To say anything in film history is a “first” can be a dubious claim. Not only is film complicated as a medium but so much of its history has been lost. Our picture of cinema is one largely of the movies that have been lucky enough to survive, or the movies that have been considered important or special enough to be preserved. It takes even more effort to find and preserve the history of filmmakers who existed outside the early film studios.

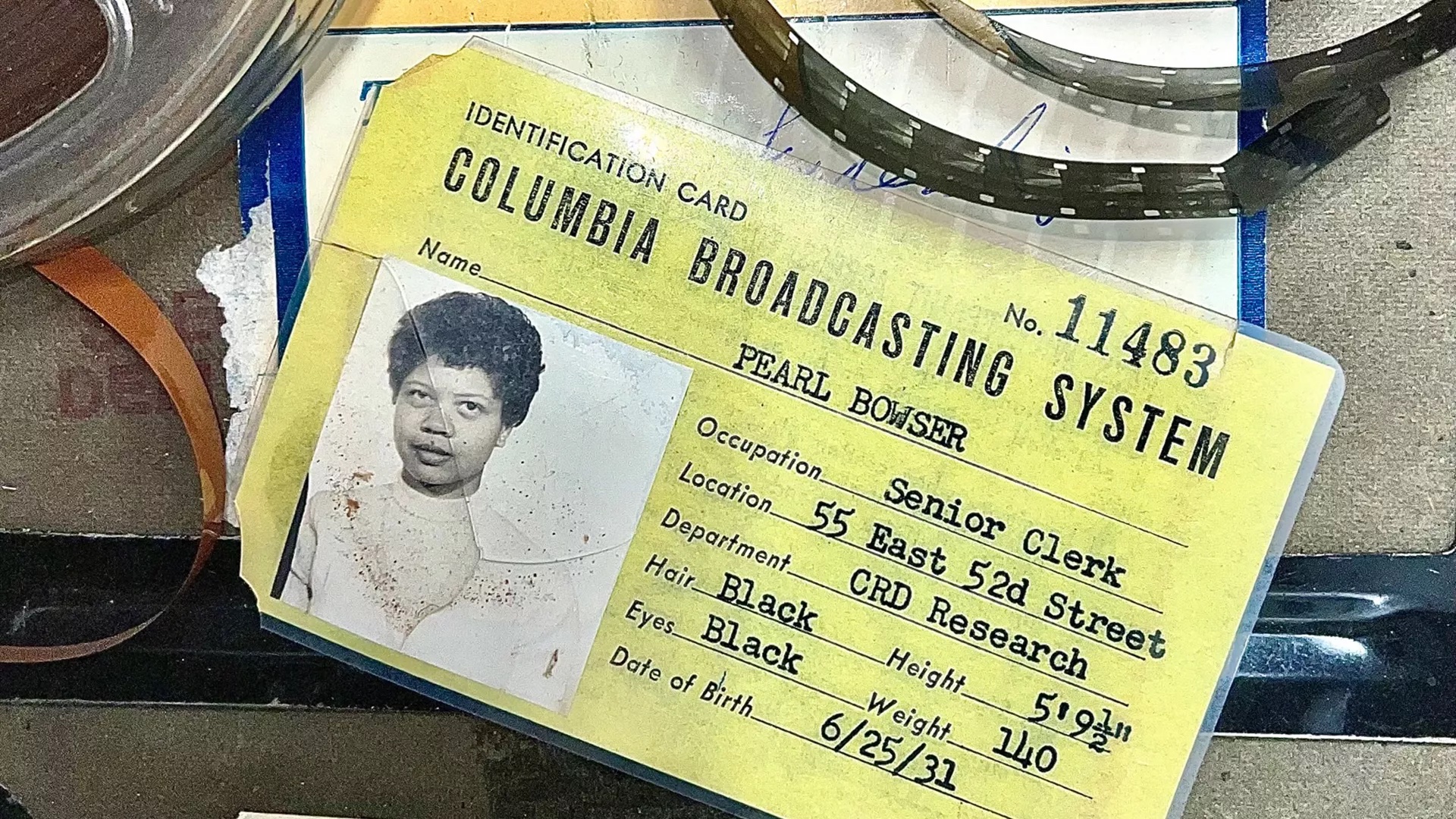

But that effort is exactly what film historian Pearl Bowser undertook, and she is now being honored for it with “The Boom Is Really An Echo: Selections from the Pearl Bowser Media Collection” at BAM.

Bowser’s probably best known as the scholar who revived interest in director Oscar Micheaux and the early days of Black cinema in the ‘70s — an interest that abides to this day with a Micheaux series launching at Film Forum on May 3. But her work was just as much about the present as the past, and still is.

Finding, preserving, and championing early Black cinema helped connect Black filmmakers in the ‘70s to the heart of film history. It’s why Howser’s landmark 1973 essay is called “History Lesson: Why The Boom Is Really An Echo,” giving the flourishing Black artists the thing white artists always have by default: roots and the sense of continuing or innovating on a legacy.

The importance of simply showing what’s out there is something that wasn’t lost on BAM President Gina Duncan when she took over the film program in 2017 and saw a reflection of the power of Bowser’s work.

“I noticed that when I would talk to my friends outside of the film industry, they’d hear about ‘Oscars So White’ and often say, ‘Well, the problem is we’ve got to get more people of color making films. And we all have to go out and buy tickets and support these films. That’s the only way they’re going to give us more opportunities.’ There’s an element of truth within that, but one of the things I thought folks were missing was this understanding that Black people, women, people of all backgrounds, have been making films and contributing to the form since the very beginning.”

When Duncan began a repertory program that reflected the true diversity of films, she found that BAM didn’t have to bend over backwards to bring in more diverse and younger audiences to all their films. “It’s not that people aren’t getting in. It’s that they’re not able to stay in — and what do we need to do to help people stay in the industry and continue to make work and get that work into the spaces it’s meant for?” Duncan said.

Part of that effort has to be making space for the history we have, and a significant portion of that is down to Bowser’s research. BAM’s retrospective “The Boom Is Really An Echo: Selections from the Pearl Bowser Media Collection” shines a lot on all the facets of that work, curated with the help of Bowser’s daughter Gillian and the National Museum of African American History and Culture, from her own filmmaking to her cookbook to her work on the films of Oscar Micheaux.

The retrospective is a timely reminder that film history is never locked in place. “I really love that we’re doing this now as another moment to celebrate all that [Bowser] contributed to Brooklyn and film in her 90 years,” Duncan said.

“The Boom Is Really An Echo: Selections from the Pearl Bowser Media Collection” ends April 21 at BAM.