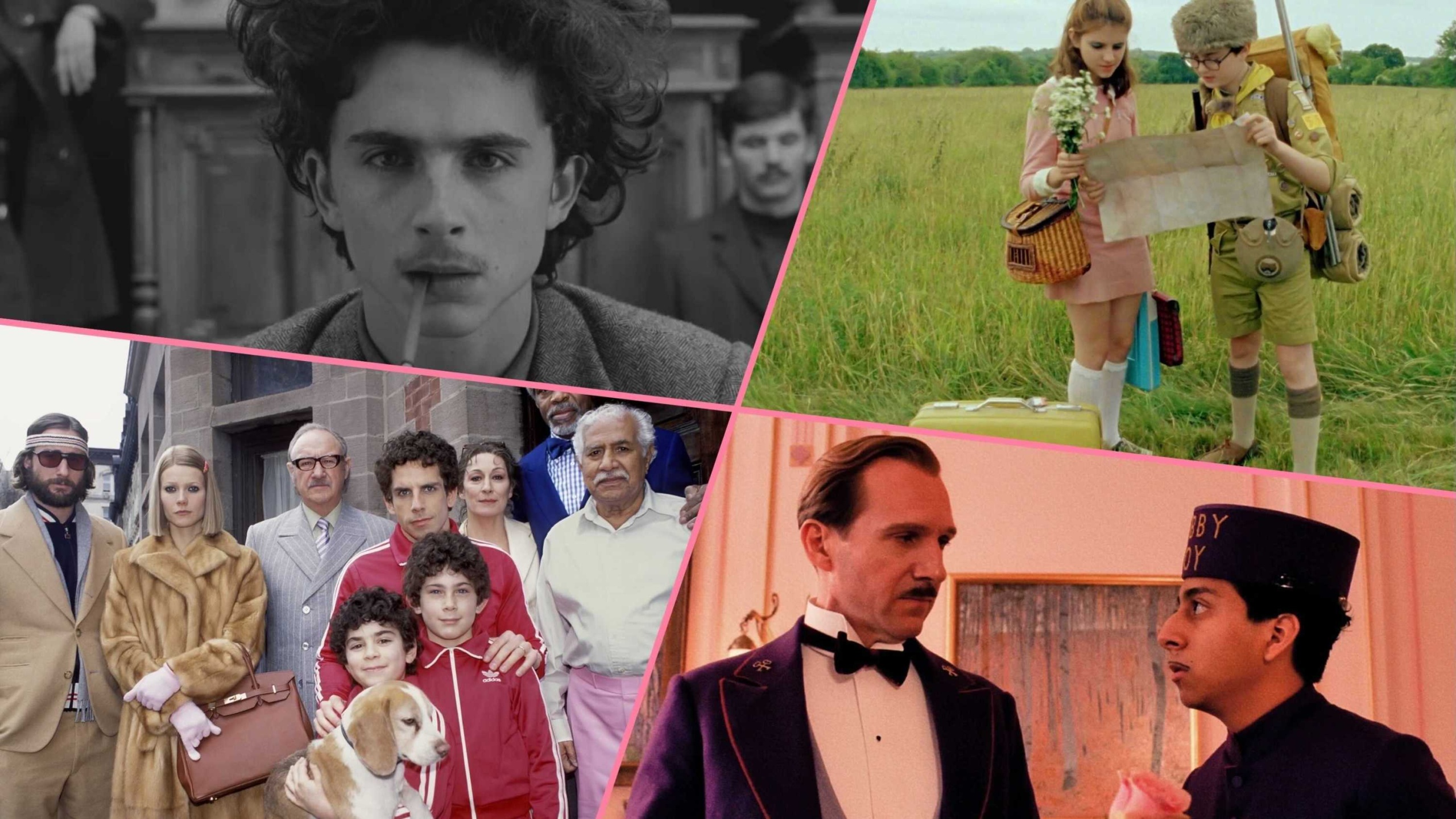

Let’s get this out of the way right from the top: Wes Anderson has never made a bad movie, and — in all likelihood — he probably never will. He’s too particular, too immaculate, too in command of his craft. Of course, the fact that he has always been so sure of himself only makes it more tempting to chart the progress of his career and to measure his films against each other. Or maybe it’s just fun because there are still only 11 of them, and everyone seems to have their own favorite. Who could say?

Anderson is the rarest of rarities, an arthouse filmmaker who not only finds ways to consistently make ambitious original projects, but also maintains genuine influence on what remains of mainstream pop culture. (None of the other esteemed directors who competed for the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival were the subjects of viral TikTok trends.) But the instantly-recognizable aesthetic that propelled Anderson to filmmaking superstardom often prompts his critics to look at his work through an oversimplified lens.

Many of Anderson’s films contain similar stylistic flourishes — like twee interior design with perfect color palettes, inserts of hand-written notes, and the presence of Jason Schwartzman, to name a few. But the visual similarities mask the fact that he has covered an insanely wide range of narrative ground in his 25 years of filmmaking. From dry comedies and whimsical animated features to painfully mature dramas about the nuances of grief, Anderson’s filmography is anything but monolithic. We all know what a Wes Anderson movie looks like, but the differences between his films and the substance of his artistry are complex subjects that merit rigorous debate.

With “Asteroid City” opening in select theaters this weekend (and his Roald Dahl adaptation “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” hitting Netflix later this year), it’s a perfect time to reevaluate Anderson’s catalogue. Here are all of Wes Anderson’s feature films, ranked from “worst” to best.

[Editor’s note: This story was published on May 1, 2017 and has been updated multiple times since.]

11. “The Darjeeling Limited” (2007)

Almost as indebted to Satyajit Ray and Jean Renoir as “The Grand Budapest Hotel” is to the writings of Stefan Zweig, “The Darjeeling Limited” never pretends that it isn’t the work of a white guy from Texas who was raised on the “exoticism” of movies like “Charulata” and “The River.” On the contrary, Wes Anderson’s uneven fifth film confronts that naïveté head-on, telling a story about three grieving brothers who travel to India with the half-assed hope that they can bottle up some of the country’s spiritualism and take it home as a souvenir.

Riding the eponymous train through the countryside and looking out the window like everything they see is a backdrop for their self-obsessive bullshit, Anderson’s most noxious cast of characters learns the hard way that you can’t be a tourist in your own family. Modernist to the extreme and a bit stilted as a result, “The Darjeeling Limited” doesn’t quite match the sum of its parts, but — from Bill Murray’s opening dash to Amara Karan’s unforgettable performance — the parts are pretty great. —DE

10. “Bottle Rocket” (1996)

Wes Anderson arrived fully formed (or close to it), and so much of his cinematic ethos can be distilled from the very first shot of his very first film, the camera crashing in on Luke Wilson’s young face with the confidence of a master and the exuberance of an eternal kid. And it’s really that energy that makes “Bottle Rocket” such a perfect indication of what was to come.

Yes, the film is full of Anderson’s future signatures — whip-pans, insert shots of handwritten lists, overly elaborate plans, the hierarchy of accessories that are assigned for infiltration missions (and used as measuring sticks for love) — but the director’s debut points the way forward because it’s so high on its own existence, its characters as committed to the bubbles they create for themselves as we are to watching them burst.

Anderson’s most naturalistic film by a long shot (there’s something so intolerably casual about those gray skies), this puckish caper movie sputters out at least three different times before James Caan even shows up to spark the third act, but “Bottle Rocket” is colorful even when it isn’t sparkling. Would Wes Anderson have even been possible without Owen Wilson there to translate him for us? His Dignan, dreamy and deranged, set the mold for at least seven movies to come, playing the guy in an electrified defensive coil of some kind, always trying to disguise themselves and doing such a poor job of it that you can’t help but laugh at their transparency (“What are you putting that tape on your nose for?” Bob Mapplethorpe asks. “Exactly,” Dignan replies). Thank God someone was able to see through the film’s disastrous box office performance and recognize that this was the start of something great. —DE

9. “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou” (2004)

“Oh, shit! Swamp leeches. Everybody, check for swamp leeches, and pull them off… Nobody else got hit? I’m the only one? What’s the deal?”

It’s amazing, just when he was on the verge of becoming a household name, Wes Anderson made a dry nautical epic about Jacques Cousteau being a shitty father. I mean, I’d appreciate this movie being made under any circumstances, but “The Life Aquatic” is the only Wes Anderson film that feels as though it exists for the simple reason that someone was willing to fund it.

As exhaustingly dense as “The Royal Tenenbaums,” as spirited as “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” and as anarchic as “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” this expansive adventure is even better than the Adidas sneakers it inspired. Yeah, it sits uncomfortably in the middle of Anderson’s career and sometimes play like a watered down version of his previous work, but it also features Bill Murray as a vengeful shark hunter, Seu Jorge covering David Bowie, Cate Blanchett radiating right off the screen, Willem Dafoe as an over-sensitive German sailor, and Bud Cort giving us the closer that “Harold and Maude” never did. —DE

8. “The French Dispatch” (2021)

If the two decades that brought us “Rushmore,” “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” and “Moonrise Kingdom,” felt like a passionate love affair between cinephiles and Wes Anderson, the release of “The French Dispatch” is more akin to settling into a comfortable relationship. The excitement inevitably fades when you pretty much know what you’re going to get, but that does not negate the fact that Anderson is one of the most technically proficient filmmakers working today. As his aesthetic becomes more recognizable, if that’s even still possible, the (often unfair) question of what Wes Anderson is offering beyond unique interior design choices and snappy dialogue will weigh on him more with each subsequent film.

“The French Dispatch” succeeds in part because it does not particularly try to answer that question, instead offering a light ensemble piece that goes down relatively easily and gives Anderson plenty of opportunities to work with new actors and show off the cinematic bells and whistles his devotees have come to expect. The thinly veiled tribute to The New Yorker does an excellent job of weaving multiple stories together without boring audiences, even if that means sacrificing the narrative heft of some of Anderson’s earlier films. While this was probably Anderson’s first opportunity to cast Timothée Chalamet since the young actor broke through in 2017, the pairing still felt long overdue. As did the film’s decision to partially shoot in black and white, which gave Anderson a new color palette that produced some stunning shots. Anderson’s technical precision has never been better — even if the film looks less flashy than some of his earlier work, there is no doubt that he is at the top of his game as a visual filmmaker. “The French Dispatch” did not represent a massive step forward in Anderson’s filmography, but it was not a step backward, either. —CZ

7. “Isle of Dogs” (2018)

The world is trash, and Wes Anderson is currently enjoying the hottest streak of his career. These things, it turns out, are not unrelated. The worse things get, the more fantastical Anderson’s films become; the more fantastical Anderson’s films become, the better their style articulates his underlying sincerity. Disorder fuels his imagination, and the staggeringly well-crafted “Isle of Dogs” is nothing if not Anderson’s most imaginative film to date.

There’s a whiff of inevitability to that. Whether telling a story about a splintered New York dynasty or one about a faded European hotel where it used to be possible to find some faint glimmers of civilization in this barbaric slaughterhouse known as humanity, Anderson has always been attuned to the beauty of magical idylls, to the violence of losing them, and (most of all) to the fumblingly tragicomic process of building something better from the rubble. So at a time when global warming and gun violence have become inescapable — a time when fascism and xenophobia are no longer abstract threats so much as Republican campaign promises — it’s no wonder that America’s fussiest auteur is operating near the peak of his powers.

“Isle of Dogs” is the work of an artist who’s howling into the same wind that’s currently blowing in all of our faces. Blending Akira Kurosawa and Hayao Miyazaki into a darkly comic fable about a boy, his dog, and a world that’s on the brink of running out of biscuits, this is a movie that literally asks: “Who are we, and who do we want to be?” And since it’s a Wes Anderson movie, those questions are posed straight into the camera. It’s funny, it’s grim, and it’s probably the most pet-able bit of dystopian fiction we’ve ever seen. —DE

6. “Asteroid City” (2023)

If all of Anderson’s movies are sustained by the tension between order and chaos, uncertainty and doubt, “Asteroid City” is the first that takes that tension as its subject, often expressing it through the friction created by rubbing together its various levels of non-reality. Some might see that as self-amused navel-gazing, but the unexpected moment towards the end when Anderson finds a certain equilibrium between those contradictory forces — with a major assist from a movie star whose name you suddenly remember seeing in the credits some 100 minutes earlier — is so crushingly beautiful and well-earned that the artifice surrounding it simply falls away.

Read IndieWire’s complete review of “Asteroid City” by David Ehrlich.

5. “Rushmore” (1998)

For such a singular artist and aesthete, Wes Anderson has always been comfortable with wearing his influences on his sleeve, rightly confident that he can celebrate his touchstones without resigning to them. For proof, just look at the way his characters worship each other in order to find themselves — from Ned Plimpton’s childhood obsession with Steve Zissou, to the mild awe that Gustave H. inspires from his new lobby boy, Anderson understands that self-discovery is the last stage of a failed attempt to become someone else. Maybe that’s why “Rushmore” represented such a breakthrough for him, because this coming-of-age story about a super precocious kid (and the grown man who goads along their mutually assured destruction) is so giddy about the things that made it possible.

Running on the fumes of the French New Wave and drafting behind American touchstones like Mike Nichols and Albert Brooks, Anderson’s second feature is like an artistic manifesto that never declines to cite its sources. And, not for nothing, it gave the world Jason Schwartzman, reinvigorated Bill Murray, and — most importantly — made it possible for generations of viewers to say “Wait wait, go back… was that Rory Gilmore!?” “Rushmore” is a film as self-possessed as its hero (and many times cooler), and that makes it a favorite for many, but it lacks the sentimental spark that galvanizes Anderson’s more mature work. —DE

4. “The Royal Tenenbaums” (2001)

The Wes Anderson movie that people think of when they think of Wes Anderson movies, “The Royal Tenenbaums” is a story about failure that’s told by someone who’s afraid of his own ambition (or, more precisely, afraid of his unwillingness to tame it). Unfolding like “Fanny and Alexander” as remade by a very drunk Whit Stillman, “The Royal Tenenbaums” is responsible for so many of the worst quirks of recent indie cinema, but it falls victim to exactly none of them. It’s a film where the characters are cobbled together from affects, but all manage to feel human. It’s a film that feels overstuffed to the gills, but one whose every moment is iconic — gather enough twentysomethings together, and their Tenenbaums tattoos could serve as storyboards for the entire script. It’s a film that leaves me a little cold every time I watch it, but always feels worth watching again. —DE

3. “Fantastic Mr. Fox” (2009)

Wes Anderson’s career can be cut into two distinctly different parts: Before “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” and after “Fantastic Mr. Fox.” Stung by accusations of self-parody, Anderson could have eased off the gas after “The Darjeeling Limited” divided critics and inspired all sorts of talk about how the filmmaker had grown subservient to his own style. But rather admit that the tail was wagging the dog, Anderson snipped the damn thing off and let his next hero wear it as a necktie.

He introduced himself to audiences as an aesthete, and every one of the films he made after “Bottle Rocket” had a little less breathable air than the last, but that was fine by Anderson. If anything, he wanted more control, he wanted to play God, he wanted to make something so airless that his characters wouldn’t even need to have lungs. And so he ventured into the painstaking world of stop-motion, working in a medium where literally nothing made its way on screen unless he thought to put it there. It turns out that yeah, everything else was just getting in the way.

Flattering Roald Dahl’s (lovely) source material into a gloriously wry domestic comedy about compromise, belonging, and accepting one’s lot in life (be it in below ground or above), “Fantastic Mr. Fox” is more than just one of the most quotable films this side of “Casablanca,” it’s also an immaculate portrait of flawed “people” doing the best they can for themselves and each other. —DE

2. “Moonrise Kingdom” (2012)

A pre-pubescent “Badlands” that’s told with the endearingly pathetic quality of an elementary school play, “Moonrise Kingdom” is the rare American film that’s about children, but not necessarily for children (a schism that studios can’t seem to wrap their heads around, but one that artists like Robert Bresson, Ingmar Bergman, and Hayao Miyazaki have always been able to reconcile with ease). The movie begins with the most perfect premise that Wes Anderson has ever devised for himself: Two kids get together and try to run away from home, only to be stymied by the fact that they live on an island. If you squint, that pretty much sums up every Wes Anderson movie.

But “Moonrise Kingdom” isn’t a story about being stuck, it’s a story about how the things we can’t escape are often the things that love us the most, about how the greatest myths are the ones we create for ourselves, about how everything is better when narrated by Bob Balaban. It’s like a mousetrap, it’s written with a whimsical Dickensian flair, and it’s filled with lines so evocative that merely reading them can bring the whole film back to life (“I love you, but you don’t know what you’re talking about”). Anderson has made a lifetime’s worth of family sagas, but none of his other movies so pointedly capture what it feels like to have a home. —DE

1. “The Grand Budapest Hotel” (2014)

There will always be some debate as to whether or not “The Grand Budapest Hotel” is the best Wes Anderson movie, but there may be no denying that it’s the most Wes Anderson movie. The latest work from an artist who seems to become himself a little bit more with every film, this flawless, four-tiered confection is like a wedding cake filled with arsenic, a nostalgic comedy that functions like a requiem for itself.

Anderson’s stories are about boys, men, or male foxes who seek to live in snow globes of their own design, ensconcing themselves in the empire of their own imaginations. Some of his films (e.g. “Moonrise Kingdom”) are about creating those magical spaces, but most of his stories are about the heartache of losing them, about the tragicomic process of building something new on top of the rubble. With “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” Anderson directly confronts the hermetic fantasy of his films, reaching into the not-too-distant past and exhuming the spirit of Stefan Zweig in order to mourn the world we lost, the civility that we’ve forgotten, and the beauty of creating beautiful things even when we know that the world will never let them survive.

The film is so beautifully realized that Ralph Fiennes’ career-best performance almost feels like the cherry on top. Also: Willem Dafoe playing the best henchman who Bond never killed, and Tilda Swinton as a sexually active octogenarian. And Saoirse Ronan’s Mexico-shaped birthmark. Oh, and also the best line that Anderson has ever written, shrugged off like an afterthought in the first act: “You see, there are still faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity. Indeed, that’s what we provide in our own modest, humble, insignificant… oh, fuck it.” —DE