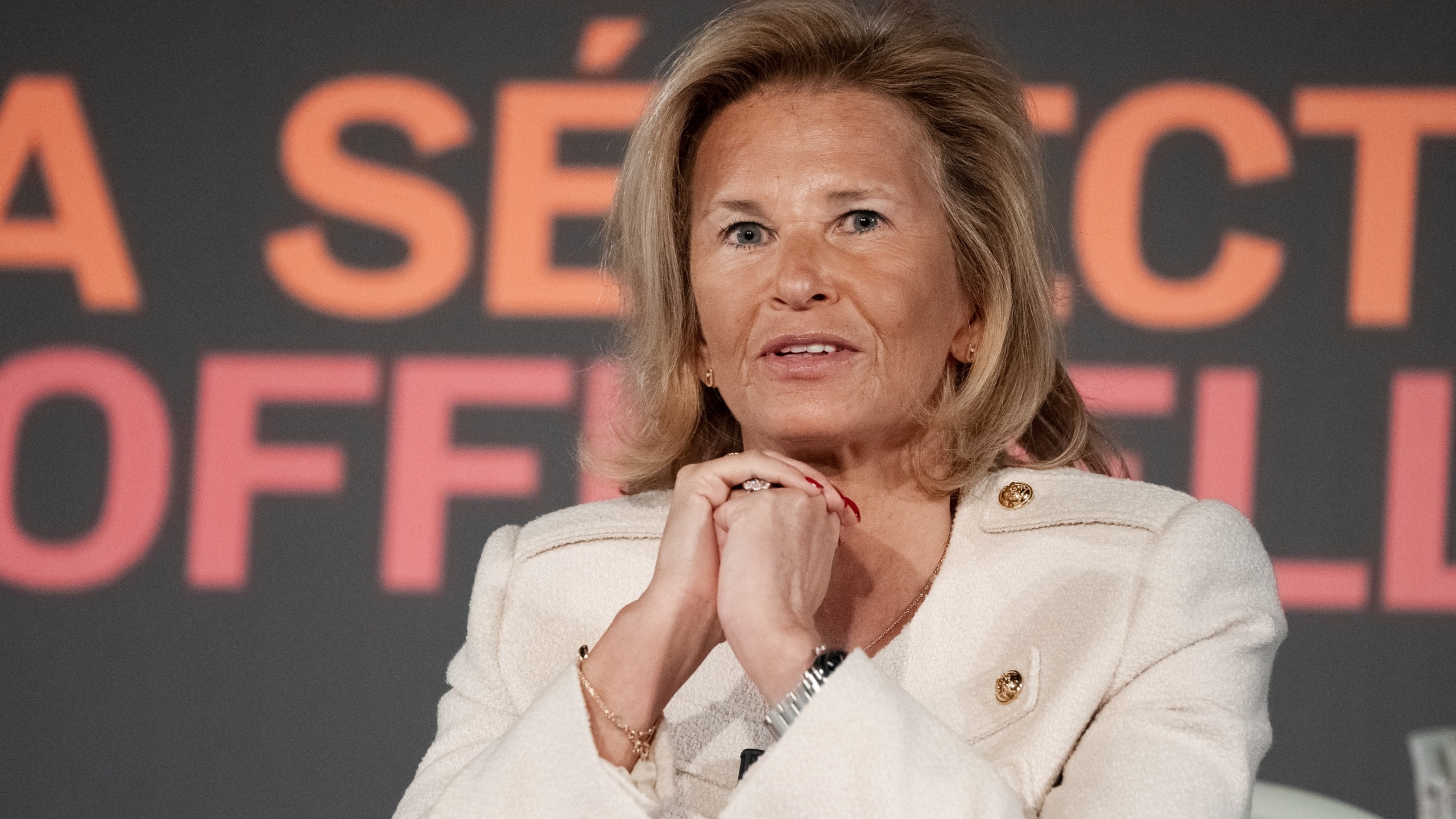

Amidst the daily glamor of the Cannes Film Festival red carpet, two faces are fixtures at the top of the staircase. Artistic director Thierry Fremaux has held his perch there for years, greeting filmmakers as they make their way into the Palais des Festivals. This year, however, he got some new company with festival president Iris Knobloch, who stepped into the role previously filled by Pierre Lescure. Fremaux’s new boss is a different kind of Cannes leader than her predecessors, and not only because she’s the first woman to occupy the position in the festival’s 78 years.

While Fremaux is a diehard cinephile who runs a film museum in Lyon, Knobloch is a seasoned industry executive with a law degree from NYU who served as the president of operations for WarnerMedia in France for nearly 15 years. (It was during that time that she went to Cannes for the 2011 premiere of “The Artist,” which the studio released in France.) Knobloch has attended Cannes for over 25 years, but her ascension to its presidency injected a sudden new dimension into the many questions facing the future of the festival: How would a businesswoman impact the fate of a cultural event best known for celebrating cinema as an art form?

The 60-year-old Knobloch may not know the answer to that question yet, but halfway into the 2023 edition of the festival, she was certain of one thing. “It’s tiresome for all of us,” she told IndieWire from her office on the third floor of the Palais as she sat down for an interview. “Even though I know the festival so well, when you stand on the other side and want to make sure you’re doing the right thing, you put pressure on yourself. It’s interesting when you think you know something, but then you realize you don’t when you’re on the other side.”

Knobloch touched on a wide array of issues at the forefront of the Cannes conversation, from its relationship to streaming platforms to gender parity, whether it would program films from Woody Allen or Roman Polanski, and why she values the Oscar race.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

IndieWire: What did you know about Cannes when you first came in 1998?

Iris Knobloch: I grew up in Germany so I admired the festival from afar. Honestly when I was growing up, if you’d told I’d be standing on those stairs, I’d have said, “Yeah, right.” It’s totally surreal, a ridiculous thought. I watched the festival from afar because it was fabulous. I never imagined I could’ve visited. Then I started working for Warners, and that changed the potential opportunity to come.

What was your relationship to cinema growing up?

I’m a child of Holocaust survivors, so my parents went to the movies almost two times a week, because they didn’t have a youth, so it was a way to recapture those moments. I just tagged along, but it really instilled that kind of knowledge of cinema but also what they taught me through their eyes — that cinema is an important opportunity to get to a broad audience with the right message.

You come from the business side of the industry. Cannes is committed to the art form, including the presentation of movies on the big screen, even as the rise of streaming platforms has endangered it. How do you feel about the conflicts between streamers and exhibitors?

When I was named president last year, obviously I knew that the streaming question was one of the first matters where I would have to have a strong opinion. That was still during a moment last year where we all didn’t know where this all would be going, and I really didn’t quite know what position I would take. But then after the summer I went to see quite a few of my old friends and colleagues in L.A. It was really interesting for me because I understood that the wind had turned and there was a realization that I really believe in, which is that nothing can replace the cultural moment of a movie coming out in theaters. A movie exists differently when you put it in theaters than when you release it on streaming. I said to the board of Cannes, “Honestly, I salute you, because you’ve been holding up the flag at a moment that wasn’t obvious. I think you did the right thing.” Sometimes you have to stand for your convictions.

Do you think the Cannes rule that requires all competition films to have a theatrical release in France will ever change?

You know, I think the industry will continue to evolve, the way we make movies will continue to evolve, and the way we distribute movies will continue to evolve. For me, the streaming question is behind us. I wonder what the next kind of evolution will be. I think Cannes should be at the forefront of this evolution. For me, today — as you see with the investments announced by various platforms — it really feels like streaming has taken its place next to cinema but not replacing it, like every time we have a new technology.

This year, Todd Haynes’ competition film “May December” was bought by Netflix, so it ended up with a competition film at Cannes after all.

I don’t think we should judge that. In this entire debate, what is so important is the public. Many people forget to speak about what the public wants. If you think about that — what does the spectator want? — he wants the choice, the choice to see a film at the movies, on a platform. What that means for release patterns, I don’t have the answer. But we all sometimes forget this when we speak about it. I think this interplay will always exist. I have found often since I came to the festival that there was this wrong perception in the press that Cannes didn’t allow streamers to come. The truth is when you come to Cannes, you don’t need to release in competition. Scorsese didn’t want to be in competition.

But most people want it, don’t they?

I don’t think that’s true. I was at a studio. What you want is visibility. The truth is, honestly, will people really know if it was in competition? It’s a filmmaker choice. The filmmakers should decide. But Netflix can always submit films to Cannes. They just made a decision not to.

Cannes navigates cultural conversations differently than in the U.S. It’s not clear based on anything we’ve heard whether the festival would screen, say, Woody Allen or Roman Polanski films. Where do you fall on those sort of debates?

I think the movies selected in Cannes are always a reflection of society. In a way, they invite — directly or indirectly by what they tell and who participates in them — debates that are today’s debates. I think Cannes should be a place to have these debates. It’s OK to disagree. I don’t think Cannes should take the easy way out on these topics, but it should face these debates and have these conversations. I actually think it’s one of the roles of Cannes to not avoid controversy. I also strongly believe that one of the fundamentals of Cannes is the independence of the selection. The selection should look at the quality of the work. The festival stands for cinematographic excellence and that’s what it should look at. And it should stand for the freedom of creation. That may attract controversy and debate, but I think that’s healthy.

Fine, but would you be OK with a Woody Allen or Roman Polanski film playing at the festival?

They haven’t been presented to us, so I didn’t have to make a decision. [laughs]

Hypothetically, then.

I think it’s very difficult. It has to be decided on a case by case basis. With these cases, I think it’s very clear to say these fundamentals apply. But there will always be gray areas and you will not make everybody happy. It’s not easy. It’s interesting that the standards on how people view these things are different. What may be OK here is not OK there. People have to accept that. But let’s see.

So there’s no firm policy on those directors or others.

No, there’s no firm policy, which I find right. I think it’s good. We had this conversation with the board and we felt that every situation is different.

In 2018, Fremaux signed a pledge to work towards gender parity at the festival. It’s not there yet. How do you feel about the pressure to program more women directors at the festival, especially in competition?

I really feel that the selection committee should look at a movie without thinking about who made it, which country it’s coming from. I really think that’s hugely important. I know that quotas can be helpful, but I also know that quotas are sometimes not easy for women because people may feel they aren’t there for the right reasons. I have lived that in my life. I believe for Cannes, it should always be for the work of art and the rest should have blinders around it.

The truth is where I think we and all the festivals should play a role is this: The 33 percent representation of women that we have this year is a reflection of where the industry is. We are at the end of the chain. We have to look at the beginning. We still don’t have enough female filmmakers. They still have more trouble getting financing, more trouble getting entrusted with big projects, and the question I am asking myself now that I’m here is how I can help try and make a difference at the beginning. I think when we start to improve that war, it will be natural to have more women at the end, and it’s still not there. I don’t have the answer yet. I love what our partners do with Women in Motion because women need the spotlight and more confidence in themselves, so whatever we can do to help them is important. We should not start there and not do quotas.

Adele Hanele made headlines ahead of this year’s edition by referring to Cannes as a “festival for rapists” that protects abusers. What do you make of that characterization?

She has an opinion. I’m not sure I can follow her thinking. I know that Cannes has very high standards on defending what’s right and women. So I find that this is actually getting too much attention.

You worked at a major U.S. studio. Why should big American companies value Cannes?

I’ve been thinking about that a lot now that I’m on this side. I think that people need human connections and just marketing a movie with a trailer and blasting it out doesn’t create the same human connection that I felt here with Harrison Ford or DiCaprio. It’s not just about visibility. It’s about the human connection that comes with Cannes. I feel that it brings a different life to a movie. If you think about last year with “Top Gun: Maverick,” I mean, there is a different kind of impact that comes with the experience of Cannes that I have not actually felt that much. I feel strongly about that. I think more and more we need that human connection, not just saying two minutes of some footage from a movie.

Cannes really presents a springboard for films that I don’t think you can get if you invest the same amount of money in marketing. I must say, it’s important to have all this talent here, but I thought it was great to see Bob Iger and Tim Cook coming for the first time to Cannes. It’s this collective experience of living the moment of a movie that I find a pure theatrical release can never bring. But you have to come with the right movie. Timing and release schedules play a big role, but Scorsese is releasing in October. So if you have the right movie, the release date doesn’t have to matter.

Let’s talk about the Oscars. Fremaux has said that they should only award American films Best Picture. You were here in 2011 with “The Artist,” which was not an American production, and it went on to win Best Picture. Where do you fall on this debate?

I remember going to the Oscars when “The Artist” won five major Oscars, not Best International Feature Film. I was sitting there and there were such big U.S. filmmakers nominated for Best Director. When the presenter read the category, he had trouble reading “Michel Hazanavicius.” I thought, “Wow, it’s great that the Academy is capable of voting for someone they’ve never met and can’t even pronounce.” So I think Cannes and the Oscars should have no boundaries. I think the only boundaries should be talent. I don’t think geography should play a role. That’s really important in today’s role. “The Artist” — and “Parasite” — would never have had the life it had without Cannes. I lived it. “The Artist” would have been a small success for France without Cannes. Nobody else would’ve seen it.

In that case, you think the Best Picture race should start at Cannes?

I think it’s the right thing. A work of art should not be judged by countries and boundaries. The Oscars has such worldwide impact.

“The Idol” premiered at the festival this year. It’s not the first time TV has played at the festival, but more and more filmmakers are working in that medium. Will Cannes create more space for TV?

We already don’t have space! [laughs] No, right now, we have an unwritten policy that we bring from time to time TV from filmmakers who are right for Cannes. There’s nothing wrong with showcasing it sometimes, but movies have to remain clearly identifiable. If you try to be too many things for too many people, the message becomes complicated. At some point you have to make choices and you cannot be everywhere for everyone. This may evolve. We have to be open-minded about where the world is going at the moment. But as of today, I think it’s better to stay clear about who we are and not try to be too many things.

This festival is so hard to navigate. No matter who you are, you run into chaos on the streets, problems with access, constant crowds. What can you do to improve this?

It’s an ongoing conversation that we are having with the city of Cannes and the mayor because we don’t control these spaces. The city does. Obviously, for them, the festival is really important but you need to find the right solutions. You cannot decide to stop this year to find them because then we wouldn’t have a festival for five years. So you have to find ways to do it each year. I don’t have the answer, but I’m with you on this. We need to have more space. We have to find a smart solution that allows us to create that without impacting the ongoing festival. That’s the challenge.

There’s this push and pull that’s very complicated between ensuring security, which is an issue, because security is important but I know it can really be a burden for people who visit. It’s very difficult to find the right balance. This has been something I’ve been watching closely. We have to think about how we manage crowds better, maybe make it more fluid and professional, while being respectful of all the other things. It’s not a challenge, though. It’s an opportunity to create a better experience.

The festival circuit has gotten much more competitive in recent years. How do you see Cannes competing with other major European festivals?

I really don’t see us as competing with them. I really think that the big festivals — Berlin, Cannes, Venice, Toronto — they have their place, and they insert themselves well into the release patterns for movies. We all play the same important role. We should be there for cinema, giving visibility to smaller movies, which is even more important now because we live in a blockbuster world. I think it’s important that they co-exist. Everyone has their space. We should all be in this together for the greater good, which is cinema and bringing up the new generation.