that part. She delights in the early years after Elvis and Priscilla’s whirlwind romance — after he went back to his throngs of screaming fangirls in the States and Priscilla was given the impossible task of going back to her life as an ordinary high schooler. It’s like Cinderella being forced to sweep the attic again after her magical night at the ball, and hearing all about her prince’s love affairs every time she turns on the radio. But this Cinderella’s prince is the King, and despite ample opportunities to exploit his loyal subjects he never forgets about the girl he met in Germany.

When the call finally comes for Priscilla to join her man in Memphis, she thinks she’s being summoned back into a fairy tale, when in reality she’s effectively being adopted as a housecat — a dynamic he tries to diminish by giving Priscilla a dog. Coppola isn’t shy about how Elvis begins to groom his girlfriend (a recently loaded word that can’t be avoided here), but she’s never painted any of her characters as a victim and she isn’t about to start now.

Priscilla’s first years at Graceland are all part of becoming the fantasy, a process that entails being transformed into Elvis’ perfect woman even as she’s hidden away from the public eye with the help of his omnipresent posse of pistol-packing goons. Priscilla gets the big hair, packs away all of her nice prints, and dresses herself in various shades of blue because Elvis insists that it’s her color (the very first shot of the movie, which comes to assume an undertone of rebellion in hindsight, would suggest that Priscilla disagrees).

In the eyes of a filmmaker who’s always used exterior aesthetics to access the interior lives of people who aren’t permitted to have them, Priscilla’s makeover is a violently oppressive negation of her selfhood, and it doesn’t stop with her style. Elvis gets her hooked on the same uppers and downers that he uses to maintain the rhythm of his life; he later gifts Priscilla an expensive watch, oblivious to how useless it might be in the purgatory he’s created for her.

It goes without saying that Elvis doesn’t come off so great in this movie, but “Priscilla” never renders him as a monster, even after he starts throwing chairs and getting into scandals. On the contrary, the film paints him as a (very flawed) real person who’s similarly entombed by the image that’s been created for him. Elordi and Spaeny don’t spend a ton of screen time together — Elvis doesn’t even touch Priscilla until they get married, despite her pleading — but they look at each other with mutual sympathy when given the chance. It’s the mutual sympathy of two people forced to navigate larger-than-life roles as two people forced to navigate larger-than-life roles.

And while the fragmented nature of Coppola’s film makes it frustratingly difficult to chart how Elvis and Priscilla begin to change (far more elliptical than “Marie Antoinette” or even “Somewhere,” this herky-jerky movie is structured with the elusiveness of a memory play), that frustration can be offset by the sense that neither of them really change that much. Coppola’s cloistered vision of Graceland, which seems much smaller on camera than it is in real life, adds to a pervasively inert sense of stasis.

Surrounded by a pink fieldstone wall, the house is a sanctuary that’s separate from the world — the eye of an unmoving hurricane that’s always watching her. An occasional on-screen title updates us on the year, but the only real way to measure the passage of time is by watching the decor wilt into kitsch. That Elvis’ estate denied Coppola the rights to most of his music works to the advantage of a movie so keyed into how removed Priscilla felt from anything that was happening in her husband’s career.

Similarly, that Spaeny never seems to age over the 14-year span of the story only reaffirms the atemporality of Priscilla’s existence, as does the blankness of her performance and the repetitiveness of Coppola’s screenplay, which denies character and actress alike with any particularly dramatic opportunities to depict personal growth. “Marie Antoinette” seems like a broad melodrama compared to impressionistic minimalism on display here.

There are a handful of uniquely expressive moments when Coppola plays to her strengths, such as the late scene in which Priscilla applies her eyeliner with the righteous purpose of a woman creating her own image, but it’s otherwise hard to track how Priscilla finds herself. We know that she’ll ultimately braid a ladder that she uses to climb over the castle walls and escape through the cracks of the fairy tale she’s been telling to herself since she was a tween, but in practice it just feels like she reaches the end of her rope when Coppola runs out of story to tell.

All the same, the movie saves its richest nuance for its final shots, which are set to a music cue that’s fascinatingly unambiguous about Elvis and Priscilla’s enduring affection for one another. Priscilla may outgrow her teenage fantasy, but that doesn’t mean she comes to hate the man who made all of her dreams come true. Fantasies aren’t real, but it’s better to let them die than to deprive ourselves from having them in the first place. While “Priscilla” leaves it open-ended as to where its namesake might go from here (the film, alas, ends about 20 years too early for us to see Coppola re-create the set of “The Naked Gun 2 ½: The Smell of Fear”), it’s enough to know that she’ll never have to say “I’M YOUR WIFE!” again.

Grade: B

“Priscilla” premiered at the 2023 Venice Film Festival. A24 will release it in theaters on Friday, October 27.