On December 6, the 2023 IndieWire Honors ceremony will celebrate 11 filmmakers, creators, and actors for their achievements in creative independence. We’re showcasing their work with new interviews leading up to the Los Angeles event.

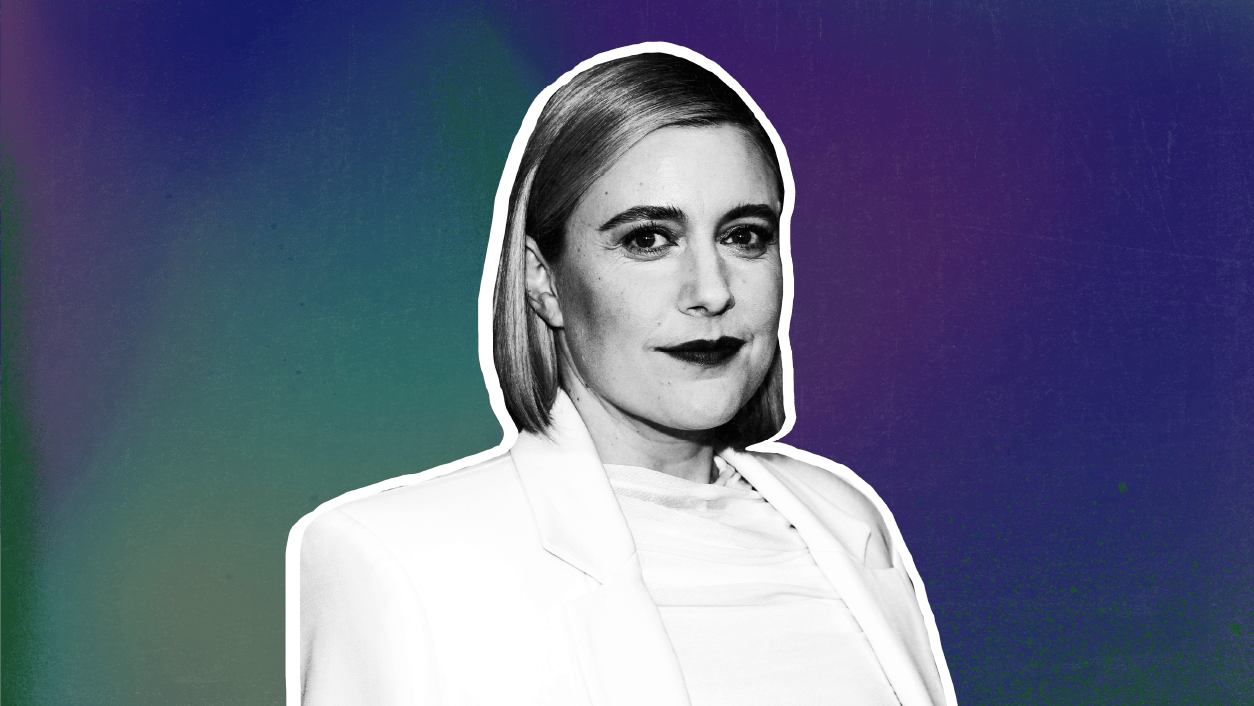

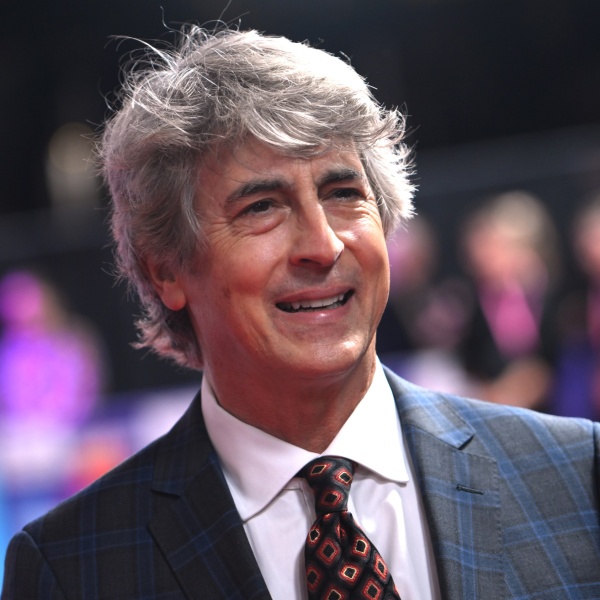

When filmmaker Greta Gerwig hit the promotional trail for her summer smash hit movie “Barbie,” which Warner Bros. sold as a mainstream pink confection but which critics recognized as a brainy Trojan Horse packed with clever ideas about gender and the power of a child’s imagination, she did so without her writing and life partner Noah Baumbach, who was honoring the WGA strike at the time.

Baumbach watched from the sidelines as their shared creation, which they thought was too crazy to ever get made, wowed not only audiences across the world, but outgrossed every movie in sight, bringing in $1.45 billion worldwide. While Gerwig has directed such Oscar-nominated prestige hits as “Lady Bird” ($80 million worldwide) and “Little Women” ($218 million worldwide), no one was prepared for “Barbie” to succeed at this blockbuster level.

“Barbie” started out as a meeting between Margot Robbie, Mattel’s choice for producer and title star, and Gerwig, who had long wanted to work with the Australian actress. At that point, Baumbach was not on board. “Greta mentioned, we’re gonna write this ‘Barbie’ movie,” said Baumbach during a recent interview with IndieWire. And I said, ‘That’s a terrible idea.’ Like, we were clearly never going to do it.”

It was Gerwig who took the deep dive into Barbie research, not Baumbach. And then she ran with the ball and struck a deal for him to write the movie with her. “I just had a feeling that it would be extremely fun and funny,” Gerwig told IndieWire. “We hadn’t written together in a long time. Even when we’re not credited on each other’s stuff, we’re always looking at everything and giving feedback and talking all the time. But we hadn’t actually sat down and written something together. And in my heart, I felt, ‘It’s so fun to write together.’ I thought there would be a comedic energy I would be able to access.”

During the pandemic, the two were holed up together in a house on Long Island. And when Gerwig showed Baumbach her first scene, where Barbie comes out of her dream house and finds a sick woman from the real world in her backyard, Baumbach suddenly saw the light. “I understand this ‘Barbie’ movie,” he said. “That element embracing mortality and sadness and sickness and everything that it means to be human, is the whole movie. That scene explained what the movie could be to me. Then I was in.”

“What is the thing that Barbie has no answer for? It’s decay and illness and dying,” said Gerwig, who was struck by the poignant story of Ruth Handler, who invented the first doll with breasts and later contracted breast cancer and invented prosthetic bras for mastectomy patients. (She put her in the movie.) “What does Barbie say about bodies falling apart? It felt connected in some deep way.”

Gerwig and Baumbach took a lot of walks during that time. He would get ideas in yoga. When they got home, they would each write scenes. “There’s a moment when you send the other one a scene,” said Gerwig. “Nothing is more fun than making Noah laugh. He’d write a scene and I’d write a scene and then we’d bring it to each other and rewrite each other’s scenes.”

For his part, Baumbach peeked around corners and listened for Gerwig. “You hover, but try to leave a little bit of time,” he said.

“There was a confluence of circumstances which made us able go for broke,” said Gerwig. “Because we thought, ‘Well, this will never get made. So if it will never get made, let’s make the greatest, craziest thing that will never get made.’ There was a private wish to conjure back the world. And let’s make something that people would want to see together. But the more immediate reality was, ‘They’re not going to let us do it.’”

They were writing with unfettered freedom because neither writer delivers outlines or treatments along the way. “It can let the air out of an idea,” said Gerwig. “It needs to grow. Part of the pleasure of writing is the not knowing and the discovery.” They also assumed that someone else would have the problem of figuring out how to actually direct the movie, from Barbie Land to intricate musical numbers. So when Robbie and her husband and producing partner Tom Ackerley finally got the first look at the script (the longest draft was 157 pages), they had no idea what to expect.

By then both Gerwig and Baumbach had a sense of what they had wrought. “I don’t think either one of us have been ever more proud to hand something in,” said Gerwig. “This might be the greatest thing we’ll ever write.”

And at that point, and while Baumbach admitted to some envy at handing the directing reins to Gerwig, she knew she wanted to direct, assuming Mattel and Warner Bros. agreed to make the movie. Gerwig and Baumbach dealt with many notes (taking the interlocking script apart was a challenge) and acted out much of the script over many Zoom meetings. “It was so obvious to us,” said Gerwig, “but then we realize we have to bring everyone else into what was obvious.”

“Sometimes people said, ‘Well, there are too many movie references,” said Baumbach. “And our feeling was no, because it’s about culture. Movies are one of the things that kids take and put into their play, and they use these tropes. We were using tropes of things, so that we could then come up with cracked ways of using them.”

Mattel and Warners finally got on board, Gerwig said, “because they understood inherently, even though it’s spiky, its intentions are not cruel or mean. We love these dolls and these characters, and even when we’re taking the piss out of something, we are not doing it with cruelty. And for whatever reason, they both were extremely open to it.”

Eventually, they got the green light.

The reason “Barbie” is a contender for Original Screenplay is that there was no pre-existing Barbie character or story. “By design, dolls are empty vessels for us to put our own imaginative ideas and thoughts and feelings and fears,” said Baumbach. “And these dolls are being played with by kids. So these dolls have a childlike quality to them. So it starts with the creation story. We were inventing it as we went.”

“But we did know that it was Margot,” said Gerwig. “She was written as Barbie, Margot. We wrote Ken [for] Ryan [Gosling], having not even spoken to him. We didn’t even know him. We just knew as soon as we said it: ‘It’s Ryan, to the point where if he can’t do it, there’s no reason to make it, we were so sure it was him.”

Along with his movie roles, Gerwig was a fan of Gosling’s multiple performances on “Saturday Night Live.” “Like Margot, he is serious actor,” said Gerwig. “It had to be someone who was serious, but also really funny. He doesn’t stand outside of it. He had so many great ‘SNL’ moments, but he’s always playing it from the inside. There’s something about the way he comes at things that are slightly different than you think it’s going to be.”

And then Margot became Stereotypical Barbie. “She says it,” said Gerwig. “‘I’m the Barbie. When someone says, Think of a Barbie, that’s me.’”

This organic writing process yielded rich opportunities for both humor and pathos. “It was the story of finding humanity in a capitalist society, in a world of commerce,” said Baumbach, “so when we make discoveries, like, if Ken is essentially created as an accessory to Barbie, like the car or the dream house, as something to add to the collection for your primary Barbie dolls, what happens when that guy gets to see that there’s another way of doing it? And it’s the way we’re all accustomed to doing it and have been dealing with it and pushing against? That was not something we thought of until we actually arrived there.”

“I remember [Barbie and Ken] getting to Venice Beach,” said Gerwig, “and realizing he’s never seen any man with any amount of power or agency or importance at all. And she’s never been looked at, in the way that feels objectifying. That’s never happened. If you’ve never seen it on either side, it will feel extreme, because you’ve never encountered it before.”

The movie is also about the transition to adulthood. “Because they’re essentially imagined by children,” said Baumbach, “it becomes a child’s idea of all these things. So the movie is also about growing up, because it’s about seeing the world in a childlike way and then having to accept all these adult ideas but wanting to maintain childhood at the same time.”

It took a long time to figure out that it wasn’t a little girl playing with Barbie. It was her mother (America Ferrara). “The age at which you love Barbie is so young,” said Gerwig. “By the time you’re in junior high school, you’re not in love with it. All of a sudden we had this realization: it’s not the daughter, it’s the mom, because you’re always looking back.”

The audacious opener of the movie, a “Barbie” take on the hominid throwing a bone that morphs into a spaceship in “2001,” came to the writers early on. Gerwig was far from confident that it would work and even threw the idea at her therapist, who found it funny. “I don’t want to do it if it’s not beautiful,” said Gerwig. “It’s complicated, one thing in the writing and then in the shooting and then in the editing room that we had to figure out, because there’s a lot of movements and cognitive things you have to do. It wasn’t until I had [cinematographer Rodrigo [Prieto] and [production designer] Sarah Greenwood that I knew how we were going to do it.”

During the editing phase, Warners did want to bring the final running time down during the usual give and take between filmmaker and studio. Gerwig stuck to her guns and kept octogenarian costume designer Ann Roth, sitting on a bench. “You’re looking to take 15 minutes out,” said Gerwig. “Someone says, ‘Well, you could lose Ann Roth and you wouldn’t actually lose momentum.’ But that’s just always what’s happens.”

When they tested the film in February 2023 in New Jersey, Gerwig was about to give birth to their second child. “It was wonderful. It was great,” she said. “Tests are terrifying, always. But there is something exciting when it’s working or you’ve never heard an audience laugh at a joke. And the joke is so stale to you, but they’ve never heard it. And there’s this energy, you could just feel it and it was exciting.”

Since the movie opened on July 21, driving the organic Barbenheimer wave, Gerwig has morphed into a new entity: an A-list Hollywood auteur. She’s still the same person, but the world around her has changed.

“The whole thing always seems to be just that you have the ability to make whatever movie you want to make next,” said Gerwig. “It feels good that I’ll definitely get at least one more at bat.” That includes two “Chronicles of Narnia” films for Netflix. Still, she’s clear: “You’re always clocking how many more swings they’ll give you.” Batter up.