Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2023 Venice Film Festival. Netflix releases the film in select theaters on Wednesday, September 20, and it will be available to stream on Netflix on Wednesday, September 27.

Rumor had it that Wes Anderson’s “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” — the first of the four Netflix shorts the filmmaker has made from Roald Dahl’s anthology book of the same name — would be such a radically faithful adaptation of its source material that it would ironically feel like something altogether new. Lucky for us, that rumor was at least half true. Two-thirds true, even.

On the matter of fidelity, there can be no question. Running 37 minutes long at a full sprint from the moment it starts, “Henry Sugar” recites Dahl’s text almost completely verbatim. It starts, as all movies should, with Ralph Fiennes muttering to himself in a miniature recreation of Dahl’s study (I never really begrudged Anderson for being inspired by an anti-Semite, but even less so now that he’s cast Amon Göth to play him). And then, as if silently cued by God above or suddenly possessed by an invisible spirit, Dahl turns to the camera and begins reciting the story at a breathless clip.

Somehow, production designer Adam Stockhausen’s diorama-like sets manage to keep up with Dahl’s words. As the author speed-talks at us about a self-inflating London aristocrat named Henry Sugar (what are the odds?), Dahl’s cabin lifts into the sky on a pair of wires to reveal a fabulous series of movable backdrops and modular props that are wheeled in and out of frame at will.

And so the stage is set for the most visually inventive film that Anderson has made thus far, one whose in-your-face theatricality and manic bricolage of nested subplots are so aggressive that even the recent “Asteroid City” — with its movie about a television program about a play within a play “about infinity and I don’t know what else” construction — feels measured by comparison. So while “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” may be, in some respects, the most literal Dahl adaptation you could possibly imagine, the true author of this project is never in doubt.

And why shouldn’t it be? Far from a disposable exercise that only exists because Anderson was offered a boatload of streaming money, this short — and, presumably also the other three pieces that comprise the larger project — is yet another vital chapter in the filmmaker’s career-long obsession with self-understanding in a senseless world. Its presentation is something we’ve never really seen before, either from Anderson or anyone else, but its ethos couldn’t be more familiar to anyone who’s followed his work.

Like “Asteroid City” before it, “Henry Sugar” overtly explores how storytelling can serve as an avenue towards life’s greatest truths, but where that movie was preoccupied with finding solace in the unknown, this one hinges on using artifice to see through all the bullshit. If Dahl’s story was a rebuttal to all the critics who accused him of being too mean, Anderson’s film is an unambiguous middle finger to anyone who thinks his stuff is all style and no substance.

But the style here sure is outrageous, as the hermetic nature of Dahl’s plot gives Anderson the chance to make something that has no grounding in reality. There isn’t any “now” in “Henry Sugar,” nor a single moment when its story exists apart from its telling. All five of the film’s actors play multiple roles, and even the most dramatic changes of scenery are seamlessly accomplished with a simple move of Robert Yeoman’s camera, which dollies right just in time for Dahl to pass the narrator’s baton to Mr. Sugar himself (Anderson newcomer Benedict Cumberbatch, a natural addition to the filmmaker’s troupe).

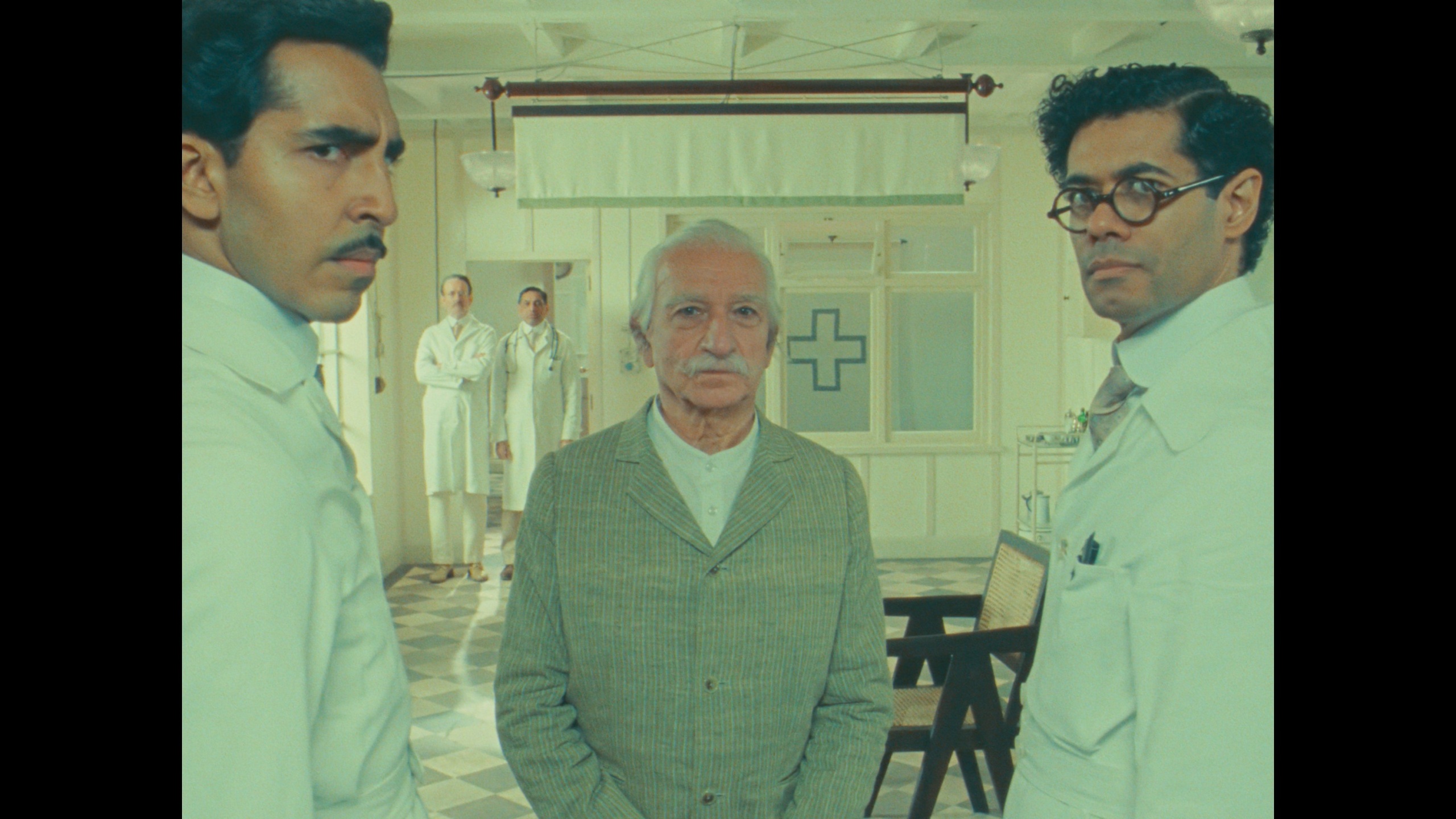

We find the inveterate playboy idling away in a lavish country estate, and thinking — as people who confuse their riches for self-worth often do — of how to make himself richer. That’s when he stumbles upon a curious doctor’s report about an Indian circus performer named Imhrat Khan, played by a deadpan Ben Kingsley, who could see the world around him without the use of his eyes. And so, in a pattern well familiar to fans of “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” the second layer of Anderson’s framing device gives way to a third (and later to a fourth) as Imhrat steps in to relate his tale. Enter: Richard Ayoade and Dev Patel as two disbelieving British doctors, which is every bit as delightful as it sounds.

With all the players introduced, “Henry Sugar” is free to embrace the full extent of its theatricality, and Anderson in turn invited to go totally off the leash. We’re talking dioramas, rear-projection, an on-screen stagehand, and a fetishistic degree of pleasure taken in all of the literary quirks that film adaptations exist to avoid.

Dahl’s text is elided somewhat, but the parts that remain are read word-for-word, down to each individual “he said” (imagine listening to the best-performed audio book you’ve ever heard played at 4x speed). When Ayoade tells us that his character’s “whole face was rigid with shocked disbelief,” he then turns to flash the camera what that expression might look like. That kind of breakneck cleverness proves typical of a short that takes every sentence as a personal challenge to do something fun with it.

It also proves typical of a short that constantly recites information in the driest way possible, only to then immediately add a layer of fourth-wall-breaking fakery on top of it that brings it to life — an approach that becomes all the more brilliant as Henry Sugar’s fascination with artifice begins leading him towards deeper truths. Khan’s powers are so incredible that Henry thinks they must be a trick, but further investigation suggests that the real falsehoods lie in his own conception of reality. No wonder Anderson has now adapted Dahl twice.

I’ll leave you with a telling passage about Khan’s circus act:

“The audience loves it. They applaud long and loud. But not one single person believes it to be genuine. Everyone thinks it is just another clever trick. And the fact that I am a conjurer makes them think more than ever that I am faking. Conjurers are men who trick you. They trick you with cleverness. And so no one believes me. Even the doctors who blindfold me in the most expert way refuse to believe that anyone can see with out his eyes. They forget there may be other ways of sending the image to the brain.”

They may forget, but Anderson never has.

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” premiered at the 2023 Venice Film Festival. Netflix will release it in select theaters on Wednesday, September 20, and it will be available to stream on Netflix starting Wednesday, September 27.