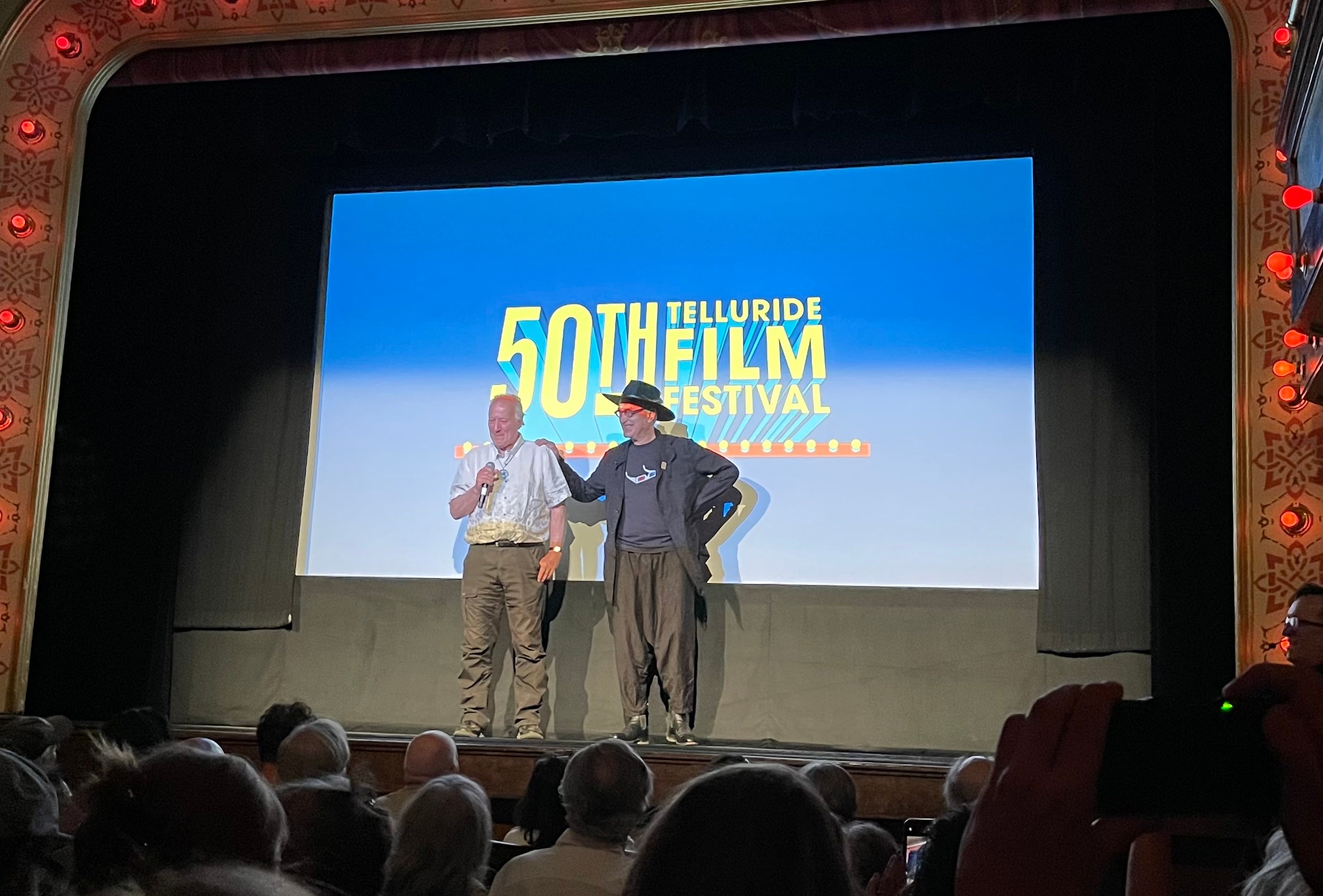

One of the pleasures of Telluride is watching a master auteur accept the Silver Medallion. Telluride Executive Director Julie Huntsinger was shocked to discover that in the 50 years of the festival, no Silver Medallion was ever awarded to German filmmaker Wim Wenders. So this year, he brought his two Cannes selections, 3D documentary “Anselm” (Sideshow and Janus) and Competition title “Perfect Days” (Neon), whose star Koji Yakusho (“Shall We Dance?”) won Best Actor at Cannes. Despite its German director, Japan has chosen to submit the film for the Oscar.

At Thursday night’s first tribute, Werner Herzog dug into his pocket to fish out the Silver Medallion, and placed it around his old friend’s neck. “The same time several years ago Tom Luddy put this on my neck,” said Herzog. “I kept thinking, ‘this is an injustice if you hadn’t received this medallion in 1978, and 1981, and 1995, and 2015.’ Because you’ve made one film more beautiful than the next. It is very strange.”

“I would have missed this moment,” said Wenders, whose sizzle reel ran from “Alice in the Cities” and “An American Friend” and “Wings of Desire” through his Oscar-nominated documentaries “Salt of the Earth” and “The Buena Vista Social Club.”

“All of a sudden you have two films in this year,” said Herzog. “The films are lively, courageous, beautiful, everything you wish to see in the theater. I’m absolutely proud and absolutely moved to give this to you.”

Wenders recalled first meeting Herzog when he was in film school in 1968: “This man was three years older than me. I was 23. For the first time we had a real filmmaker who had already made the movie none of us have made. And Werner came in front of us. And what did he say? ‘You poor suckers! Why are you wasting your time in film school? Go out and risk your life and make movies.’ I kept it in my mind and I realized breaking the rules was probably the best thing I could learn in film school.”

The director thanked the late Telluride founder Luddy for showing his early films and inspiring him to drive through the American West, which led to “Paris, Texas.” In his introduction, MoMa chief film curator Raj Roy placed “Anselm,” the 3D portrait of German artist Anselm Kiefer alongside Wenders’ other artist portraits of photographer Sebastiao Salgado (“The Salt of the Earth”) and choreographer Pina Bausch (3D “Pina”).

Wenders and Kiefer, it turns out, were both born in 1945, both grew up along the Rhine, and both recognized that as they were growing up in Germany, nobody was looking back at their recent history. “All the adults around us were very busy building a new country,” said Wenders. “And the condition for that building was forgetting the country, forgetting the past. And as kids you realize something is wrong. And of course, you don’t know. ‘What is it?’ And we shared that feeling. And my reaction was that from the beginning, I wanted out. And Anselm’s reaction was from the beginning, he wanted to discover what it was. And those two approaches made our lives.”

It took a long time to get “Anselm” made. The two men first discussed it in the 90s but backburnered it until they suddenly recognized “it was now or never,” said Wenders, who watched as Kiefer was lionized in America and demonized in Germany. “We found out that Anselm was a painter who always wanted to be a filmmaker. And I was a filmmaker who always wanted to be painter.”

Wenders discovered he knew nothing about the process of painting. “Especially not about the process of a painter who thinks that there’s nothing in the world that escapes the act of painting,” he said. “Anselm is a man who can paint the universe, the macrocosm, and microcosm of the atoms, and he can paint the history of mythology and religion and alchemy, any science and poetry. There’s nothing that he thinks is not worthy, and not incapable of pulling into his art. I was lucky to make that experience over three years and seven shoots with him.”

At the second tribute conducted by Pico Iyer, Wenders revealed that he had always loved American culture, music, Mark Twain, comic books. “I got hooked to this substitute culture that represented much more joy and freedom than whichever one I grew up with.” When he was studying painting in Paris he recalled going to the Cinematheque every day to see movies, over 1000 in one year, he estimated. After a full retrospective of the work of Anthony Mann, Wenders figured out how movies are made. “I understood the whole architecture of movies through this one director,” he said. “My love for the American West was there and I also understood that filmmaking was doable.”

He also fell in love with the cinema of Yazujiro Ozu, who partly inspired his portrait of a toilet cleaner in Tokyo, “Perfect Days.” Wenders was approached by screenwriter Takuma Takasaki to come to Tokyo and check out the 17 specially designed public bathrooms there. Wenders took the opportunity to visit one of his favorite cities and figured out that he could use the marvelously inventive toilets as a location for a fictional story, not a documentary, that he would write with Takasaki. He came to Berlin, and they knocked out the script in three weeks.

They wound up telling the story of a man who for whatever reason — there’s untold history behind him — chooses to lead a simple life. He has a six-day work routine: brush teeth, trim beard, grab a can of coffee from the vending machine, listen to 80s music cassettes in the car, meticulously clean toilets, eat lunch outside, take photos, enjoy the trees, wash up and soak at a bathhouse, visit the same neighborhood restaurant, and read literature when he’s home. On his day off, he cleans up his apartment, drops off his film rolls, picks up and sorts his pictures, and visits another restaurant whose woman proprietor sings for him. He’s a happy man who encounters various people along the way, including his runaway teenage niece, who sees who he is and appreciates him.

“He’s from a different world,” Wenders told me at Telluride. “But he does connect and he has something contagious about him for the young people who he meets in the film, he does gain their respect. Because he’s so convincing in his beliefs. I just wanted to make this man really rich and interesting and modest, and at the same time, full of something good. He’s a happy camper. He’s a man who enjoys his life. And as that has become such a rare thing today, we felt it was worth it. And the big idea was really that this is a man who totally lives in the present day. And who lives every moment and enjoys what he does. He doesn’t need more than what he enjoys. And he doesn’t want more.”

The movie is unaccountably moving. And clearly Koji Yakusho won Best Actor partly because of one extraordinary long close-up on his face while driving listening to Nina Simone’s “A New Dawn.” One minute he seems content, the next sad, the next happy again. “That was the last shot,” said Wenders, who shot the film in 50 days. “He would have this one moment when it came altogether. Almost a little bit of a regret. ‘Did I choose the right life or didn’t I?’ And then the realization, ‘I did.’

Also in Telluride is the Cannes documentary “Room 999,” a follow-up to the original 1982 “Room 666” in which 16 filmmakers talk about the future of cinema. Wenders is the only one in both. “So the future of cinema since then has already changed twice,” he said. “It’s still in your eyes, that’s what the future is.”