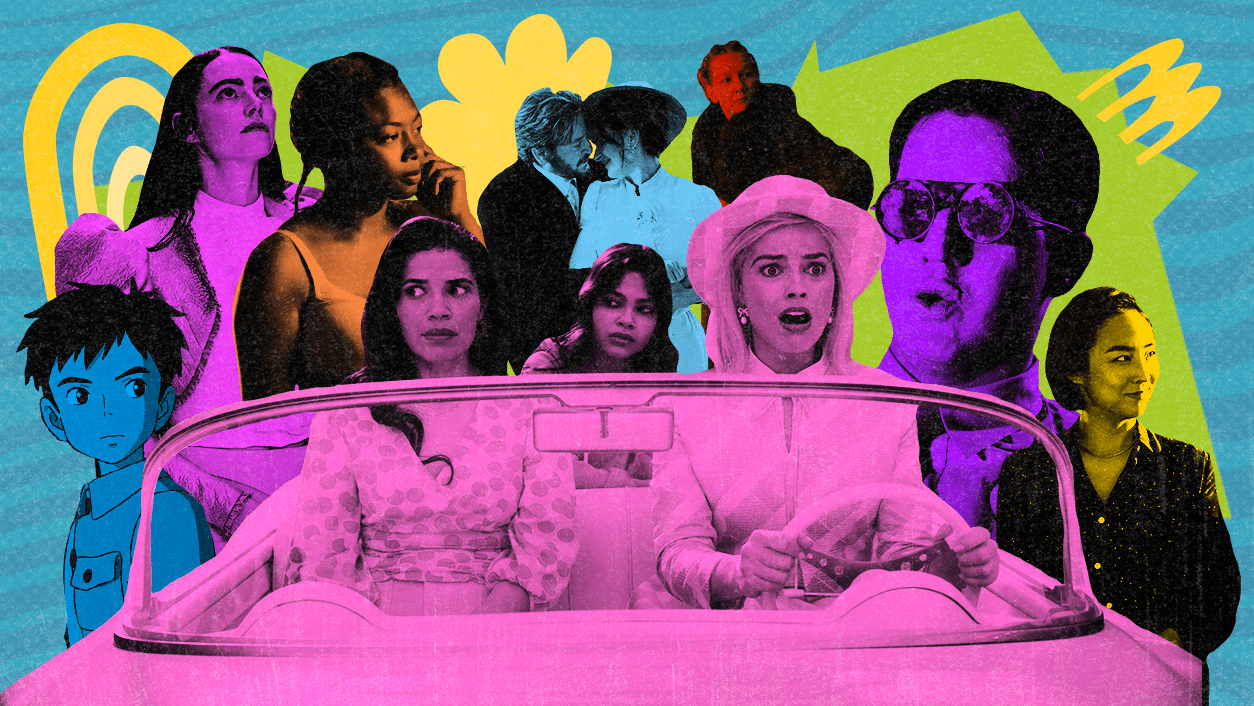

In hindsight, it shouldn’t be surprising that the cinema of 2023 was so preoccupied with the unknown, as the first proper year after the start of the pandemic was always going to find the movie industry plunging into a brave new world.

In hindsight, it shouldn’t be surprising that the cinema of 2023 was so preoccupied with the unknown, as the first proper year after the start of the pandemic was always going to find the movie industry plunging into a brave new world.

Some of the most pressing questions we had at the start of January were answered with resounding force. Would the studios — some of which had fatally diluted their brands with streaming options in a desperate bid to appease the stock market — find that once-reliable franchises had lust their luster? Yes. Would audiences — so eager for a different breed of “event film” that they had already started to redefine the term themselves — actually follow through on the “Barbenheimer” meme that first spread across social media in late 2022? Yes. Would titans like Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, and Wes Anderson make good on the breathless chatter that surrounded their latest projects and predictably inspire some of the most illuminating and demented takes in the history of human opinion along the way? Absolutely.

On the other hand, some of the year’s most pressing questions were harder to see coming in advance, although several of those have also been resolved as well to one degree or another. Would the strikes ever end? Good news! Would documentaries start to feel depressingly irrelevant in the face of a streaming ecosystem that’s made it all but impossible to market anything besides celebrity profiles and concert films? Kind of! (Festival highlights like “Milisuthando” are still awaiting distribution, while other major efforts like “Kokomo City,” “Four Daughters,” and the fittingly titled “A Still Small Voice” have struggled to be heard amid the ever-loudening din of movie discourse). Did David Zaslav learn a valuable lesson from the whole “Batgirl” disaster last summer? Not so much!

And yet it was how the films themselves confronted the unknown that proved most notable about the year in cinema, as several of 2023’s defining movies found their characters and creators looking beyond the limits of their lived experience — or, in the case of “The Zone of Interest” and its timeless moral compartmentalizations, resisting the urge to do so at any cost. This, more than the happy coincidences of their shared release date, is what bonded “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” together; where one film saw heartfelt wonder, the other discovered unholy dread.

That fascination with the unknown is the connective tissue between the mysteries of “Asteroid City” and “The Boy and the Heron,” between the real or imagined multi-verses of “Spider-Man” and “Past Lives,” and between Scorsese’s defeated humility at the end of “The Killers of the Flower Moon” and the barrister’s grinning arrogance throughout the courtroom scenes in “Anatomy of a Fall.” This was a year in which many of the most resonant movies tried to capture the past in hopelessly cracked vessels and/or embraced total disorder in a bid to reconcile the tensions of the present. Sure, there was comfort food par excellance courtesy of Frederick Wiseman and Tran Anh Hung, but even their films served as tasty reminders that great cinema always takes us just a little further into the future — or into ourselves — than we can dare to imagine without it.

Here are IndieWire’s picks for the 25 best movies of 2023.

This article includes contributions from Carlos Aguilar, Christian Blauvelt, Jude Dry, Sophie Monks Kaufman, and Ryan Lattanzio.

-

25. “Beau Is Afraid” (dir. Ari Aster)

Image Credit: A24 A sickly picaresque guilt trip that stretches a single Jewish man’s swollen neuroses into a three-hour nightmare so queasy and personal that sitting through it feels like being a guest at your own bris (in a fun way!), Ari Aster’s seriocomic “Beau Is Afraid” may not fit the horror mold as neatly as his “Hereditary” or “Midsommar,” but this unmoored epic about a zeta male’s journey to reunite with his overbearing mother eventually stiffens into what might be the most terrifying film he’s made so far.

Mileage will vary on that score — the scares are typically less oh shit Toni Collette is spidering across the ceiling and more oy gevalt, Joaquin Phoenix’s enormous prosthetic testicles are causing me to squirm under the weight of my own emotional baggage — but anyone who would sooner die for their mom than answer the phone when she calls should probably mix a few Zoloft into their popcorn just to be safe. Those people should brace for a movie that triggers the same cognitive dissonance from the moment it starts, often relying on that friction to propel its plot forward in lieu of dramatic conflict. Most of all, they should brace for a movie they’ll love in an all too familiar way: unconditionally, but with a nagging exasperation over why it feels so hard. —DE

-

24. “Godland” (dir. Hlynur Pálmason)

Image Credit: Sideshow The life and work of writer-director Hlynur Pálmason seems suspended in a liminal space between his homeland of Iceland and the neighboring Scandinavian nation of Denmark, where he studied filmmaking and has now raised a family. And nowhere is that interstitial status more evidently reflected than in his third and finest feature yet, “Godland,” an arrestingly beautiful and philosophically imposing bilingual historical drama about the arrogance of mankind in the face of nature’s unforgiving prowess, the inherent failures of colonial enterprises, and how these factors configure the cultural identities of individuals.

As in Pálmason’s previous studies of seemingly mild-mannered male characters on the brink of a violent outburst, “Winter Brothers” and “A White, White Day,” his latest maps the mental and physical decay of Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove), a 19th century Danish priest of the Lutheran faith tasked with overseeing the construction of a church in a remote corner of Iceland, at the time still a territory part of the Kingdom of Denmark. What follows is a voyage of visual splendor and divine contemplation, terrifying and breathtaking in equal measure. —CA

-

23. “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” (dir. Kelly Fremon Craig)

Image Credit: Lionsgate Films Judy Blume never talked down to kids or adults, and such is the spirit that drives Kelly Fremon Craig’s film adaptation of the author’s most beloved book, “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.” It’s an adaptation that Blume long resisted, at least before “The Edge of Seventeen” filmmaker and her mentor and producer James L. Brooks pitched their idea to her, but Blume’s book translates beautifully to the big screen with same zip, pep, and good humor of Blume’s books.

A wonderfully specific story about a pre-teen girl eagerly anticipating the arrival of her first period, “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” is also a story that doubles as a deeply universal tale of searching for life’s meaning at any age. That’s the magic of Blume’s books: Ostensibly for kids and young adults, the author treats all of her characters and their concerns as being worthy of examination. The stakes might seem different for, say, Margaret’s mom worrying about reconnecting with her parents after they cut her off long ago over her choice of husband versus her sixth-grade daughter agonizing over when she’ll need her first bra, but here these people and their problems are all important, all vital, and all worthy of respect. “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” isn’t just the best Blume adaptation currently available, it’s also an instant classic of the coming-of-age genre, a warm, witty, incredibly inspiring film that is already one of the year’s best. —KE

-

22. “Earth Mama” (dir. Savanah Leaf)

Image Credit: A24 Learn the names Savanah Leaf, first-time feature filmmaker, and Tia Nomore, first-time feature actress, right now, because their debut film “Earth Mama” is a shimmering stunner. A former Olympic volleyball athlete, Leaf has a canny eye for locating the subversion and beauty within a welfare-system drama about a single mother fighting for her life and children. What sounds, on paper, like a challenging sit is actually a wondrous 97-minute feature, whose director and star are obviously poised for greatness.

Any film tackling the petty and punishing bureaucracies of the foster care system risks wading into melodrama or cliche, but “Earth Mama” largely avoids those rookie traps, and with an unpredictable and fiercely focused actress at its roots. Leaf searched far and wide for a Bay Area non-actor to embody Gia, a young Black mother whose son and daughter from an all-but-nonexistent father are in foster-care limbo while she recovers from drug addiction and has barely a dollar to her prepaid cell phone credits. Tia Nomore, frequently seen on the Bay Area freestyle battle-rap circuit, had been training to become a doula for Black families when she was cast, and her personal connection runs through the material. –RL -

21. “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” (dir. Joaquim Dos Santos & Kemp Powers & Justin K. Thompson)

Image Credit: Sony Pictures “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” is awash in stories — its first five or so minutes, an ostensible prologue, is a dynamic tragedy in miniature, and that’s just the first five minutes — all built around an idea one of its characters tosses out during a similarly information-packed voiceover: They’re going to “do things differently.” It’s precisely what the film’s predecessor, the rightly Oscar-winning “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” did four years ago, taking a well-worn concept (a Spider-Man origin story? again?) and turning it into an actual masterpiece built on a wealth of stories, new and old, told with legitimate energy and innovation. And it’s what Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson attempt to replicate in their sequel, an aim that pays off mightily.

“Into the Spider-Verse” was astute and funny, complicated and emotional, unique and daring, and its sequel only grows and expands on those aims. If the first film showed what superhero movies could be, “Across the Spider-Verse” goes even further: It shows what they should be.

In a genre built on the literally super and special, these films are unafraid to stand out and do something truly different, something that pushes the limits, to show the genuine range available to this subset of stories and feel damn good in the process (and look, dare we say, even better). —KE

-

20. “La Chimera” (dir. Alice Rohrwacher)

Image Credit: NEON The third and most romantic installment in Rohrwacher’s informal trilogy exploring the relationship between Italy’s past and present, “La Chimera” finds the Tuscan filmmaker returning to the rustic charm and eternal regret of “The Wonders” and “Happy as Lazzaro” in order to stretch them across a richly textured canvas that spans from ancient Etruria to “The Crown.”

It begins with a man played by Josh O’Connor (never better) as he dreams of the woman he loved and lost. His name is Arthur, her name was Beniamina, and there is no hope of them reuniting on this mortal coil. But Arthur isn’t one to give up. Legend tells of a buried door that connects this world to the next, and this surly archaeologist is so hellbent on finding it that he’s become the leader of a ragtag gang of tombarolis — lovable grave-robbers, essentially — in the small village where his Beniamina once lived. He offers the group his sorcerer-like ability to dowse the location of ancient treasures, and in return they do the digging for him. What he ultimately turns up is a lush and lived-in adventure that beats Indiana Jones at his own game while posing the question that Rohrwacher has been circling for so long: Does the past belong to everyone, or does it belong to no one? —DE

-

19. “Kokomo City” (dir. D. Smith)

Image Credit: D. Smith/Courtesy of Sundance To say “Kokomo City” is about the lives of four Black trans sex workers would be true, but it doesn’t give a full picture of its artistry. Making a triumphant directorial debut, filmmaker D. Smith also shot and edited her gorgeous black and white film, adding a host of original songs to her eclectic score as well. Smith employs a lyrical photographic style reminiscent of “Hale County This Morning, This Evening” with a touch of “Shakedown,” but gives her subjects enough space to express themselves that a satisfying character study emerges. In intimate conversations that typically only happen behind closed doors, Liyah, Daniella, Koko, and Dominique share their thoughts on living stealth, what led them to sex work, and the hypocrisy of the men who see them on the down low. It’s as if they’re speaking to a friend (and maybe they are), using a shorthand that forces the viewer to keep up or risk missing the jokes.

Smith often shoots the women from below, placing herself on the floor at their feet, so they hover like queens above the camera. Sometimes, she’ll use a painful anecdote to narrate an erotic photoshoot on a bed, showing the girls luxuriating in their femininity. She interviews a few trans-attracted men, too, and cuts their energetic sermons with footage of a graceful male ballet dancer. The film’s electrifying final shot feels like both a provocation and a celebration; a full-throated embodiment of the bravado and beauty we’ve just been entrusted to witness. May audiences be humble enough to recognize the privilege. —JD

-

18. “Pacifiction” (dir. Albert Serra)

Image Credit: Grasshopper Film It would be a severe understatement to say that Albert Serra’s Polynesia-set “Pacifiction” avoids the touristic travel-porn clichés of most films about foreigners in a tropical locale. A drifting and rigorously introspective study of colonialism at the edge of apocalypse, “Pacifiction” stars Benoît Magimel as De Roller, dispatched from Paris to serve as the High Commissioner of a country that’s still controlled as a vestige of the French empire. Over the course of the film’s droning 163-minute running time, De Roller’s rudderless existence is capsized — gently at first, and then with soul-crushing force — by rumors that France is preparing to resume nuclear testing near his adopted island nation.

Serra has invoked the ’70s conspiracy thrillers of Alan J. Pakula when talking about “Pacifiction,” but the specter of nuclear weapons testing isn’t what the film is “about” as much as it contributes to an atmosphere of uncertainty and fragility. It’s a narrative throughline on which Serra hangs other issues and ideas in this very episodic movie. Think of a Frederick Wiseman documentary but as a narrative feature; Serra almost made it like a documentary, filming 180 hours of footage (via three cameras at once for each scene, so really 540 hours of footage), and with the script revised and improvised on the fly.

“Pacifiction” is far too oblique to be fully an heir to the Pakula conspiracy thriller tradition. After all, it’s possible weapons testing will never resume here. But isn’t it disturbing enough that it’s considered at all? “Pacifiction” is vital because it’s a movie for a culture constantly patting itself on the back but in desperate risk of repeating all its previous mistakes. Where every little bit of progress is imperiled. We delude ourselves into thinking colonial exploitation was left behind in the 20th century (along with nuclear tests). Or maybe we choose to ignore what’s right in front of us. —CB

-

17. “Love Life” (dir. Kōji Fukada)

Image Credit: Oscilloscope Films An enormously poignant melodrama told at the volume of a broken whisper, Kōji Fukada’s “Love Life” represents a major breakthrough for a filmmaker (“A Girl Missing,” “The Real Thing”) who’s found the perfect story for his probing but distant style. In that light, it doesn’t seem incidental that “Love Life” is a story about distance — specifically the distance between people who reach for each other in the wake of a tragedy that strands them far away from themselves.

Inspired by the plaintive 1991 Akiko Yano song of the same name (in which the Japanese singer croons, “Whatever the distance between us, nothing can stop me from loving you”), “Love Life” introduces us to a domestic idyll that it disrupts with a deceptive casualness typical of Fukada’s work. The bloom comes off the rose slowly at first, and then all at once in a single moment of everyday awfulness.

While “Love Life” has its fair share of sharply written heart-to-hearts, many of its most touching moments (and all of its most telling ones) hinge on a certain kind of emotional geography. It’s the way that Park, once unhoused, begins sleeping in the empty apartment across from Taeko and Jiro once the latter’s parents move out of town. It’s the reflections of sunlight that cut across Jiro’s eye-line from across the courtyard, and the way that Taeko is seen speaking to someone just out of frame as the messiness of her feelings spills over the clear borders we’re supposed to dig around them. –DE -

16. “R.M.N.” (dir. Cristian Mungiu)

Image Credit: IFC Films Chekhov’s gun has seldom fallen into hands as steady and menacing hands as in Cristian Mungiu’s poorly titled, expertly staged “R.M.N.,” which finds the elite Romanian auteur extrapolating the personal tensions that gripped his previous work (e.g., “Beyond the Hills” and the Palme d’Or-winning “4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days”) across an entire Transylvanian village. The result is a socioeconomic crucible that carefully shifts its weight to the same foot that Mungiu always loves to rest on your throat; a slightly over-broad story of timeless xenophobia baked full of local flavor and set right on the cusp of a specific moment in the 21st century.

When bull-headed Matthias (Marin Grigore) quits his job at a German slaughterhouse by assaulting his racist boss, he has no choice but to return to the financially dispossessed hometown he’d left when the local mine shut down — the same place where a trio of migrant workers from Sri Lanka are about to be scapegoated for everything that goes wrong during a brutal winter. Pulling harder and harder at the tension between complex socioeconomic forces and the simple human emotions they inspire, “R.M.N.” masterfully spins an all too familiar migration narrative into an atavistic passion play about the antagonistic effects of globalization on the European Union. It will take your breath away. —DE

-

15. “Killers of the Flower Moon” (dir. Martin Scorsese)

Image Credit: Apple Films Martin Scorsese may like to think of “Killers of the Flower Moon” as the Western that he always wanted to make, but this frequently spectacular American epic about the genocidal conspiracy that was visited upon the Osage Nation during the 1920s is more potent and self-possessed when it sticks a finger in one of the other genres that bubble up to the surface over the course of its three-and-a-half-hour runtime.

The first and most obvious of those is a gangster drama in the grand tradition of the director’s previous work; just when it seemed like “The Irishman” might’ve been Scorsese’s final word on his signature genre, they’ve pulled him back in for another movie full of brutal killings, bitter voiceovers, and biting conclusions about the corruptive spirit of American capitalism. But if the “Reign of Terror” sometimes proves to be an uncomfortably vast backdrop for Scorsese’s more intimate brand of crime saga, “Killers of the Flower Moon” excels as a compellingly multi-faceted character study about the men behind the massacre. Over time, it becomes the most interesting of the many different movies that comprise it: A twisted love story about the marriage between an Osage woman (the indomitable Lily Gladstone) and the white man who — unbeknownst to her — helped murder her entire family so that he could inherit the headrights for their oil fortune (Leonardo DiCaprio, giving the best performance of his career as the dumbest and most vile character he’s ever played).

Finding the right balance in this story is a challenge for a filmmaker as gifted and operatic as Scorsese, whose ability to tell any story rubs up against his ultimate admission that this might not be his story to tell. And so, for better or worse, Scorsese turns “Killers of the Flower Moon” into the kind of story that he can still tell better than anyone else: A story about greed, corruption, and the mottled soul of a country that was born from the belief that it belonged to anyone callous enough to take it. —DE

-

14. “Oppenheimer” (dir. Christopher Nolan)

Image Credit: Universal At first, I thought that if J. Robert Oppenheimer didn’t exist, Christopher Nolan would probably have been compelled to invent him. The exalted British filmmaker has long been fixated upon stories of haunted and potentially self-destructive men who sift through the source code of space-time in a desperate bid to understand the meaning of their own actions, and so the “father of the atomic bomb” — a theoretical physicist whose obsession with a twilight world hidden inside our own led to the birth of the modern age’s most biblical horrors — would seem to represent an uncannily perfect subject for the “Tenet” director’s next epic. And he is. In fact, Oppenheimer is so perversely well-suited to the Nolan treatment that I soon began to realize I had things backwards: Christopher Nolan only exists because men like J. Robert Oppenheimer invented him first.

Which isn’t to overstate the degree to which Nolan’s first biopic feels like some kind of grandiose self-portrait (even if the Manhattan Project sequences can seem broadly analogous to the filmmaking process, as large swaths of “Inception” and “The Prestige” did before them), nor to suggest that the director sees himself in the same regard as the man he describes in the “Oppenheimer” press notes as “the most important person who ever lived.” It’s also not to glibly conflate one of the most controversial figures of the 20th century with one of the most controversial figures on the r/Movies subreddit, even if the industry-changing success of “Batman Begins” surely inspired a “now I am become death” moment of Nolan’s very own.

Paced like it was designed for interstellar travel, scripted with a degree of density that scientists once thought purely theoretical in nature, and shot with such large-format bombast that repetitive scenes (or at least Nolan-esque slices) of old politicians yelling at each other about expired security clearances hit with the same visceral impact as the 747 explosion in “Tenet,” “Oppenheimer” is nothing if not a biopic as only Christopher Nolan could make one. Indeed, it would seem like the ideal vehicle for Nolan’s career-long exploration into the black holes of the human condition — the last riddles of a terrifyingly understandable world. –DE -

13. “The Delinquents” (dir. Rodrigo Moreno)

Image Credit: MUBI Arguably the first slow cinema heist movie, Rodrigo Moreno’s dreamy and discursive “The Delinquents” might kick off with one of the most low-key bank robberies anyone has ever attempted, but it’s hard to overstate how thrilling it feels once the thief finally tells us about what he stole.

A middle-aged employee at a musty Buenos Aires bank that seems to have gotten stuck in the 1970s, Morán (Daniel Eliás) decides to walk out of the vault one day with a few dozen bricks of American cash in his backpack — the exact amount he would have earned before retirement if he worked every day for the next quarter of a century, and he plans to hide the money before doing jail time for his crime. It’s just basic math: For the same payout, Morán could either spend three years in prison, or 25 years at the bank. He doesn’t want to be rich, he just wants to be free. Free from capitalism, free from its lopsided farce of a work-life balance, and free from the strictures of conventional thinking, which don’t just affect our schedules but also how we see the world itself. That might seem a foolish goal in a film less creatively unbound than the one Moreno has made here, but this playful three-hour reverie is so happily unmoored from the expectations of everyday storytelling that it’s tempting to think Morán might not be tilting at windmills after all.

Short by the standards of some recent Argentinian cinema, but still breezy and unhurried in a way that invites your mind to wander around without being leashed to the usual obligations of plot, “The Delinquents” is less interested in the details (or dramatic consequences) of Morán’s theft than it is in how the very idea behind it begins to remap Román’s entire worldview. The gym bag full of money that he stuffs into his bedroom closet doesn’t provoke his greed so much as his imagination. When we’re first introduced to Morán, he’s determined to escape the rat race in which the first thing people ask each other is invariably some variation on “what do you do for work?,” as if that were the only meaningful way of assessing someone’s value. So much as “The Delinquents” can be strictly defined as a film about anything, it’s a film about the search for a better question. Answers are off the table here, all the way through the movie’s wide, wide, wide open ending, but our frame of reference expands a bit further with every passing scene. —DE

-

12. “Barbie” (dir. Greta Gerwig)

Image Credit: Warner Bros. Greta Gerwig’s zeitgeist-changing smash hit opens, of course, with an homage to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.” A dazzling sunrise stretches over a barren desert, populated exclusively with sad-eyed Dust Bowl-era girls and their unblinking baby dolls, as Helen Mirren (!!) narrates us through what life was like pre-Barbie. It wasn’t just boring (though it was certainly boring), but it was limited (oh, was it limited). For so many little girls, dolls were only ever baby dolls, which meant that their playtime could only ever revolve around motherhood, servitude, and no fun whatsoever.

But just as Kubrick’s apes eventually met by an alien monolith that utterly changed their world and worldview, Gerwig’s little girls are about to be descended upon by a world-altering and brain-breaking new entity: a giant, one might even say monolithic, Barbie doll, in the form of a smiling Margot Robbie, kitted out like the very first Barbie doll ever made. And thus spake Barbie. That’s where Gerwig’s funny, feminist, and wildly original “Barbie” begins. It will only get bigger, weirder, smarter, and better from there.

“Barbie” is a lovingly crafted blockbuster with a lot on its mind, the kind of feature that will surely benefit from repeat viewings (there is so much to see, so many jokes to catch) and is still purely entertaining even in a single watch. It’s Barbie’s world, and we’re all just living in it. How fantastic. –KE

-

11. “A Thousand and One” (dir. A.V. Rockwell)

Image Credit: Focus Features There are two bruising lines that bookend first-time feature director A.V. Rockwell’s “A Thousand and One,” a vivid portrait of Harlem life from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s.

“There’s more to life than fucked-up beginnings,” Inez, a woman living life in New York on her own terms and brilliantly played by R&B super-artist/actress Teyana Taylor, tells her young son Terry (Aaron Kingsley Adetola). She has kidnapped him out of the foster care system, which has kept them separated after her stint in Rikers Island beginning in 1993, and now hopes to give him a better life. But at the end of the movie, after a decades-spanning, bittersweet bond forms and fizzles between them and shattering revelations are had, she tells the older Terry (Josiah Cross), “I fucked up. Life goes on. So what?”

A searing protest against the inhumanity of gentrification in a city whose policies and policing are already so punitive towards poor Black families, “A Thousand and One” serves as a sobering reminder of how fucked-up beginnings can hopefully bring about better endings. Cross is crucial to the success of the film’s unforgettable final scenes, but it’s Taylor who anchors Rockwell’s direction and screenplay with her powerhouse performance. Taylor has worked with the likes of Tyler Perry in comedies, but her turn here — as fiercely committed to the character as Inez is to Terry — signals a major dramatic talent. —RL

-

10. “The Zone of Interest” (dir. Jonathan Glazer)

Image Credit: A24 Holocaust cinema has so implicitly existed in the shadow of a single question that it would no longer seem worth asking if not for the fact that it’s never been answered: How do you depict an atrocity? Is seeing necessary for believing, or are some things too unfathomable to adequately capture on camera?

A Holocaust drama that’s defined by its rigorous compartmentalization and steadfast refusal to show any hint of explicit violence, Jonathan Glazer’s profoundly chilling “The Zone of Interest” stands out for how formally the film splits the difference between the two opposite modes of its solemn genre — a genre that may now be impossible to consider without it. No Holocaust movie has ever been more committed to illustrating the banality of evil, and that’s because no Holocaust movie has ever been more hell-bent upon ignoring evil altogether. There is a literal concrete wall that separates Glazer’s characters from the horrors next door (those characters being the commandant of Auschwitz and his family), and not once does his camera dare to peek over it for a better look.

The authorless quality of Glazer’s images frees the characters within them from the emptiness of moral judgment. The evil on display is never the least bit in doubt, but its failure to recognize itself as such is only so able to take shape in the absence of its limiting obviousness. By the end, “The Zone of Interest” insists that all of history’s most abominable moments have been permitted by people who didn’t have to see them, and while the film’s ultimate staying power has yet to be determined, its vision of normality is — as Hannah Arendt once described that phenomenon — “more terrifying than all the atrocities put together.” —DE

-

9. “All of Us Strangers” (dir. Andrew Haigh)

Image Credit: Searchlight Based on a 1987 Taichi Yamada novel that writer-director Andrew Haigh has tenderly queered in a way that resonates with his own experience, “All of Us Strangers” begins with a premise so poignant that even the slightest miscalibration could make the whole thing ring false. Good thing the movie doesn’t have any of those. Andrew Scott of “Fleabag” fame stars as a lonely gay screenwriter named Adam, who’s all too at home in the eerie new London high-rise where he seems to be one of the only two residents. And wouldn’t you know it, the other renter — Harry — looks an awful lot like Paul Mescal, who plays the part with a sex-forward puckishness that disguises the same pain that it advertises with every glance (no actor on Earth is as good at selling an open wound). As the two men begin to let each other into their apartments and lives, Adam begins writing a script about his childhood in suburbia, a process that sees him visiting the house where he (and Haigh!) grew up, and communing with the spirits of his parents (Jamie Bell and Claire Foy) who died before they really got to know him.

And so the stage is set for a plaintive ghost story whose lo-fi approach to the afterlife cleaves much closer to the wistfulness of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s “After Life” than it does the sentimentality of “Field of Dreams.” Which isn’t to suggest that “All of Us Strangers” isn’t a nuclear-grade tearjerker, because it is most definitely that, especially once Adam’s burgeoning relationship with Harry begins to compound the one he resurrects with his parents. But Haigh tells this potentially maudlin story with such a light touch that even its biggest reveals hit like a velvet hammer, and his screenplay so movingly echoes Adam’s yearning to be known — across time and space — that the film always feels rooted in his emotional present, even as it pings back and forth between dimensions. —DE

-

8. “Anatomy of a Fall” (dir. Justine Triet)

Image Credit: NEON They say trends come in threes. And so, nipping on the heels of Alice Diop’s “Saint Omer” and Cedric Kahn’s Directors’ Fortnight breakout “The Goldman Case,” Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or-winning “Anatomy of a Fall” make a compelling case that the courthouse has become the most fertile ground in contemporary French cinema, offering incisive auteurs both motive and opportunity to put social structures on trial. As it calls the institution of marriage to the stand, Triet’s piercing film holds the ambient tensions and illogical loose ends of domestic life against the harsh and rational light of a legal system that searches for order in chaos.

Rounding out her own impressive hat trick, “Toni Erdmann” and “The Zone of Interest” star Sandra Hüller dazzles in a role clearly written with the performer in mind. She plays Sandra, a German-born, France-based bisexual novelist accused of killing her male partner in a way eerily foretold by one of her novels. And if that description calls to mind another icy-blond (in a performance, incidentally, that also shook the Cannes Film Festival, back in 1992), the echo is both wholly intentional and entirely irrelevant. Indeed, “Anatomy of a Fall” is filled with such anti-portents –coincidences or clues, depending on who you ask, echoes or empty noise, depending on who’s listening.

“Anatomy of a Fall” is never really about the trial that follows; at its searing best, the film tracks the destruction of a family with cold precision. If an artist relies on memories, why not also share nightmares? Why not build a polar vortex that crushes fact under fiction, that lifts from last night’s argument, today’s viewing of a ’90s classic and tomorrow’s worst fears? It’s a cyclone that sends the mind soaring, and primes the heart for a hefty fall. —BC

-

7. “Passages” (dir. Ira Sachs)

Image Credit: MUBI Not long into Ira Sachs’ “Passages” — sometime all too shortly after a restless, self-involved filmmaker (Franz Rogowski) leaves his much softer husband (Ben Whishaw) for the earthy and new woman (Adèle Exarchopoulos) he meets at a dance club after a stressful day of shooting — Tomas launches into a post-coital chat by telling Agathe that he’s fallen in love with her. “I bet you say that a lot,” she replies, bluntly sniffing out his bullshit in a way that suggests this Parisian school teacher doesn’t understand how far most artists would go to convince their audience of an emotional truth. “I say it when I mean it,” Tomas counters. “You say it when it works for you,” Agathe volleys back. They’re both right, but that’s not the problem. The problem is that they’re saying exactly the same thing.

A signature new drama from a director whose best work (“Keep the Lights On,” “Love Is Strange”) is at once both generously tender in its brutality and unsparingly brutal in its tenderness, the raw and resonant “Passages” is the kind of fuck around and find out love triangle that rings true because we aspire to its sexier moments but see ourselves in its most selfish ones. –DE -

6. “Poor Things” (dir. Yorgos Lanthimos)

Image Credit: Searchlight Emma Stone is a woman who gets to start from scratch in Yorgos Lanthimos’ unbound and astonishing new feature, “Poor Things.” For most of us, life is comprised of knowledge and circumstance that take decades to accumulate until we die.

For Stone’s Bella Baxter, that process happens in very fast motion, thanks to a reanimating procedure that finds her, once a dead woman floating in a river, now alive again with her unborn child’s brain inside her head. Bella, née Victoria, is a living breathing tabula rasa unfettered by societal pressures, propriety, or niceties. And Stone, in her most brazenly weird performance to date, plays her like a toddler taking its first steps and saying its first words — until by the end of “Poor Things” she’s speaking fluent French and studying anatomy, her eyes and ears full of worldliness.

Boldly realized with taffy-colored production design, brain-bending sets stuffed with enough easter egg unrealities to fill the most difficult 5,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, and wildly over-the-top Victorian costumes that look as if made by a schizoid seamstress on too many tabs of acid, “Poor Things” is also hysterically funny and the raunchiest movie you’re likely to see all year. Lanthimos makes a sexually graphic picaresque that’s part Terry Gilliam, part Ken Russell, about Bella’s pursuit of pleasure but also her selfhood in a patriarchal world. Mark Ruffalo, Willem Dafoe, and Ramy Youssef each provide overwhelmingly hilarious turns as the men in Bella’s life — her ridiculous lover, her creator, and her potential husband, respectively.

“Poor Things” is the best film of Lanthimos’ career and already feels like an instant classic, mordantly funny, whimsical and wacky, unprecious and unpretentious, filled with so much to adore that to try and parse it all here feels like a pitiful response to the film’s ambitions. It’s proof that whatever weird alchemy Stone and Lanthimos are vibing on after “The Favourite” is the real deal. —RL

-

5. “May December” (dir. Todd Haynes)

Image Credit: Netflix A heartbreakingly sincere piece of high camp that teases real human drama from the stuff of tabloid sensationalism, Todd Haynes’ delicious “May December” continues the director’s tradition of making films that rely upon the self-awareness that seems to elude their characters — especially the ones played by Julianne Moore.

Here, the actress reteams with her “Safe” director to play Gracie Atherton-Yoo, a lispy former school teacher who became a household name back in 1992 when she left her ex-husband for one of her 13-year-old students. Now it’s 2015, the situation has normalized somewhat, and Gracie and Joe (a dad bod Charles Melton) have been together long enough that their youngest children are about to graduate high school. Their scandalous romance has settled into suburban reality… or so it would appear. Alas, the past isn’t quite ready to release its grip on these crazy kids just yet, especially once Gracie decides to roll out the welcome mat for a breathy TV actress who’s preparing to play her in an indie film about the scandal (Natalie Portman (phenomenally on pointe in a merciless performance). Inviting the stranger into her life seems innocent enough, but Gracie doesn’t quite understand what else she’s inviting into her life at the same time.

Written by Samy Burch, “May December” is a catty-as-fuck dark comedy that deepens Haynes’ longstanding obsession with performance while poking fun at the kind of actresses he clearly loves so much. The director’s tonal playfulness has sometimes been overshadowed by the unerring consistency of his emotional textures, but here, in the funniest and least “stylized” of his films, it’s easier than ever to appreciate his genius for using artifice as a vehicle for truth. —DE

-

4. “The Boy and the Heron” (dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Image Credit: GKIDS How does someone follow one of the greatest and most profoundly summative farewells the movies have ever seen? By definition, they don’t. They retire, or they die. Or they retire and then they die. In some rare cases, it even seems like they die because they retired. And then there’s 82-year-old filmmaker and Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, always in a category of his own, who’s formally or informally quit the business no fewer than seven times of the course of his illustrious career, most recently after the 2013 release of his magnum opus “The Wind Rises.” That film — a fictionalized biopic about aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi — ended with someone concluding “we must live,” in spite of all things. Miyazaki’s new last film (for now) asks how, and then offers its own kind of answer.

The story of an angry and grieving child named Mahito who loses his mother in a 1943 hospital fire and then moves to the Japanese countryside so that his father can marry the boy’s aunt, “The Boy and the Heron” kicks into high gear once an Iago-like bird lures Mahito into a parallel universe with promises of reuniting with his mother. Already one of the most beautiful movies ever drawn, Miyazaki’s film becomes transcendent from that point on, resolving into a dream-like adventure that finds its creator nakedly reflecting on his legacy. And while this dream-like warble of a swan song may be too pitchy and scattered to hit with the gale-force power that made “The Wind Rises” feel like such a definitive farewell, “The Boy and the Heron” finds Miyazaki so nakedly bidding adieu — to us, and to the crumbling kingdom of dreams and madness that he’ll soon leave behind — that it somehow resolves into an even more fitting goodbye, one graced with the divine awe and heart-stopping wistfulness of watching a true immortal make peace with their own death. —DE

-

3. “Asteroid City” (dir. Wes Anderson)

Image Credit: Focus Features Like any movie by Wes Anderson, “Asteroid City” is the epitome of a Wes Anderson movie. A film about a television program about a play within a play “about infinity and I don’t know what else” (as one character describes it), this delightfully profound desert charmer — by far the director’s best effort since “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” and in some respects the most poignant thing he’s ever made — boasts all of his usual hallmarks and then some.

A multi-tiered framing device, diorama-esque shot design, and Tilda Swinton affectlessly saying things like “I never had children, but sometimes I wonder if I wish I should have” are just some of the many signature flourishes that you might recognize from Anderson’s previous work and/or the endless parade of A.I.-generated TikToks that imitate his style.

Let’s just say that all of the people in Asteroid City will be more directly confronted with the unknown than anyone in a Wes Anderson film has been before. Imagine if Mr. Fox’s encounter with the wolf on the hill came at the end of the first act instead of the end of the third, or if Steve Zissou came face-to-face with the jaguar shark that ate his friend just a few minutes after the jaguar shark ate his friend. Imagine if any of Anderson’s most resolute yet vulnerable characters — all of whom have devised intricate systems of living in order to impose some degree of control over a chaotic universe — were forced to reckon with their own helplessness right from the start. —DE

-

2. “The Taste of Things” (dir. Tran Anh Hung)

Image Credit: IFC Films There is something to be said for a simple dish made with the best ingredients by a trusted hand. Just as a perfect omelet made by a lover is more satisfying than an eight-hour feast laid on by a Prince, so it follows that a film like “The Taste of Things works, not in spite of, but because it focuses on executing its basic premise with enrapturing attention to detail. This is a story about love and food, which it presents as the same thing.

Sight unseen, it was always a mouth-watering prospect: two delicious French actors – Juliette Binoche as a cook and Benoît Magimel as her long-time lover and food-obsessed employer – feeding each other in Tran Anh Hung’s adaptation of a 2014 graphic novel reputed to be food porn. The promise of this set-up is delivered with gusto as the kitchen of a 19th century French manor house becomes the stage for the most elaborate foreplay you’ve ever seen. What “Call Me By Your Name” did for peaches “The Taste of Things” does for syrup pears. Belonging to a fine tradition of intoxicating food films such as “Babette’s Feast”, “Julie & Julia”, and “Like Water For Chocolate,” “The Taste of Things” pushes the notion of bonding through vittles a step further. Certain dishes are so inscribed by their creators that they act as memory itself, says the film, a sentiment that leaves a beautiful after-taste. —SMK

-

1. “Past Lives” (dir. Celine Song)

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection Of all the writers retreats in all the summer towns in all of New York, he had to walk into hers. As the sun fades on a perfect Montauk night — setting the stage for a first kiss that, like so many of the most resonant moments in Celine Song’s transcendent “Past Lives,” will ultimately be left to the imagination — Nora (an extraordinary Greta Lee) tells Arthur (John Magaro) about the Korean concept of In-Yun, which suggests that people are destined to meet one another if their souls have overlapped a certain number of times before. When Arthur asks Nora if she really believes in all that, the Seoul-born woman sitting across from him invitingly replies that it’s just “something Korean people say to seduce someone.”

Needless to say, it works.

But as this delicate yet crushingly beautiful film continues to ripple forward in time — the wet clay of Nora and Arthur’s flirtation hardening into a marriage in the span of a single cut — the very real life they create together can’t help but run parallel to the imagined one that Nora seemed fated to share with the childhood sweetheart she left back in her birth country. She and Hae Sung (“Leto” star Teo Yoo) haven’t seen each other in the flesh since they were in grade school, but the ties between them have never entirely frayed apart.

On the contrary, they seem to knot together in unexpected ways every 12 years, as Hae Sung orbits back around to his first crush with the cosmic regularity of a comet passing through the sky above. The closer he comes to making contact with Nora, the more heart-stoppingly complicated her relationship with destiny becomes. And with each passing scene in this film (all of them so hushed and sacrosanct that even their most uncertain moments feel as if they’re being repeated like an ancient prayer), it grows easier to appreciate why Nora felt compelled to mention In-Yun on that seismic Montauk night.

On paper, “Past Lives” might sound like a diasporic riff on a Richard Linklater romance — one that condenses the entire “Before” trilogy into the span of a single film. In practice, however, this gossamer-soft love story almost entirely forgoes any sort of “Baby, you are gonna miss that plane” dramatics in favor of teasing out some more ineffable truths about the way that people find themselves with (and through) each other. Which isn’t to suggest that Song’s palpably autobiographical debut fails to generate any classic “who’s she gonna choose?” suspense by the time it’s over, but rather to stress how inevitable it feels that Nora’s man crisis builds to a bittersweet quiver of recognition instead of a megaton punch to the gut. Here is an unforgettable romance that unfolds with the mournful resignation of the Leonard Cohen song that inspires Nora’s English-language name; it’s a movie less interested in tempting its heroine with “the one who got away” than it is in allowing her to reconcile with the version of herself she once left with him as a priceless souvenir.

In January, we wrote that “Past Lives” was destined to be one of 2023’s best films. That may have been a self-fulfilling prophecy, but it turns out we were still selling Celine Song’s transcendent debut a little short. —DE