Anyone who has watched the Criterion Channel knows that writer-director Ari Aster is a devoted cinephile with broad taste and a deep understanding of how and why movies work. For his latest and most ambitious film, “Beau Is Afraid,” Aster told IndieWire’s Filmmaker Toolkit podcast that he tried to leave specific tributes to other movies behind, at least consciously. “I would say that a lot of the influences were unconscious while I was writing it,” he said. “I became aware of them while we were shooting, or even in post.” Aster and his regular cinematographer, Pawel Pogorzelski, talked more about literary references than cinematic ones, but there’s no denying that several of the classics that Aster has “metabolized,” as he put it, found their way into the visual and aural DNA of “Beau Is Afraid.” Here are three key films that influeced Aster and Pogorzelski’s approach.

“Playtime”

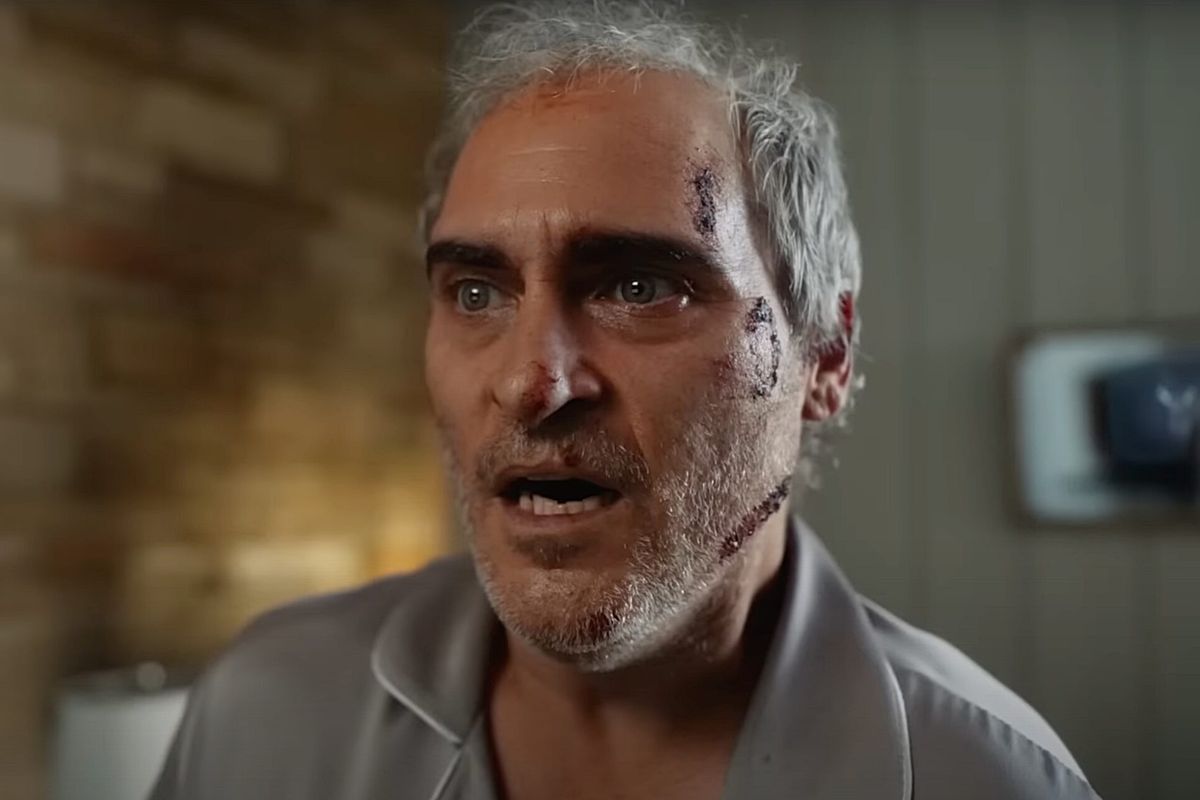

Jacques Tati’s 1967 comic masterpiece is a clear inspiration for “Beau Is Afraid,” both visually and tonally. “I definitely looked at the way that he created humor through set design, blocking, and camerawork,” Pogorzelski told IndieWire. Though “Playtime” is more playful and less anxiety-inducing than “Beau Is Afraid,” it sets up a similarly hostile environment for its protagonist. Tati’s Mr. Hulot is surrounded by modernist buildings made up of hard lines and stripped-down decor, with reflections and frames within frames that are extremely complex yet clear and accessible to the viewer. The first act of “Beau Is Afraid,” in which the title character (Joaquin Phoenix) is plagued by terrifying forces in and around his apartment, creates a similarly clean yet dense network of windows, doorways, and off-screen spaces in which sounds that utilize all the surround channels (just as Tati did in his 70mm epic) overwhelm our protagonist. Aster’s skillful juxtaposition of sound and image, in which sound effects are often missing, exaggerated, or moving through space at an abnormal speed, yields just as many laughs as Tati’s sophisticated construction, even if there’s a more frightening undercurrent.

“Rear Window“

Throughout “Beau Is Afraid,” there is a sense of Beau being watched and listened to by forces that probably don’t have his best interests in mind, which makes Alfred Hitchcock’s 1954 classic of voyeurism a logical reference point. According to Pogorzelski, it was Hitchcock’s palette that most influenced “Beau.” “We were looking at the color rendition and the kind of atmosphere that created,” he said. “Beau Is Afraid” doesn’t so much imitate Hitchcock’s palette — the closest it comes to replicating the warm browns and yellows of “Rear Window” is in the theatrical forest sequence around halfway through the film — as it adopts his technique of using color to elicit emotional responses in the audience. Each movement of the film has its own palette, with the opening sequence immediately putting the audience on edge with its abrasive mustard tones.

Perhaps the most effective use of color comes in the sequence that follows, when Beau finds himself in the home of a superficially kind but inexplicably menacing family; the aggressive pastels of the bedroom in which he “recuperates” make this safe haven nearly as horrifying as the urban hellscape from which Beau has just escaped. In addition to the color, Aster builds on Hitchcock’s cinematic experiments with point of view; we are largely limited to what Beau sees and experiences, and, as in “Rear Window,” the rare occurrences where the audience becomes privy to information not available to the hero are pivotal toward the film’s building of suspense.

“Defending Your Life“

When Aster conceived the final scene of “Beau Is Afraid” — in which Beau is forced to defend himself and his choices in an arena filled with strangers — he had in mind Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1946 fantasy film “Stairway to Heaven” (aka “A Matter of Life and Death”). Once he looked at the scene during post-production, however, he realized another favorite film had found its way into the mix. “It occurred to me that the scene was nodding to ‘Defending Your Life,’ without my awareness,” he said. “That’s a film that’s very important to me, and I love it so much.” Brooks’ 1991 masterpiece portrays an afterlife in which the recently deceased sit in courtrooms (which, in a typically sly Brooksian metaphor, visually resemble the studio executives’ screening rooms where he had presumably spent his career being judged) and endure an assessment of their lives by attorneys and judges; in Aster’s film, the process is both more disturbing and more personal, with Beau’s own mother on the prosecution’s team. While the parallels between the final scene and “Defending Your Life” are obvious, the relationship between the two films runs deeper than that finale; like “Defending Your Life,” “Beau Is Afraid” is ultimately a philosophical meditation on how our lives are defined by fear and an inquiry into whether or not we can conquer fear or grow from it. Brooks’ film is ultimately life-affirming and romantic where Aster’s is brutally pessimistic, but the issues and the seriousness with which the filmmakers address them are consistent.