For the most part, the opening ceremony of the 76th Cannes Film Festival was a tightly scripted affair. The show, which was broadcast live across the country from the Lumiere theater on the public television channel France 2, included an honorary Palme d’Or for Michael Douglas, who stumbled through a speech from a teleprompter at the back of the room and bungled a few words of gratitude in French. Catherine Deneuve came out and read a poem about Ukraine. Host Chiara Mastroianni offered the usual platitudes. “The cinema has never abandoned us,” she said. “We, in turn, must commit ourselves to it for the next 10 days.”

Yet when jury president and Swedish director Ruben Östlund took the stage after a generous montage of his acclaimed satiric work, he appeared to improvise a speech about the value of watching movies together. “Back in the day, we were gathering in front of the TV,” he said, “but the only content that we watch together in Sweden now in front of the TV is the Eurovision Song Contest.”

The audience laughed along. “All other content we are scrolling on small individual screens alone in our rooms,” Östlund said. “My point is that when we are watching things like this alone, we are processing images in a completely different way. It doesn’t demand us to think. The algorithm that is curating the content basically only wants us to keep on watching.” By watching movies with a crowd, he added, “just the fact that someone is sitting next to you and might turn to ask you what you thought means you have to take a standpoint. … I think it’s important that we are in one of those rooms where we are processing the content we are watching.”

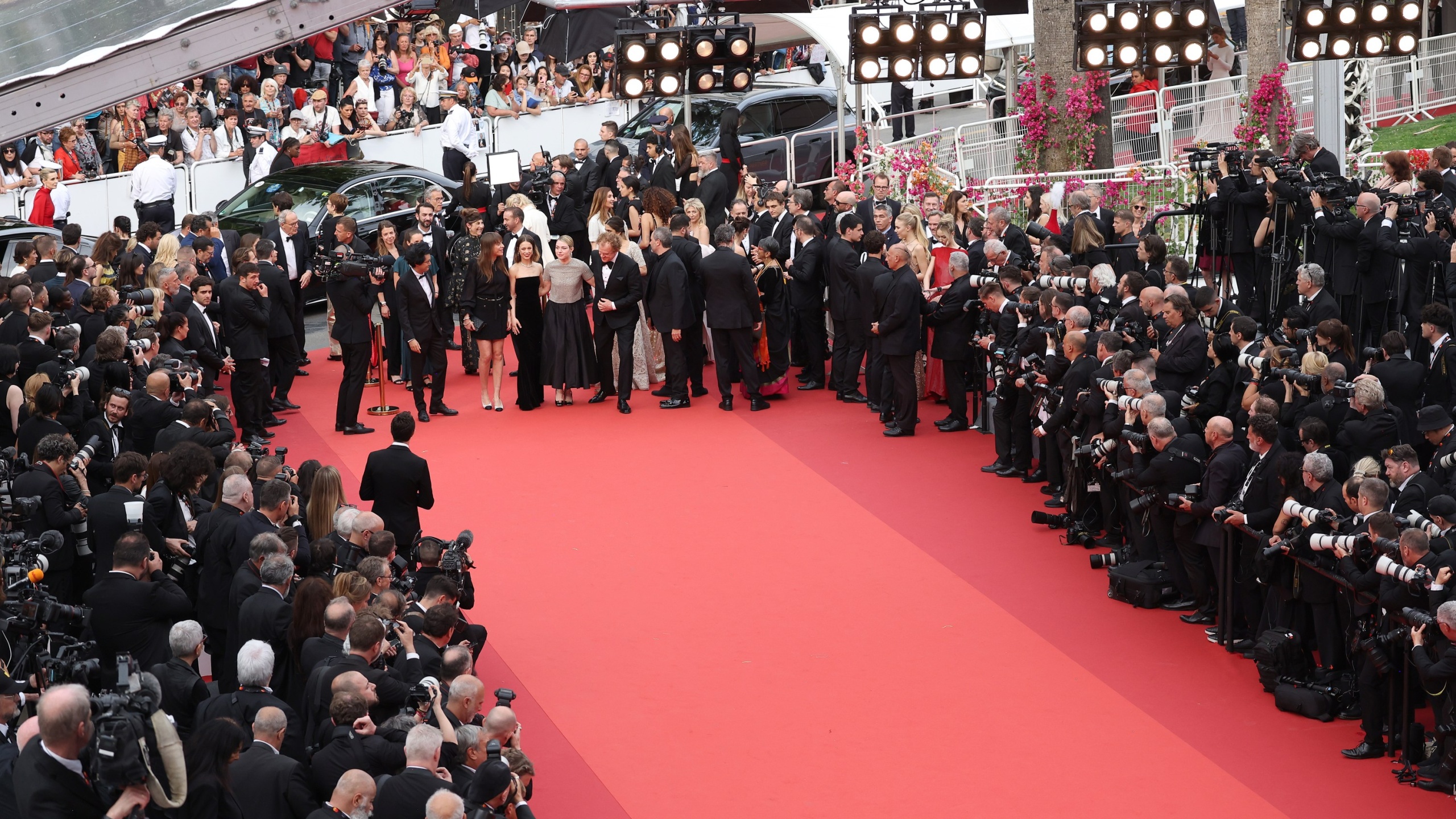

It was an intriguing observation to kick off a festival entrenched in its traditions, from the European filmmaking that dominates the program to the formalities of the screenings themselves. Watching movies at Cannes isn’t just about whatever projects onscreen; the environment becomes part of the show.

The opening ceremony was followed by “Jeanne du Barry,” French director Maiwenn’s engaging, airy portrait of Louis XV’s favorite lover, played with an air of playful rebellion by the provocative filmmaker herself. The role of the king falls to Johnny Depp, a controversial figure in the U.S. but one who was welcomed with plenty of cheers when he arrived at the theater. As the lights went down, one tux-clad audience member couldn’t help but shout, “We love you, Johnny!”

The movie won’t do much to alter Depp’s complicated reputation in the wake of his court case with Amber Heard, but as a fairly minimal presence in the movie, its potential doesn’t solely rest on his appeal. While U.S. buyers at the screening ranging from Sony Pictures Classics to MUBI seemed intrigued, Netflix is also a player in the conversation since it helped finance the project. However, the movie recalls another era of arthouse cinema: “Jeanne du Barry” drifts through the romance at its center with the old-school likability of a commercial French movie that would have played like gangbusters at the Lincoln Plaza a few decades ago.

Now, its prospect in that kind of market were less clear. SPC co-president Michael Barker told IndieWire after the screening that he liked the movie, but said “I haven’t had a chance to think about it yet” when asked if he might consider taking it on.

Time will tell, but the main Cannes crowd was ready to move on. Depp skipped the official festival dinner in favor of the film’s own afterparty, but over 600 people — largely press and industry — crammed into a dining hall at the Carlton Hotel for the opening dinner after the movie. Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences CEO Bill Kramer sat with Berlinale chief Carlo Chatrian as they discussed the future of exhibition in the streaming era.

While the Academy is expected to reassess its theatrical requirements for Best Picture in the coming months, the Cannes policy about theatrical releases remains unequivocal: Films in competition for the Palme d’Or must receive a theatrical release in France. Chatrian said that Berlin’s policy was more fluid, merely requiring that films at the festival must receive a release in some fashion around the world — not necessarily in Germany. “I think streaming and theatrical will become more and more distinct,” he said.

The vapor from Deneuve’s e-cigarette wafted past them from a few seats down. She sat with her ex-husband, former Cannes president Pierre Lescure, who stepped down from his role last year with the election of new festival leader Iris Knobloch, the first woman to hold the role. Knobloch, a former WarnerMedia executive, is known more for her business acumen than cinephile bonafides.

Addressing the Cannes crowd for the first time, Knobloch singled out Östlund. “You have that incredible talent to immortalize everyday events and the moments that turn sour,” she said. “Standing up here I can’t stop thinking of Ruben’s film ‘The Square.’” That Palme d’Or-winning takedown of the fine art world includes a memorable performance art sequence in which affluent dinner guests are thrust into the center of disturbing, confrontational performance art as the celebratory air gives way to fear.

At the Cannes dinner, no such chaos unfurled, though there was a lingering uncertainty about how the next two weeks would go. Seated across from Deneuve was John C. Reilly — the head of the Un Certain Regard jury — alongside his wife and producing partner Alison Dickey, who remarked that American movies produced in the low-seven-figure range were impossible to get made now. Nearby, sales agent Vincent Maraval (whose longtime Wild Bunch factory has been rebranded Goodfellas this year) peered around the room, hunting for buyers. Jury member Damian Szifrón, whose “Wild Tales” was a Cannes hit back in 2014, said he was plotting a sequel. His fellow juror Paul Dano looked pleased to be playing a different kind of role for the next 10 days. “I don’t think I’ve ever watched three movies a day like this before,” he said. “I’ve got to get some sleep.”