Editor’s note: This review was originally published at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival. Sony Pictures Classics releases the film in select theaters on Friday, November 24, with a nationwide rollout to follow in early 2024.

The one thing you can’t accuse “They Shot the Piano Player” of is talking down to its audience. Fernando Trueba and Javier Mariscal’s animated documentary about the 1976 disappearance of pianist Francisco Tenorio Jr. demands your absolute attention with its encyclopedic index of talking heads, and pretty much requires you to have substantial existing knowledge of bossa nova and the South American geopolitics of the 1960s and ’70s. Woe to those who do not. The result is an aggravating missed opportunity to tell a story that absolutely needs to be told to an audience that needs to hear it.

Trueba is a legendary director in Spain. Those who don’t know him for his 1992 Academy Award winner for Best Foreign Language Film, “Belle Epoque,” probably do from his 2010 animated team-up with Mariscal, “Chico and Rita.” Trueba’s passion for telling the tragic story of Tenorio, and how it symbolized the end of the artistic freedom of the bossa nova era and the rising, blood-soaked tide of the dictatorships that took over much of South America is obvious: He’s been collecting the interviews featured in “They Shot the Piano Player” for a couple of decades.

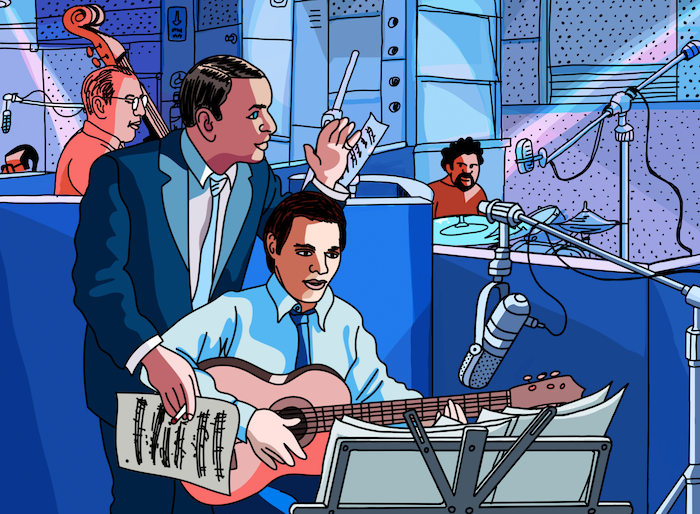

But he gets so caught up in the fine details of the story — what exactly happened to Tenorio? — that he loses sight of why this story matters. Yes, he respects the audience enough to already know why, but that’s an assumption he shouldn’t make — especially of a U.S. audience that’s increasingly unaware of even recent history. A U.S. audience that desperately needs to understand the horrific things its government has done across the hemisphere. To make matters worse, his team-up with Mariscal to render this story in animated “Chico and Rita” style adds layers of distracting detail that further obscure what “They Shot the Piano Player” is trying to illuminate.

Trueba and Mariscal’s framing device brings a star onboard, Jeff Goldblum, to ostensibly enhance the film’s commercial appeal (it’s already been snatched up by Sony Pictures Classics). But it also adds a level of conceptual gamesmanship to the entire film that just confuses matters further: Goldblum plays Jeff Harris, a journalist who wrote a New Yorker article about the 50th anniversary of bossa nova that was praised enough to become a book. Harris, his book editor voiced by Roberta Wallach, and his friend João (Tom Ramos), who takes him to meet various surviving luminaries of bossa nova, are the only fictional characters.

All the people Harris “meets” are interviews that Trueba has himself conducted in real life: It’s a blend of fiction and documentary where the blurring of lines seems especially unnecessary, even dangerous. There’s enough misinformation and ambiguity about what happened during the military dictatorships of Brazil and Argentina already. Clarity, rather than cleverness, should have been the imperative here.

Harris seems to follow an arc much like Trueba himself: He loved bossa nova, but then became obsessed with Tenorio’s disappearance to the point that that tragedy ended up becoming the lens through which he sees the whole movement. He interviews the woman who was with Tenorio right at the end, whose 2:00 a.m. request of him to go out and buy a sandwich or medicine (these details have been obscured by time) sent him out onto the streets of Buenos Aires one night in 1976, never to return. He interviews Tenorio’s wife, who still considers herself his wife rather than widow, as a body was ever found. He interviews some of his artistic collaborators, who remarked on how Tenorio had styled himself as bossa nova’s answer to American jazz great Bill Evans, long-haired, bearded, and capable of a piano technique that’s especially supple and sweet.

Trueba could have spent even more time exploring Tenorio’s artistry — and what exactly made bossa nova such a global craze, beyond a rapid-fire explainer at the beginning featuring an animated rendering of Frank Sinatra — but his disappearance quickly becomes the film’s main focus. This involves another rushed-through primer, this time on Operation Condor, the U.S.-backed effort to install right-wing military dictatorships in most of South America’s countries, starting in the 1950s. And the especially remarkable thing: That these juntas then worked together, ostensibly to squelch communism across the continent in its tracks, but really to assassinate democracy and advance the strategic interests of the U.S. That’s why, when Tenorio disappeared right on the eve of Argentina’s own right-wing coup, which kicked off the seven-year Dirty War that saw tens of thousands of people “disappeared,” it probably was the result of some international intrigue.

Argentina’s junta likely coordinated with Brazil’s junta to end Tenorio’s life, even if there’s no clear reason why: Tenorio was almost totally apolitical, apart from being a member of a musician’s union. When brutal regimes dispense with due process and rule by fiat alone, anything can happen, though. And Trueba and Mariscal spend just enough time on certain elements of this terrible period — how the Argentine government found that the best way to “disappear” people was to fly them over the ocean and drop them into a watery grave, or the very existence of Alfredo Artiz, a particularly prolific executor of state-sponsored murder nicknamed “The Blond Angel of Death” — to make you wish they weren’t giving them such a cursory treatment.

It’s entirely possible “They Shot the Piano Player” would have been better had it been much longer. It also certainly would have been better without animation. There is so much detail in every frame that you might find yourself distracted from what the interviewees are saying altogether: when Harris is “interviewing” Tenorio’s wife, your attention might be captivated by the colorful earthenware, fruit, and wood-burning stove behind her. Then a pastel bluebird lands on the window sill over her left shoulder, and a dog pops his head over a separate window sill over her right shoulder, reaching with its paws into the house. That’s a lot to take in!

Those with even a rudimentary grasp of ’60s Brazilian culture will point at the screen Rick Dalton-style when the book “Vidas Secas” appears or when a poster for Glauber Rocha’s “Black God, White Devil” hangs behind an interviewee. It’s simply too much to take in, especially for an investigation so detailed that basically the only way this movie could work is via home viewing, when you can stop it every time there’s an unexplained reference and take to Wikipedia.

That does a real disservice to the urgency of this story. Somehow as of publication time, like the immortal vampire Pablo Larraín imagined Augusto Pinochet to be in “El Conde,” centenarian Henry Kissinger, perhaps more responsible than anyone else in U.S. government for empowering these juntas, still walks among us. These events are not ancient history. Accountability can still be had, even if it’s just for American viewers to better understand what their government helped unleash. But it’s hard to see how this animation does anything to immerse you deeper in the lives of the people affected here; unlike the empathetic plunge of fellow fall festivals title “The Peasants,” the animation here feels almost entirely like a distancing effect. And what happened in South America in the ’60s and ’70s feels like it’s been kept at a distance far too much as it is.

Grade: C-

“They Shot the Piano Player” played at the 2023 Telluride and Toronto International Film Festivals. It will be released in New York and Los Angeles for one week by Sony Pictures Classics on November 24, followed by a nationwide rollout in early 2024.