As we wrap up our year-end coverage, IndieWire looks back at the people, projects, and ideas that defined 2023 — and what’s coming next.

Chaos often breeds ingenuity, so when it felt like Hollywood had fully shut down during the overlap of the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild strikes, audiences were quick to find a way to satiate their hunger for blockbuster entertainment elsewhere.

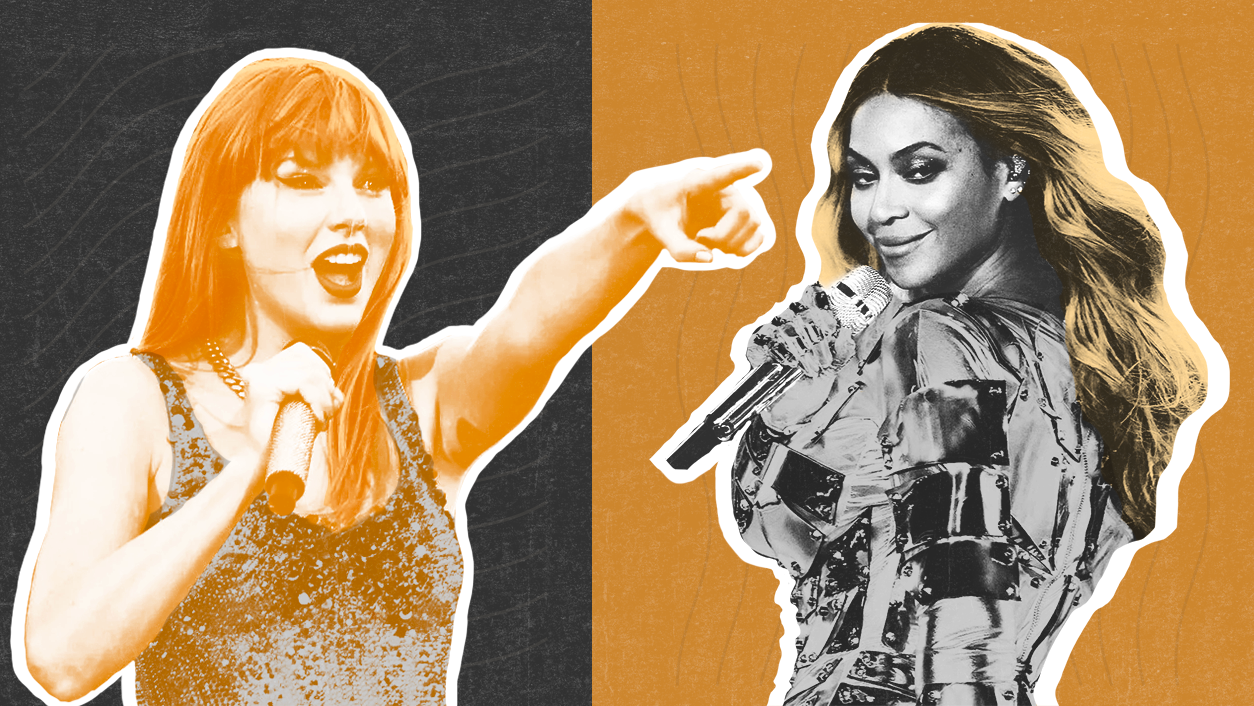

Enter Beyoncé and Taylor Swift, who already had massive tours booked for the summer (as most pop stars are wont to do), though both managed to also market them in a way in which the appeal of attending was not to just pay tribute to an artist they admire, but something far greater: the Renaissance tour and Eras tour became pop cultural events.

In wake of the Barbenheimer phenomenon, pundits did their best to make one-to-one comparisons within the film space for what could follow and build upon the pair of films’ momentum, but with the actual marketing needed to eventize filmgoing cut short by actors’ work stoppage, audiences moved elsewhere. The real inheritors? They revealed themselves naturally.

Taylor Swift’s Eras tour was a canny distillation of decades of varying work by a figure now seen as an All-American icon. Beyoncé’s Renaissance tour was an auteur-driven spectacle meant to shed new light on oft-misinterpreted, or glossed over aspects of American culture. While most were happy to engage with both, the concerts operating under different ethos still had that same “iron sharpens iron” effect we saw from the two top-grossing live action films of the year, released on the same day.

Even prior to them both becoming theatrical releases, Eras and Renaissance made each tour stop feel like something akin to can’t-miss television, viewed through the lens of Instagram Live streams or series after series of unpolished TikToks. While Swift would surprise the crowd each night with a performance of two random songs that did not make the setlist, Beyoncé would constantly debut new, custom-made outfits, sometimes with the intent of showcasing designers local to the city she was in. The Renaissance tour also had the live debut of Blue Ivy Carter, with the 11-year-old quickly upgrading from guest star to series regular, hooking in some viewers that were specifically engaged in tracking her growth as a dancer, performance by performance.

Sure, plenty of music tours have garnered lasting reputations, and even led to iconic documentaries like “Madonna: Truth or Dare,” but none have reached the level of engagement during their runs that the Eras and Renaissance tours had. For them to be made into films felt inevitable, but for those films to be released as early as this fall was an inventive, demand-based decision.

So much of the revenue musicians rely on continues to diminish, hence why top artists find savvy ways to cut costs. Beyoncé is her own manager, Taylor Swift handles her own booking. Though theatrical filmmaking is not their primary industry, it makes sense for them to be the stars most primed to disrupt it.

Swift brokering a deal with AMC Theaters to distribute footage she captured of the Los Angeles shows that closed the United States leg of Eras tour, and assembled into a concert film was genuinely groundbreaking. It is as if she were the one to determine that four-walling was possible on a much higher scale, and it was actually not a foregone conclusion for streaming to be the home of all music documentaries.

Coming under the circumstance of the strike is what also made “Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour” reach new heights within the genre, becoming the highest-grossing concert film of all time. Meanwhile, “Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé,” was clearly planned far more in advance than Swift’s project, incorporating behind the scene footage of the tour as well, and only making the decision to become a theatrical release in the stead of the AMC deal Swift brokered. However, it curries more favor with those more so seeking achievements in the craft of filmmaking.

There is a lot of metaphors to use to compare and contrast Swift and Beyoncé, but another apt one would be to look at the former as Netflix, the most disruptive force in entertainment, best excelling at being all things to all people, while the latter operates more like HBO, more focused on maintaining a prestige label than audience acquisition. Both put out comparable, quality work, but are chasing different ambitions.

The way they eventized the products they offer as entertainers to new, unforeseen heights is not not to reach capitalistic goals, but the byproduct of their achievements furthers conversations around what cultural output is still able to pull an increasingly polarized audience together: How do artists sustain interest in their new work as audiences drown in a deluge of new content coming from all directions? How can filmmakers get their work out there in spite of a devolving studio and theatrical distribution landscape?

Call it a new era, call it a renaissance, but Taylor Swift and Beyoncé gave us a new idea of what a blockbuster event can look like, even before they had released their respective No. 1 debut films.