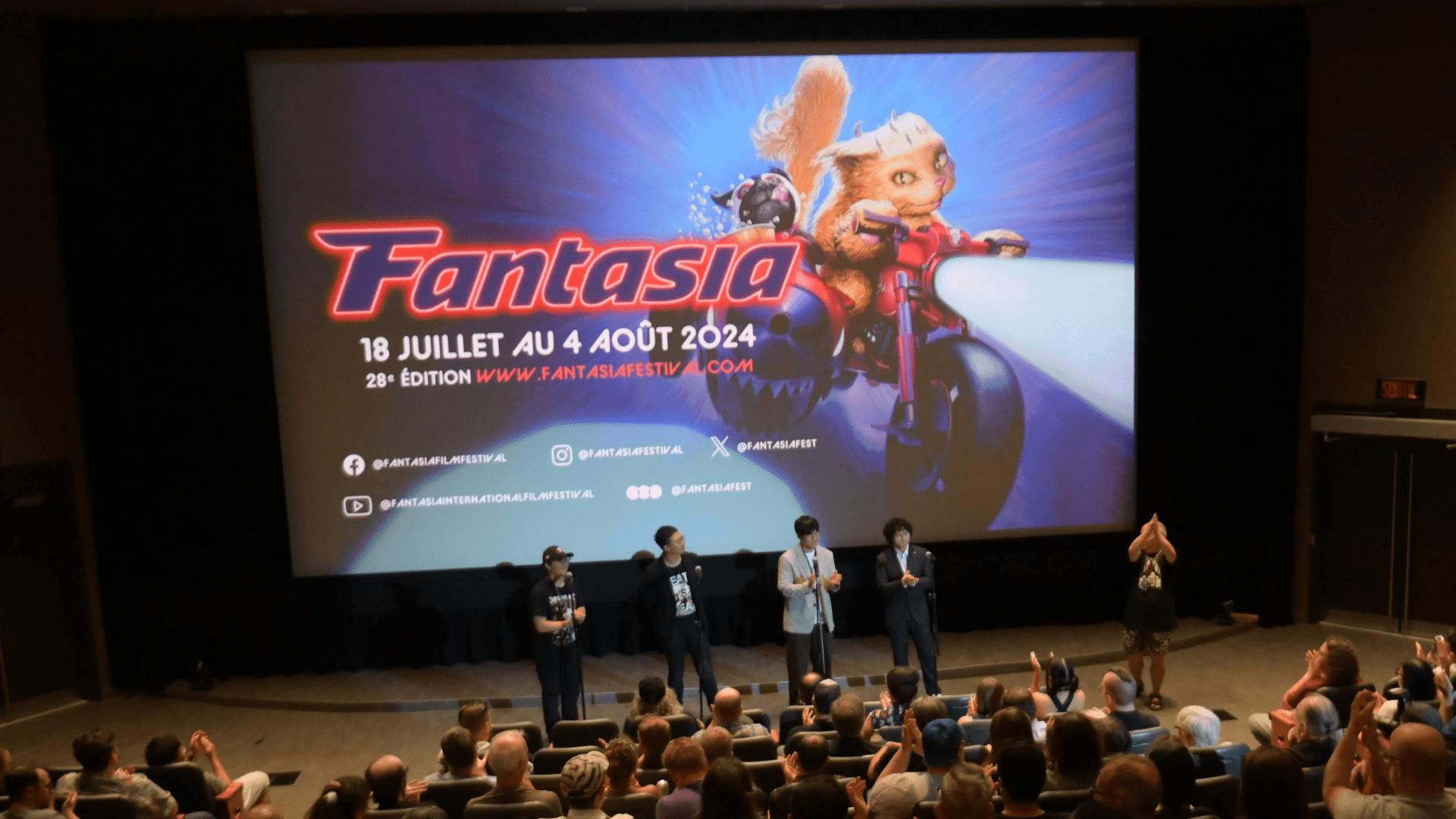

Only at Fantasia Fest could you confuse the sound of a movie premiere for feeding time at the local cat cafe. As attendees continue to cycle through the latest edition of Montreal’s historic three-week genre event (held this year from July 18 to August 4), the time-honored tradition of audience callbacks once again has guests meowing at the screen.

Yes. Meowing. At the screen.

“It’s something that I always have to remember to warn new filmmakers about because they’re so excited to see a big room, but when they hear that meowing, it terrifies them,” co-festival director Mitch Davis told IndieWire. “It implies that the audience maybe doesn’t have much of an attention span. The film hasn’t even begun yet, and the crowd is making noise. But the actual experience of watching a movie with them is the complete opposite.”

Other film festivals have similar traditions. At Cannes, someone in the audience will always shout “Raoul!” before showings at the Debussy Theater. At TIFF, people “Aaaarrgh!” like pirates whenever they see an anti-piracy notice. Call-and-response rituals often reflect the movie cycles they come from, but the reason behind the meowing at Fantasia tells the bigger story of a passionate film community finding, honing, and caring for its niche.

Founded in 1996, the largest and longest-running genre event in North America is kept alive by its audience — an effervescent puddle of eclectic French-Canadians and visitors who, whether they know it or not, are born out of a local blind spot from nearly 30 years ago. The Hong Kong New Wave, then spotlighting contemporary talents like Ringo Lam and John Woo, reached Canada way before the mid-nineties. But until the advent of Fantasia, many of these titles failed to show in Montreal for reasons organizers still can’t explain.

“These films were having an enormous culture-shifting export all over the world and building fanbases comprised of people who had never before followed Hong Kong cinema,” said Davis. “And yet in Montreal, there was this bizarre gap amidst the smaller festivals that existed at the time. These films were being shown at Vancouver International Film Festival. They were being shown at TIFF, which at that time was still called the Festival of Festivals. Canada had multiple great outlets for these films, but Montreal consistently had none.”

Photo credit: Julie Delisle, Fantasia International Film Festival

Hardcore film aficionados, like Davis, connected instead over rumored successes via Usenet (a vestige of the pre-social media age) and if they were lucky, sometimes caught a rare showing on laserdisc in Montreal’s Chinatown, critically without subtitles. Festival president Pierre Corbeil, who still leads the event today, knew there was a need to serve a hidden audience — but he couldn’t have predicted how big that need would be.

With the help of Martin Sauvageau and André Dubois, Corbeil used money from his post-production company to bankroll a month’s worth of double features at Imperial Cinema that summer. A burlesque theater from 1918, the venue was intended to house a “single one-month blowout of all the great Hong Kong films from the last four years,” but would become home to an annual event of almost mythic proportions.

“He wasn’t sure how many people would come, but he wanted to see these films on a big screen with his friends and he wanted to turn more people onto them,” said Davis. “But somehow from the opening night — it was a Jet Li film, ‘My Father Is a Hero’ — there was a line around the block. It actually sold out all 940 tickets, which is completely against all reason. It’s a miracle that happened.”

Photo credit: Julie Delisle, Fantasia International Film Festival

The frenzy continued in the weeks that followed with smaller films, like “Prison on Fire” and “Green Snake,” selling out night after night.

“I didn’t know five people in my personal life that I could discuss these films with usually,” said Davis, who remembers seeing hidden gems only ever talked about in the periphery “becoming almost like Star Wars.”

Then known as Fan + Asia, and at another time as Fan / Asia, the niche event morphed to accommodate its mammoth draw. The next year, Davis and his then-roommate Karim Husain (a cinematographer best known for his work with Brandon Cronenberg on “Infinity Pool” and “Possessor”) used their status as genre superfans to become programmers for the festival’s international side.

“In Fantasia parlance back then that meant anything that wasn’t Asian,” said Davis, laughing and noting that the definition has changed since.

Expanding the festival’s scope allowed Fantasia to more thoroughly explore genre — incorporating horror, sci-fi, and fantasy from other countries as well as documentaries, arthouse, and more. Pulling back its duration to three weeks instead of four (“We were enthusiastic, but our staff was crawling by the end,” Davis said), the festival became a buzzy destination for cinephiles to connect through films that both defy and celebrate categorization. The meowing is Fantasia loudly honoring that audience.

Photo credit: Julie Delisle, Fantasia International Film Festival

Speaking with IndieWire at McKibbins Irish Pub (a beloved if vaguely off-theme haunt where attendees meet up most nights), former Fangoria editor-in-chief Michael Gingold shared the memories that taught him what this specific audience could be in its infancy.

“In the summer of 1999, Fantasia showed the movie ‘Stir of Echoes,’ a supernatural horror film by David Koepp starring Kevin Bacon as a guy who gets hypnotized at a party and he develops the ability to see ghosts,” said Gingold.

“I guess part of the condition with the distributor showing the film was that the trailer for ‘Stir of Echoes’ show before every single movie prior to its screening, which I believe was at the end of the festival. There’s a moment in the movie and in the trailer where Kevin Bacon’s character is at a party and they say, ‘Hey, who wants to be hypnotized?’ And Bacon puts on this kind of blue-collar accent and says, ‘Hey, do me!’ About a week into the festival, as soon as that trailer would come on, everyone in the audience would start yelling, ‘Do me!’”

Despite lasting just that one year, Gingold thinks of the “Stir of Echoes” fad as a predecessor to the meow, which wouldn’t emerge for more than a decade.

Fantasia audiences are remarkably uncynical, but they’re also more sophisticated than a two-syllable sex joke or meowing makes them sound. Hideo Nakata’s “Ringu,” a seemingly hokey supernatural horror film about a cursed video tape, screened at the festival the year before in 1998 and brought out something very different in its guests.

Per Gingold, “Nobody expected the moment with Sadako crawling out of screen, and when that happened, the temperature in the room dropped about 40 degrees. You could literally feel everybody shivering, seeing a movie that practically no one in North America had heard of two hours before.”

It was freezing, but also pin-drop silent — the entire theater stuck in a kind of petrified non-response as they collectively surrendered to the terror on screen.

“The story goes that afterward Fantasia had the print and they were within hours of shipping it back to Japan when they got a message saying, ‘We’re changing the destination,’” Gingold said. “’We need to send this over to Steven Spielberg‘s office at DreamWorks.’ Then we got ‘The Ring’ remake, and the rest is history.”

Photo credit: Julie Delisle, Fantasia International Film Festival

It’s that magical combination of total investment and witty irreverence (plus, a wide understanding that Montreal residents are generally awesome) that makes Fantasia crowds so intoxicating to this day. The “festival bubble” — a term used to describe the sometimes-inflated scores critics give to movies premiered at events where they had a good time — exists everywhere. But even that potential bias can be a point of pride for organizers who have spent years putting their audiences first.

“Some of the films you see at Fantasia are better at Fantasia because of the audience,” said director of partnerships Marc Lamothe, who also stopped by McKibbins. “When you are there, you feel like it is the best film in the world. Then, you watch it on your own and you say, ‘What happened?’ You see that film again without this audience and it’s not even the same film.”

There’s an innate joy to supporting new creators that is especially palpable at Fantasia (“I feel like our audience is very much aware that they’re part of a filmmaker’s story and they’re very proud to be a part of it,” said Davis) — but that audience isn’t built on goodwill alone. Over the years, festival organizers have made a handful of key logistical choices that have helped prioritize the enjoyment of the crowd over the agenda of the industry.

Photo credit: Julie Delisle, Fantasia International Film Festival

Because of its extended schedule, Fantasia screenings rarely if ever happen in the morning. Films are instead shown during standard matinees times or slotted into a rigorously finessed evening schedule with limited overlap. Partnering with Concordia University — which will house the festival through 2030 thanks to a newly inked contract — Fantasia screens out of just two theaters: the Sir George Williams University Alumni Auditorium (colloquially known as “The Hall”) and the J.A. DeSève Cinema. Compare that to something like Sundance, which even cutting back this year used at least eight venues over ten days, and the difference is stark.

“By doing it like this, it’s much more difficult for the industry to cover it,” said Davis. “That’s certainly the case and it’s unfortunate, but the idea is that by only having two films at the same time, everything has a real chance of finding its audience. And there won’t be a situation where one really popular film that already has all the preexisting awareness in the world shows up and just demolishes everything else in its screening slot.”

It’s from within that breathing room the meow finally emerged.

In 2012, Fantasia put on a history-making edition of DJ XL5’s Zappin’ Party — a regular programming block combining short films with old TV ads to give audiences the feel of “zapping” through channels — as presented by Lamothe. Even then, the festival organizer was curating with original Betamax tapes, which provide only one hour of storage. A two-hour program mandated he switch tapes halfway through, leaving roughly 30 seconds of dead air in the theater.

“The last thing they had seen in 2012 before that break was a short from Simon’s Cat called ‘Cat Man Do,’” said Lamothe. “When you leave 800 people in the dark, they will do something. That’s what Fantasia is. But because they had just seen that cat go meow, they meowed.”

For the first few years, the cat-calling remained mostly exclusive to Zappin’ as a kind of “inside joke” for repeat attendees, Lamothe said. He isn’t sure when or how the idea reached the rest of the festival, but any schedule designed for genre exploration also encourages cross-pollination. These days every Fantasia screening begins with a cacophony of meows — timed by the audience to start and stop at black leader. (If you’re not a projectionist, that’s the blank screen that divides ads and trailers from the rest of your feature presentation.)

“What’s beautiful about Fantasia is that we never groomed the people to do that. They do that on their own,” Lamothe said, noting the variety of other animal noises that have emerged over time. “Of course we program wonderful films, but the audience is the core of the experience. They meow, yes, but when they meow, sometimes there’s also a dog in front or there’s a sheep in the back. There’s fun everywhere.”

Meowing gives every guest, industry and non-industry, an opportunity to perform — a fact plainly reflected in the orange cat mascot now proudly adorning most of the festival’s promotional materials — but it’s not their only chance to participate. Almost a decade ago, an indescribable but unusual commercial for Nongshim instant noodles developed a Fantasia cult following. Audiences whoop and holler for the ad’s duration and guests are often given free samples by the baffled sponsor as they exit the theater.

“People go crazy for Nongshim,” said Lamothe. “Why? I still don’t know. And that’s me programming that commercial for nine years in a row. Even Nongshim is telling me, ‘You don’t have to play that anymore, it’s an old ad!’ And I say, ‘No, you don’t understand. This is part of the DNA of the festival.’”

“There was even one year they gave us a more conventional ad and the audience was bummed out by it,” said Davis. “I have no explanation.”

Photo credit: Julie Delisle, Fantasia International Film Festival

Confusion giving way to amused acceptance is a theme across Fantasia, and yes, one worth gently reminding filmmakers about if they’re ever invited to entertain its fans. Asked about the most memorable reaction to the meowing he has witnessed, Davis recalled presenting the 1996 erotic drama “Szamanka” with its director, the late Polish filmmaker Andrzej Żuławski.

“There’s a huge audience there. Żuławski was smiling, he was so happy, and as we got off the stage, he leaned over to me and said, ‘This is just fantastic. So fantastic!’ It was going to be this rapturous screening and then, of course, the lights go out and the meowing begins,” Davis said. “I looked up at Andrzej, and his face dropped into a different time zone. He really looked disturbed and I don’t blame him.”

When the credits rolled, Żuławski was back at ease and the audience burst with questions.

“It’s just such a generous, beautiful crowd and they’re really nurturing,” Davis said. “What I love is that if a screening goes well, the filmmaker comes back with completely different body language for the Q&A, and their voice has changed. You feel that their lives have changed in real time with the audience and, to some extent, that the audience is aware of that and enjoys it as much as we do.”

More than 125 features and over 200 shorts make up this year’s Fantasia Fest lineup. And while it may be the movies and artists bringing these audiences together, it’s the more than 100,000 festival-goers returning annually since 2016 that Davis, Lamothe, and their fellow Canadian cinephiles are most dedicated to protecting.

“A lot of old school returners who haven’t been here for even 15 years come back and they tell me when they close their eyes in the theater, it feels like they’re with the same people from the nineties and then they open their eyes and see all these twenty-somethings,” said Davis. “It’s a surreal thing because everything has changed in so many meaningful ways and yet the audience feels so much like the same audience in the first generation.”

Only now… they meow.